This week’s visit to Tehran by the Kuwaiti emir, Sheik Sabah al-Ahmad al-Sabah, is about more than Iranian-Kuwaiti relations. It might even be a pivotal moment in the shaping of Iran’s ties with the Arab countries across the Gulf. Kuwait, which currently holds the rotating presidency of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), is acting as a conduit for the collective unease that the GCC’s six member states, particularly Saudi Arabia, have about Iran’s regional policies. Saudi Arabia stands out both for the intensity of its fears about Iran, but also because its size and resources make it the Islamic Republic’s largest Arab rival. Sheik Sabah, who is trusted as an interlocutor by the Saudis, is expected to convey Riyadh’s anxieties to the Iranians—but will anyone in Tehran listen?

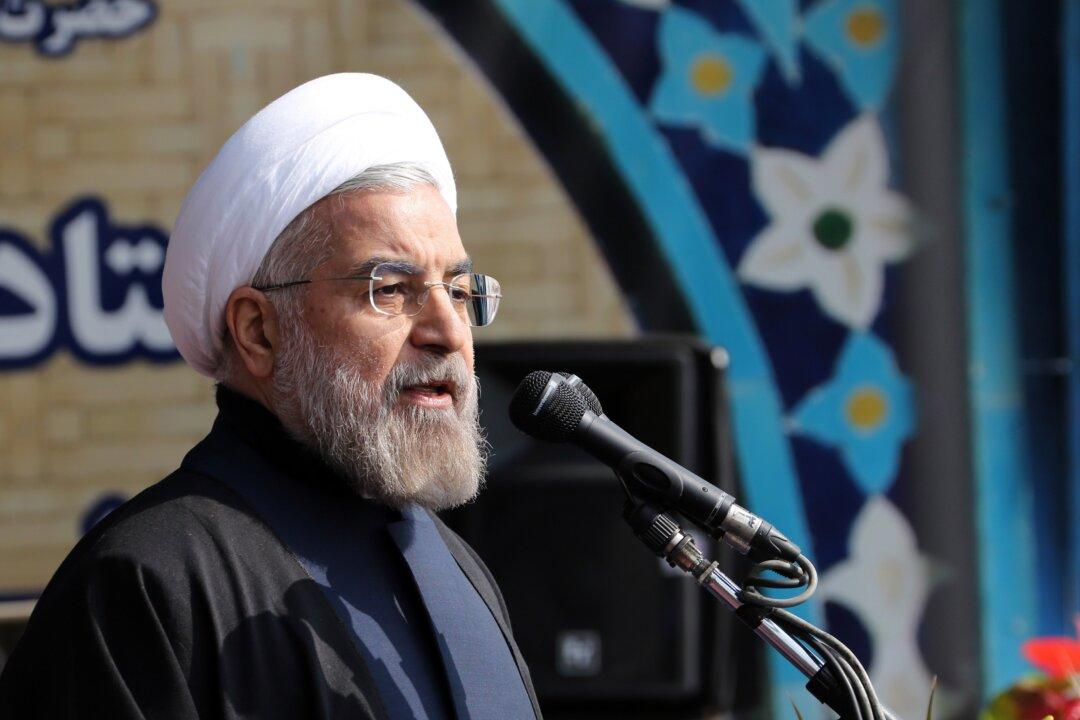

Rouhani and Riyadh

On April 29, 2014, Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani said during a live televised interview that his government is committed to pursuing a policy of détente toward Saudi Arabia. In the same interview, however, Rouhani used language that could be interpreted as extending only a conditional olive branch. The détente, he said, will be determined by Riyadh’s regional policy preferences.

“There is no obstacle from our side,” he said. “We hope that [the Saudis] understand the [changing] circumstances of the region…and [decide] that peace, brotherhood, security, and forcing terrorists out [of the region] is the best solution. God willing, if they come to this conclusion, we will not have any problems in relations with them.”[1]

Those skeptical of Rouhani’s intentions toward Riyadh will point to these sentences as an Iranian call for Saudi Arabia to accept that the security and political trends in today’s Middle East favor Iran and that the Saudis should adapt their policies to this reality. These skeptics will argue that Rouhani coming to power has not altered Tehran’s basic regional ambitions, and that Iran continues to pursue a zero-sum game against the Saudis.

If Riyadh reads Rouhani’s statement in this way, the implications are that Tehran simply expects the Saudis to stop backing the Syrian opposition; to embrace Iraq’s Shi‘a-dominated government; to formally invite Iran to the negotiating table to find resolutions to the stubborn political crises in Bahrain and Yemen; and, above all, to cease all opposition to Tehran’s nuclear program.

