VANCOUVER, British Columbia—Former Olympic athletes, international humanitarian leaders, and the private sector have come to the Vancouver games in full support of Right To Play, an nongovernmental organization (NGO) with a mission to teach life skills to children in disadvantaged countries by engaging them through sport.

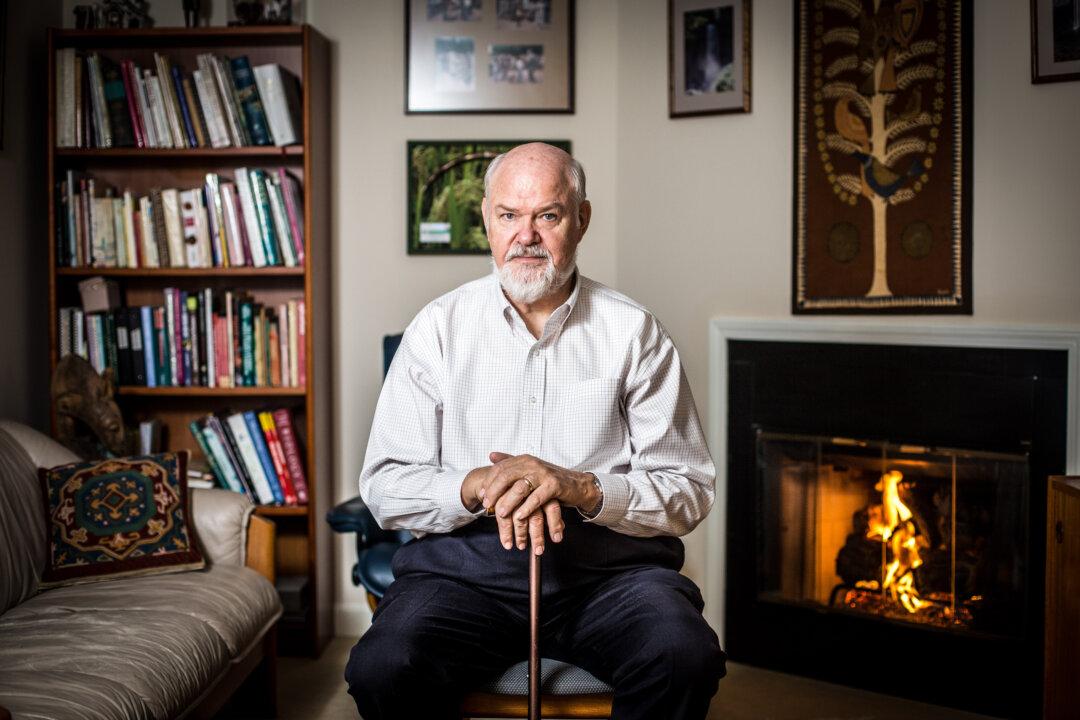

Shortly after moving to Canada in 2000, former Norwegian four-time gold Olympic medalist Johann Olav Koss founded Right To Play with the express purpose of teaching children through play.

Right To Play’s temporary home during the Olympics is in a pavilion called World Of Play at Concord Place in Vancouver’s False Creek waterfront area. Pictorial displays, multimedia, and a games room for kids educate 10,000 visitors a day about Right To Play’s work in 23 countries.

“It’s been a great way to kind of achieve things,” says Koss.

Headquartered in Toronto, Right To Play has more than 350 athlete-ambassadors from 40 countries, some of whom have been busy during Vancouver 2010 engaging and inspiring school children in Surrey as part of a partnership with Surrey city government.

Right To Play, previously called Olympic Aid, is a legacy of the organizing committee of the 1994 Lillehammer games. Koss was lead ambassador back then when he donated his medal winnings and challenged fellow athletes and the public to contribute.

An unprecedented $18 million was raised, which was used to support developmental aid projects in Sarajevo, Eritrea, Guatemala, Afghanistan, and Lebanon.

“That was an amazing, life-changing experience for me, and after the games I was then off to continue the legacy of Olympic Aid to other, future games,” says Koss.

Olympic Aid thrived, generating large donations for international aid. At the 1996 Atlanta games, a partnership with UNICEF raised $13 million, and vaccination programs for 12.2 million children and over 800,000 women in 10 countries were carried out as a result.

“Originally the Olympic Games was only kind of an income generator, like a fundraising mechanism,” Koss says. “It was really natural to what I believe in, and then we started Right To Play.”

The concept of play as a human right is gaining tremendous credibility in humanitarian circles. At the Salt Lake City Olympics in 2002, a round-table discussion titled “Healthier, Safer, Stronger: Using sport for development to build a brighter future for children worldwide,” had United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan giving the keynote address.

