Geography alone should make the Arab world Iran’s key foreign policy focus. Of Iran’s 13 immediate neighbors, seven are Arab countries.[1] But Tehran’s approach to the Arab world, with its 22 states extending from North Africa to the Arabian Peninsula, varies widely in intensity, and Iran’s objectives are equally varied depending on the country in question.

In other words, Iran does not have an “Arab policy” as such, but prefers a bilateral approach toward each Arab country. This reflects the fact that when leaders in Tehran ponder relations with the Arab states, they generally see a myriad of opportunities but also a number of challenges to Iranian interests.

This, however, is where consensus on the question of Iran’s relations with the Arab world ends. Debates within the Iranian state clearly show that the country’s leadership is deeply divided on the question of future relations with the Arab world. And Iran’s turbulent experience with the Arab revolutions since 2011—from the snub the Muslim Brothers in Egypt handed it to being compelled to side with Bashar al-Assad in Syria’s bloody civil war—has only exacerbated this policy contest in Tehran.

The Internal Struggle

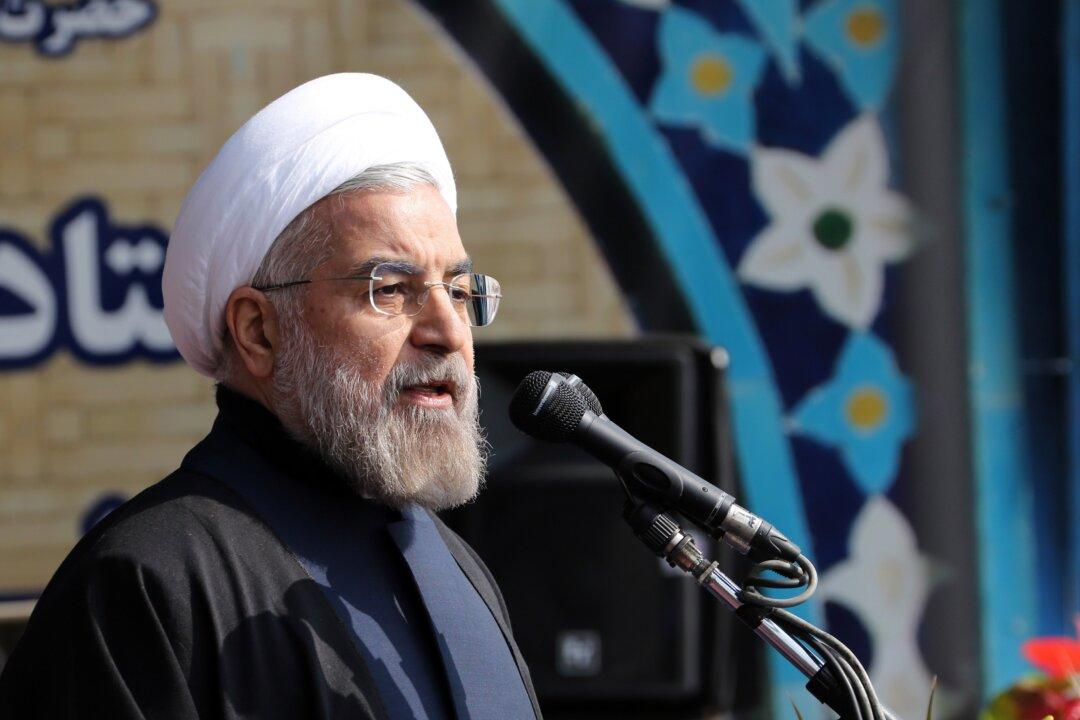

On one side are President Hassan Rouhani and his moderate faction, which have loudly called for a revamp of Iran’s approach to the Arab world. During Rouhani’s 2013 election campaign, one of his foreign policy pledges in which he mentioned a country by name was to mend broken relations with Saudi Arabia, Iran’s chief Arab rival.

