“You are not a mother, you are a soldier!” I will never forget those words. That was in 2007, in Mosul, Iraq, my first of many deployments. I was a newly pinned staff sergeant (SSG) and for the first time in my adult life was in a place without my family for a very long time. I was a mother of four children, ranging from ages 3 to 17. I was in charge of the operating room (OR) section of my forward surgical team. We had been in Iraq for only two months when our detachment sergeant was sent to another location and in his place, we got a sergeant first class (SFC) from another unit who, from the get-go, seemed to have an issue with me. Those were his first words to me, standing in formation while introducing himself to the enlisted members of the team.

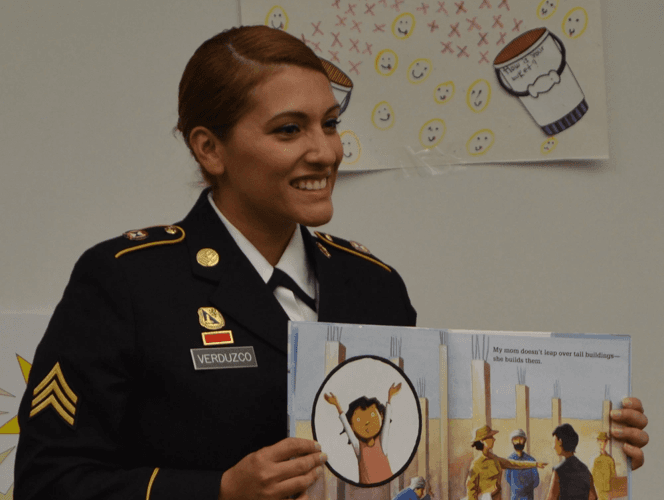

U.S. Army Reserve Sgt. Ana Verduzco with the 4th Sustainment Command (Expeditionary) reads "Hero Mom," by Melinda Hardin and Bryan Langdo, to children at Kinder Ranch Elementary, on Mar. 10, 2017. U.S. Army Reserve photo by Maj. Brandon R. Mace

Commentary

Mirna Velez De Mansilla served more than 20 years in the U.S. Army as a (68D) surgical technician in various clinical and operational assignments at Fort Bragg, N.C. as well as Landstuhl and Baumholder, Germany with three deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. She is the beloved mother of five children and lives in Texas with her loving husband. She also has the best adopted hermano anyone could ask for.