Shortly after being officially appointed leader of China, Xi Jinping started a campaign to rid the Chinese Communist Party of malfeasance. Officially, the aim was to end rampant corruption and bolster the Party’s ruling credentials; unofficially, Xi is seeking to dislodge a powerful political network controlled by his predecessor Jiang Zemin. Either way, the anti-corruption campaign, which has seen thousands of high- and low-ranking officials purged, has hung like a Damocles Sword over the Party’s mandate as rightful rulers of China.

Recently, however, the Party has decided to publicly discuss and allow uncensored citizen discussion of the question of its legitimacy.

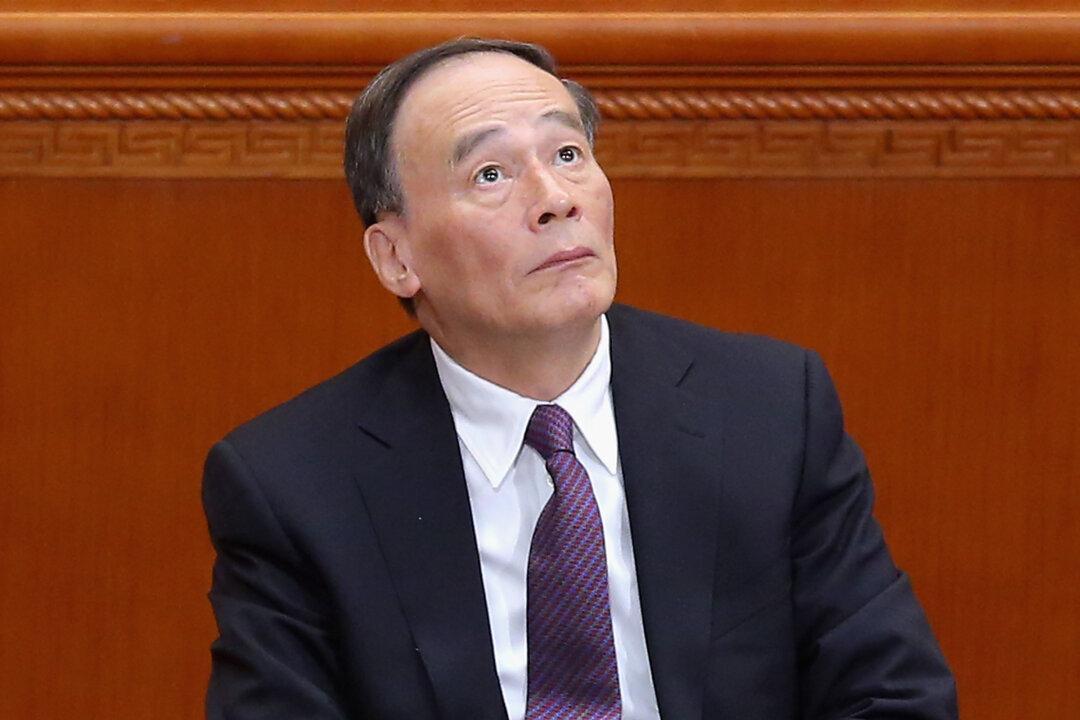

On Sept. 9, Wang Qishan, the head of the Party’s anti-corruption agency and de facto right-hand man to Xi Jinping, told over 60 former politicians and academics at a public meeting in Beijing that the “legitimacy of the ruling Party lies in history, its popular base and the mandate of the people,” according to the state-run Xinhua News Agency.

The Chinese social media was soon filled with talk about the Party’s claims to political legitimacy.

“Let’s have a referendum and let see the support percentage; such talk is merely self deception,” wrote a Chinese netizen from the city of Chenzhou in southern China on the popular microblogging service Sina Weibo. “Discussing the issue of legitimacy after 60 years of rule suggests a guilty conscience.”

Another comment was more forthcoming: “When did people ever vote?”

The following day, a WeChat account run by the state mouthpiece People’s Daily published an analysis of Wang’s remarks. It explained that with China rising to prominence on the world stage, there was a need to clarify the Party’s legitimacy to avoid “the Soviet Union’s tragedy.” The article, which was also carried by many state news outlets, said in conclusion that “to raise the question of the legitimacy of the ruling implies a deep sense of crisis.”

Why Now?

The Chinese communist regime has openly addressed its right to sit on the throne before, and by no coincidence, after tumultuous events that shake its political legitimacy.

For instance, after the Tiananmen Square massacre on June 4, then Party paramount leader Deng Xiaoping weaved through the message in his speech to military officers from the People’s Liberation Army that they could no longer rely on killing for legitimacy but rather on continued economic reform to win the support of the Chinese masses.

Analysts said that Xi Jinping’s China today faces pressing issues that once again calls the Party’s legitimacy into question.