Ayatollah Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, Rouhani’s long-time mentor and a regime patriarch, is the public face of this outreach to the Saudis. In early May, Rafsanjani told a visiting Italian parliamentary delegation, “Considering the regional and Islamic commonalities and the past practical experiences in thawing ties, [finding] the solution for the issues [that exist between] the two countries is very easy.”[2]

Such language is welcome news in Riyadh. As Abdul Rahman al-Rashed, a prominent Saudi commentator, put it, “Rafsanjani’s recommendation to reconcile with Saudi Arabia is a wise decision that will benefit everyone and end the misery of millions of Syrians, Lebanese, Yemenis, Afghans and others.” Al-Rashed was referring to the fact that in today’s greater Middle East, Tehran and Riyadh are engaged in numerous proxy wars, from Yemen to Syria and from Egypt to Pakistan. Cooler heads in both countries would admit that the blame for these Iranian-Saudi proxy wars is shared.

But as much as the Saudis long for Rafsanjani and his ilk to charter Tehran’s regional policies, they see that the root causes behind the Iran-Arab split lie elsewhere. Al-Rashed, stating a stance that is repeated frequently by other Gulf Arabs, put it this way: “Iran, today, is being ruled by the Revolutionary Guards, a paramilitary elite unit that has transformed from a force serving a theocratic authority to an army served by religious men.”[3]

This view of Iran’s internal political dynamics is somewhat oversimplified, but it still contains plenty of truth. When Gulf Arabs look at Iranian behavior, they see on the one hand the olive branch extended by the likes of Rouhani, Rafsanjani, or Foreign Minister Javad Zarif, who recently toured the Persian Gulf states and has been invited to visit Saudi Arabia. On the other hand, they witness the hawkish generals from the Revolutionary Guards who not only speak a language of coercion but who are clearly determined to expand Iran’s regional influence. The Gulf Arabs currently see this determination by Iran’s hardline ideologues in full force in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and elsewhere in the region.

An Important Nuance for the Arabs

Nonetheless, the fact that the Gulf Arabs are now once again willing to openly concede that competing narratives and worldviews exist in the ranks of the Tehran regime is in itself an important development.

Arab perceptions about Iranian intentions have in the last two decades played a paramount role in steering ties. In the mid-1990s, it was then President Rafsanjani’s much applauded outreach to Riyadh that successfully brought to an end the some 15 years of alienation between Iran and Saudi Arabia that had begun with Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Rafsanjani’s success was mainly due to his ability to change the perceptions of the Saudis and the other Gulf Arabs. Iranian foreign policy objectives at the time, such as a desire to re-integrate into the world economy and seek a détente with Washington after Iran’s isolation in the 1980s, intensified under Rafsanjani. For the Arabs, the significant moment came when Rafsanjani profoundly lessened the hostile revolutionary rhetoric that had so deeply unnerved Iran’s neighbors. The Arabs, in response, showed that they were not opposed to Iran returning from international isolation; they merely sought and obtained assurances from Tehran that the regime was serious in matching its rhetoric with action.

Furthermore, Rafsanjani cultivated personal ties with Arab leaders, particularly then Crown Prince Abdullah of Saudi Arabia. His guarantees quickly paid off, resulting in a rapid increase in trade and even closer Iranian-Saudi coordination of oil price policy within OPEC. He thus managed to rapidly reverse much of the bad blood that had existed. To this day, the Saudis consider the Rafsanjani period as the golden era in Saudi-Iranian relations.

This emphasis on shaping perceptions via personal diplomacy is particularly pertinent as Tehran looks again to allay Gulf Arab leaders’ fears. When the smaller Persian Gulf countries consider Iran, they are confronted with a giant of some 80 million people—over three times the size of the indigenous populations of the six GCC countries[4] combined—and when Tehran speaks, they listen warily. That Iran is today a nuclear threshold state only heightens Arab sensitivities.

If Rafsanjani (1989-1997) and his successor, Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005), understood the need to alleviate Arab anxieties, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-2013) and his original supporters in the Revolutionary Guards managed to squander the goodwill that had been generated in the preceding decade. The rabid Ahmadinejad epitomized the opposite of what the Gulf Arabs were hoping to hear from Tehran. At a time when the Gulf states asked for reassurance about Iran’s nuclear program, Ahmadinejad alarmed them more by claiming that “Iran’s nuclear program is a locomotive without brakes.”[5]

Can Rouhani Prevail?