For the Vancouver Olympics, the University of British Columbia put together a five-part dialogue series highlighting sport and development. Speaking on Feb. 17, well-known activist Stephen Lewis noted that “every single country on the face of the earth, save two, have ratified a convention, which elevates the right to play to a human right. It is not merely a phrase. It is a human right.”

Right To Play ambassador Daniel Igali, who won gold for Canada in the men’s freestyle wrestling at the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, Australia, got involved because he wanted to make a difference.

“Right To Play isn’t about giving red balls to kids so they can just run around. Right To Play essentially empowers kids, makes them understand the power they have within, gives them life skills, gives them deductive skills, makes them forget about where they are and focus on what they can be … Right To Play does that consistently,” he says.

Fundamental to the organization’s success is a commitment beyond aid dollars to the training of volunteers to mentor children according to the organization’s curriculum and philosophies.

“What we’re doing is going into the community and training individuals to become coaches and teachers in the games and in the sports programs,” says Koss. “We have evaluation and constant retraining and updates and make sure that every coach has a protective role over the child, so they understand about child protective issues, and respect for one another, and the values we believe in.”

The positive effects of Right To Play’s approach are extensive. United Nations reports have acknowledged the organization’s success in war torn countries in limiting the numbers of child soldiers recruited to rebel groups or military service from refugee camps.

“They are happier, they believe in coming back home, but changing the country to a peaceful country instead of a war country,” Koss says.

Shortly after moving to Canada in 2000, former Norwegian four-time gold Olympic medalist Johann Olav Koss founded Right To Play with the express purpose of teaching children through play.

Right To Play’s temporary home during the Olympics is in a pavilion called World Of Play at Concord Place in Vancouver’s False Creek waterfront area. Pictorial displays, multimedia, and a games room for kids educate 10,000 visitors a day about Right To Play’s work in 23 countries.

“It’s been a great way to kind of achieve things,” says Koss.

Headquartered in Toronto, Right To Play has more than 350 athlete-ambassadors from 40 countries, some of whom have been busy during Vancouver 2010 engaging and inspiring school children in Surrey as part of a partnership with Surrey city government.

Right To Play, previously called Olympic Aid, is a legacy of the organizing committee of the 1994 Lillehammer games. Koss was lead ambassador back then when he donated his medal winnings and challenged fellow athletes and the public to contribute.

An unprecedented $18 million was raised, which was used to support developmental aid projects in Sarajevo, Eritrea, Guatemala, Afghanistan, and Lebanon.

“That was an amazing, life-changing experience for me, and after the games I was then off to continue the legacy of Olympic Aid to other, future games,” says Koss.

Olympic Aid thrived, generating large donations for international aid. At the 1996 Atlanta games, a partnership with UNICEF raised $13 million, and vaccination programs for 12.2 million children and over 800,000 women in 10 countries were carried out as a result.

“Originally the Olympic Games was only kind of an income generator, like a fundraising mechanism,” Koss says. “It was really natural to what I believe in, and then we started Right To Play.”

The concept of play as a human right is gaining tremendous credibility in humanitarian circles. At the Salt Lake City Olympics in 2002, a round-table discussion titled “Healthier, Safer, Stronger: Using sport for development to build a brighter future for children worldwide,” had United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan giving the keynote address.

For the Vancouver Olympics, the University of British Columbia put together a five-part dialogue series highlighting sport and development. Speaking on Feb. 17, well-known activist Stephen Lewis noted that “every single country on the face of the earth, save two, have ratified a convention, which elevates the right to play to a human right. It is not merely a phrase. It is a human right.”

Right To Play ambassador Daniel Igali, who won gold for Canada in the men’s freestyle wrestling at the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, Australia, got involved because he wanted to make a difference.

“Right To Play isn’t about giving red balls to kids so they can just run around. Right To Play essentially empowers kids, makes them understand the power they have within, gives them life skills, gives them deductive skills, makes them forget about where they are and focus on what they can be … Right To Play does that consistently,” he says.

Fundamental to the organization’s success is a commitment beyond aid dollars to the training of volunteers to mentor children according to the organization’s curriculum and philosophies.

“What we’re doing is going into the community and training individuals to become coaches and teachers in the games and in the sports programs,” says Koss. “We have evaluation and constant retraining and updates and make sure that every coach has a protective role over the child, so they understand about child protective issues, and respect for one another, and the values we believe in.”

The positive effects of Right To Play’s approach are extensive. United Nations reports have acknowledged the organization’s success in war torn countries in limiting the numbers of child soldiers recruited to rebel groups or military service from refugee camps.

“They are happier, they believe in coming back home, but changing the country to a peaceful country instead of a war country,” Koss says.