But Rouhani knows better than to expect sweeping Saudi submission to Tehran’s regional ambitions. Nothing he has done in relation to Saudi Arabia since he captured the presidency in August 2013 suggests him having such illusions. While his olive branch to Riyadh is conditional, he is surely aware that a successful détente requires a mutual process of give and take. The test for Rouhani is thus not Riyadh’s acquiescence, but whether he can meet the Saudis halfway. This requires him to first win the domestic argument for launching a policy of reconciliation toward Saudi Arabia. Not everyone in Tehran is sold on this idea.

Iranian Hard-liners and the Saudis

Inside Iran’s tangled domestic power play, there are those who still view enmity toward the House of Saud as a noble pillar of the Islamic Republic. These hard-liners consider Riyadh a pawn in the hands of the United States,[2] but also harbor deep resentment due to their perception of Riyadh as a proponent of anti-Shi‘i policies in the region, be it in Lebanon, Iraq, Bahrain, or elsewhere.

A ranking conservative member of Iran’s parliament recently urged Riyadh to “drop its support for takfiri terrorists” if it is serious about a détente.[3] The Iranian state uses the term “takfiri” against Sunnis who deem all other Muslim sects to be apostate. It is also code for Gulf Arab support for radical Sunni groups in the region. Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, is a frequent critic of the role that Gulf Arab states play in sustaining such groups, and this week he urged Sheik Sabah to pass along a message to his fellow Gulf Arab leaders to rethink such support because, he said, “these groups will [eventually] turn against their supporters.”[4] The Saudis, of course, counter that Iran needs to drop its support for its own radical Shi‘i groups, such as Hezbollah in Lebanon and various armed Shi‘i organizations in Iraq, as well as for Assad’s brutal repression in Syria.

The Iranian voices suspicious of the Saudis are often loud, mainly thanks to the access they enjoy to Iran’s state-funded media. But Iran’s Saudiphobes are increasingly being called to defend the merits of regional proxy conflicts with Saudi Arabia. As their critics point out, proxy conflicts, from Lebanon to Iraq to Bahrain to Syria, come at both high financial and political costs for Tehran. If left unchecked, the Iranian-Saudi/Shi‘i-Sunni rivalry can potentially bankrupt the Islamic Republic economically but also ideologically. Some among the ruling elite in Tehran are aware of the perils of Iran becoming an entrenched Shi‘i power in an Islamic world in which the Shi‘a are a minority and the Islamic Republic’s Islamist credentials are dwindling.

The Path Ahead

Given such realities, the faction around Rouhani is arguing for a reset. But this faction has yet to clearly articulate what such a reset would look like. This failure is mostly due to the internal power struggle in the Iranian regime. Since the Saudi question in Tehran is still a sensitive one, even Rouhani’s supporters do not openly argue for a policy reboot. They do not want to give ammunition to their hard-line critics by appearing soft on the Saudi question. Instead, their strategy is to point to recent Saudi decisions as offers of peace.

Iranian news sites close to Rouhani have been highlighting these Saudi decisions in recent months. Among them is King Abdullah’s decision to replace Prince Bandar bin Sultan, a man seen in Tehran as having a congenital aversion to Iran. Prince Bandar recently held the post of Saudi intelligence chief, and was tasked with bringing about the downfall of the Assad regime. Bandar’s removal was widely reported in Iran as a sign that Riyadh is coming around to the idea of a compromise with Iran over the future of Syria. Other recent decisions have included Saudi Foreign Minister Saud al-Faisal’s invitation to his Iranian counterpart, Javad Zarif, to attend an Islamic summit in Jeddah this month. Because Faisal is seen by Tehran as a hawk on the question of Iran, his invitation to Zarif was unexpected but welcomed.

In addition, the Iranian press has been portraying the arrival in Tehran of a new Saudi ambassador, Abdul Rahman al-Shehri, as a positive development. As Rouhani News put it, al-Shehri has met the “right people”—Rouhani’s supporters—and apparently sent positive reports to Riyadh that have begun to reshape Saudi thinking about the Islamic Republic.[5]

Another recent Saudi decision that Tehran has interpreted as a positive sign is Riyadh’s blacklisting of the anti-Shi‘a, al-Qa‘ida-linked al-Nusra Front and the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) as terrorist organizations. The fact that the Saudis had domestic reasons to blacklist the groups was of secondary importance to those in Tehran yearning for a new era in Iranian-Saudi relations. Also, Riyadh’s decision not to blacklist Hezbollah and other regional Shi‘i militant groups found in Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere could only have been encouraging from Tehran’s perspective. There are, after all, two sides to the sectarian conflict in the Middle East, and Tehran’s continued backing of regional Shi‘i militants is indisputable. Whether Rouhani can make concessions on this front is uncertain. Iran’s support for these militants is in the hands of the Revolutionary Guards and its external operations arm, the shadowy Quds Force. This branch of the Iranian regime is not answerable to Rouhani and his moderate allies, though nor is it immune to domestic and external pressures.

