Imagine this: A prestigious German university is offering an online audiovisual course to help both Germans and foreigners learn about “National Socialist Thought” (that is, Nazism). An introductory video, posted to YouTube and linked by major American media sites, shows a smiling professor and students inviting the viewer to explore the contributions of Adolf Hitler to Germany’s historical and philosophical heritage. No mention of the Holocaust or World War II accompanies the course, and reportage on it also glosses over those details.

This is, of course, unthinkable, and, in many nations, illegal. No discussion of Hitler or Nazism escapes the industrialized murder of 12 million people in the Nazi “Final Solution” and the six-year-long war launched to carry it out. Nazism, with its harrowing visions of concentration camp victims and gas chambers, is something Germans and the Western world have overwhelmingly pledged never to forget and never again to allow.

When it comes to the communist ideology of the Chinese regime, however, a rather different narrative seems to be in order.

The New York Times recently published an article about a Tsinghua University course on Mao Zedong Thought. Appended is an 8-question multiple-choice quiz with questions taken from the renowned Beijing institution’s course content addressing the verbose and often vague theoretical underpinnings of Maoist ideology.

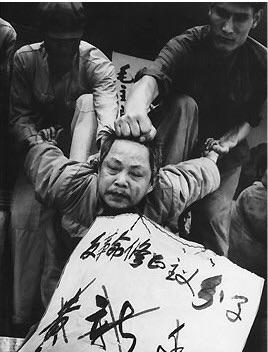

But as it detailed the audience’s unenthusiastic reactions to the course, the Times article, like the Tsinghua course itself, neglected the context of terror and mass killing—all in all, a human toll numerically rivaling the casualties of both world wars combined—that accompanied Mao’s communist theories.

Between cataclysmic political movements such as the Great Leap Forward, the violent land reform campaigns, and the 10-year Cultural Revolution, the Times swallows this up as “famine” and “chaos” in its reportage.

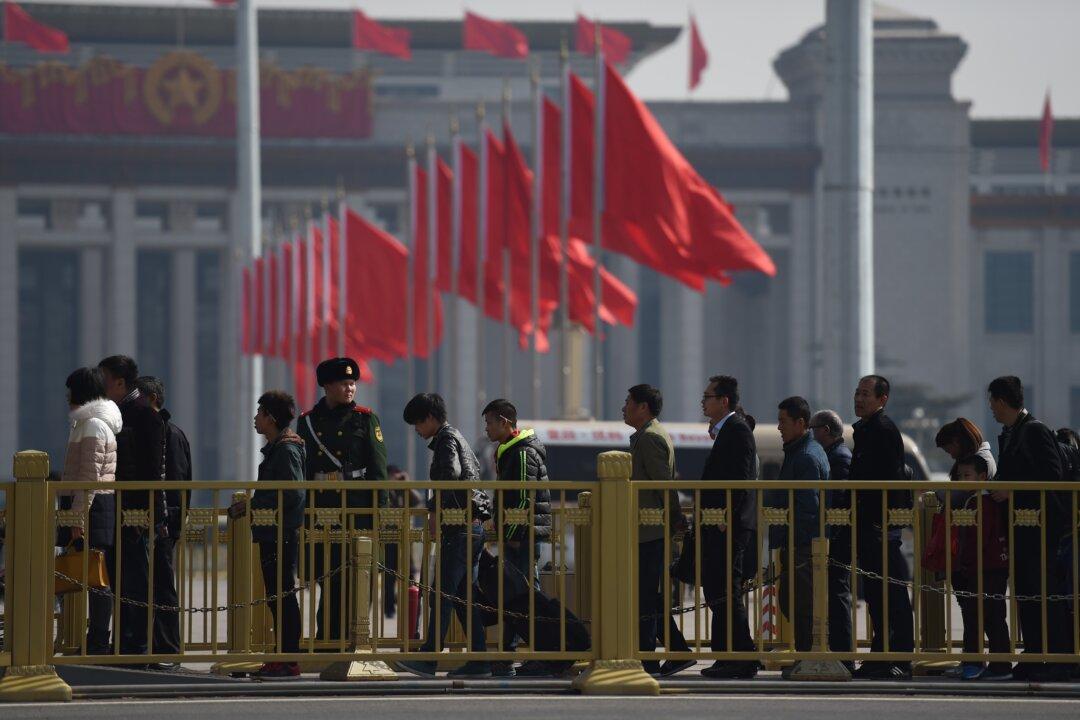

In this sort of historically incomplete narrative, Mao Zedong Thought and Chinese communism in general remain a curiosity, a vestigial holdover from a China that has supposedly grown out of its backward past. Communist slogans and propaganda appear as a face-saving measure, like a crutch for the nation to complete its path to a better future.

Conveniently for the Chinese regime, this isolated, decontextualized understanding of the People’s Republic’s founding dictator, and the ideology the Party continues to enshrine, belies ongoing persecutions against marginalized religious and ethnic groups.

The 16 years of repression against the Falun Gong spiritual discipline, for instance, has seen all range of methods—including the harvesting of organs from tens of thousands of living prisoners—applied in the Party’s efforts to destroy this meditative practice in the name of opposing superstition and upholding the communist demand for atheism and materialism.

The portrayal of the Party’s stated ideology as an economic and political anachronism, detached from both historical and ongoing abuses, ignores the continued relevance of communist thought in shaping the Chinese regime’s motivations and actions, as well as the nature of the plight facing its living and dying victims.

Leo Timm is a reporter for Epoch Times.