Rouhani took over the presidency on a platform against such harmful rhetoric, and in his first year in office he has continued to confront the hawks in Tehran. Calling these figures “illiterates” who do not understand international politics and resort to empty but costly sloganeering, Rouhani seeks to revert to the Rafsanjani era and reassure Iran’s Gulf Arab neighbors.

For example, in December 2013, and only months into the Rouhani presidency, Iran removed a squadron of fighter jets from Abu Musa, an island in the Persian Gulf that is disputed by the United Arab Emirates. This gesture of de-escalation was mainly aimed at the United States, but the Gulf Arabs could not have failed to notice.

Nonetheless, Rouhani has an uphill battle in facing his hawkish critics. And much of his struggle to shape Iran’s approach to the region is unfolding in public view. In an unmistakable jab against the senior commanders of the Revolutionary Guards, Rouhani recently repeated his warning about empty but costly sloganeering. “It is very important to formulate one’s sentences and speeches in a way that is not construed as a threat, [as an] intention to strike a blow,” he said. As if scolding a group of adolescents, Rouhani lamented that “launching missiles and staging military exercises to scare off the other side is not good deterrence.”[6] In this intra-regime feud in Tehran, Rouhani claims an upper hand. “I have the support of the Supreme Leader,” he warned his critics.

So far, some of his key rivals are not yet ready to back off. Mohammad Ali Jafari, the head of the Revolutionary Guards, was equally candid. “Some,” he said, “do not show their true face [intentions].”[7] This is now a fairly common accusation leveled against the Rouhani administration, with the implication that its motives in regard to domestic and foreign policy are different than those it publicly proclaims, namely that its ultimate goal is to weaken the Islamic and revolutionary nature of the regime. Unlike Rouhani, Jafari and the other hawks see Iran as ascendant in the region, and argue that if anyone must change, it is Iran’s Arab rivals.

The outcome of this intra-regime rivalry in Tehran is far from clear. Much depends on how receptive the world and Iran’s neighbors are to Rouhani’s promise of a newly moderate Iran. An outright rejection of Rouhani can only embolden the alternative hawkish narrative and worldview.

The Gulf Arabs have clearly identified this dichotomy in the Iranian regime, and some have chosen to be hopeful and to bet that the Rouhani faction will prevail. A good example of this is Oman’s approach toward Iran, including Rouhani’s March visit to Muscat and the signing of a multibillion dollar natural gas deal.

Others, particularly the Saudis, though they wish it were otherwise, believe that the revolutionary hawks are more likely to steer an interventionist policy toward the Arab world. While many Saudi reservations are legitimate, there is a danger of setting in motion a self-fulfilling prophesy about the trajectory of Iran’s Arab policies. Anti-Iran measures by Riyadh, particularly those enveloped in a sectarian and anti-Shi‘i platform, can only undercut Rouhani’s standing in Tehran and hence his regional outreach. However, at this time even the Saudis are signaling some hope that the Rouhani side might succeed, having recently extended an invitation to Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif to visit the Kingdom.

By emphasizing the existence of moderate Iranian voices, the Gulf Arabs can not only hope for but in fact help empower those in Tehran who are yearning to turn the page on Iran’s turbulent relations with its Gulf Arab neighbors.

____________________

Notes:

[1] These are Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and Oman.

[2] “Iran-Saudi Issues Can be Solved Very Easily - Top Cleric,” Press TV, 6 May 2014.

[3] “Iran Must Heed Rafsanjani’s Advice,” Arab News, 2 May 2014.

[4] The GCC is composed of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

[5] “Ahmadinejad Compares Iran’s Nuclear Program to Train with ‘No Brakes,’” Radio Free Europe, 25 February 2007.

[6] “Rouhani Tells Iran Generals to Cut Hostile Rhetoric,” Reuters, 1 March 2014.

[7] Akbar Ganji, “Khamenei is Pessimistic about Nuclear Negotiations,” Huffington Post, 22 February 2014.

____________________

Alex Vatanka is a scholar at the Middle East Institute and a senior fellow at the US Air Force Special Operations School. This article was originally published at the Middle East Institute.