There are elements in both Tehran and Riyadh that admit to the dangers of an unchecked Shi‘i-Sunni conflict in the region. Hard-liners on both sides who are still driven by a sectarian mindset will need to be confronted, and it will not be easy. In the last decade, sectarianism has become the most potent vehicle for both Iran and Saudi Arabia to expand their regional influence. To address this reality and to stop pretending that the Shi‘i-Sunni conflict is instigated by Western powers—as Iranian leaders have often claimed—will amount to a promising departure from the past.[6]

Next Steps

Rouhani can hope that his case for a détente with Saudi Arabia will gain traction in Tehran. To be sure, this question remains highly sensitive in Iran—a result of Riyadh’s historic challenge to the Islamic Republic both as a geopolitical rival and a contender for the mantle of leadership in the Islamic world. But the Iranian president and his supporters can no doubt do more to propel the process of a détente.

Rouhani’s Saudi predicament in Tehran is about protecting his political capital. He cannot afford to be seen as soft on Riyadh, particularly not while he is simultaneously pursuing the equally sensitive but more pressing process of a détente with the United States, which is likewise questioned by hard-liners. Shortly after he came to office, Rouhani declined a Saudi invitation to visit the Kingdom. His supporters let it be known that he could not go to Riyadh unless the blueprint of a deal was in the making. Otherwise, they said, a state visit amounted to a win for the Saudis. Such is the ungenerous state of affairs vis-à-vis Tehran-Riyadh ties.

To move beyond the rhetoric of a détente, Rouhani needs to start formulating specific policy proposals for his Saudi agenda, which the Saudis have said that they want to hear. Rouhani also needs to do more to curry public opinion on this critical issue by emphasizing the dangers of remaining attached to a sectarian, zero-sum game mentality of rivalry with the Saudis. Most importantly, he needs to convince Khamenei and his foot soldiers in the Revolutionary Guards and Quds Force that compromises with the Saudis over key policy differences, with Syria, Iraq, Bahrain, and Yemen being the most obvious and pressing ones, are possible despite the fact that on the face of it they are intractable disagreements.

Decisions made by Riyadh can help or hinder Rouhani’s Saudi agenda, and at the moment they seem to augment the Iranian president’s hand. As for Riyadh, it does not want to be blindsided by Rouhani’s global charm offensive and a potential U.S.-Iranian nuclear deal. The Saudis are therefore preparing for all eventualities. At a minimum, Riyadh does not want to publicly appear as the spoiler as Iran and Saudi Arabia navigate through this arduous stage of bilateral relations; hence the repeated Saudi invitations to Iranian officials over the last few months.

Sheik Sabah let it be known this week that he brought with him a message from the Saudis. Time will tell what that message is and whether the fragmented Iranian leadership can agree on a positive response.

____________________

Notes:

[1] Islamic Republic Channel 1, 29 April 2014, transcript available through BBC Monitoring Service.

[2] “Al Saud Plays to Destabilize Lebanon and Forwards Its Agenda in the Levant,” Fars News Agency, 29 May 2014.

[3] “MP: Saudi Invitation to Iran FM ‘Not Enough’; Riyadh Should ‘Change Policy,’ Fars News Agency, 19 May 2014.

[4] “Takfiri Threat to Boomerang on Backers: Leader,” Press TV, 2 June 2014.

[5] “10 Reasons Why Zarif was Invited,” Rouhani News, 29 May 2014.

[6] For a recent example, see “Iran Arrests Takfiri Terrorist Commander in Northern Province,” Iranian Diplomacy, 28 May 2014.

____________________

Alex Vatanka specializes in Middle Eastern affairs with a particular focus on Iran. From 2006 to 2010, he was the Managing Editor of Jane’s Islamic Affairs Analyst, based in Washington. From 2001 to 2006, he was a senior political analyst at Jane’s in London where he mainly covered political developments in the Middle East. He joined the Middle East Institute as a scholar in 2007. Since 2006, he also lectures as a Senior Fellow in Middle East Studies at the US Air Force Special Operations School (USAFSOS) at Hurlburt Field. This article was originally published in the Middle East Institute.