A couple of weeks ago, we were treated to a total lunar eclipse – and on Thursday afternoon, North America will see a partial solar eclipse.

Each month, at the time of new moon, the sun and moon are together in the daytime sky. Most of the time the moon passes by unnoticed.

But at least twice a year, somewhere on Earth will see the moon pass in front of the sun and the spectacular phenomenon of a solar eclipse occurs. (You can check when your part of the world will next see one on NASA’s solar eclipse catalogue.)

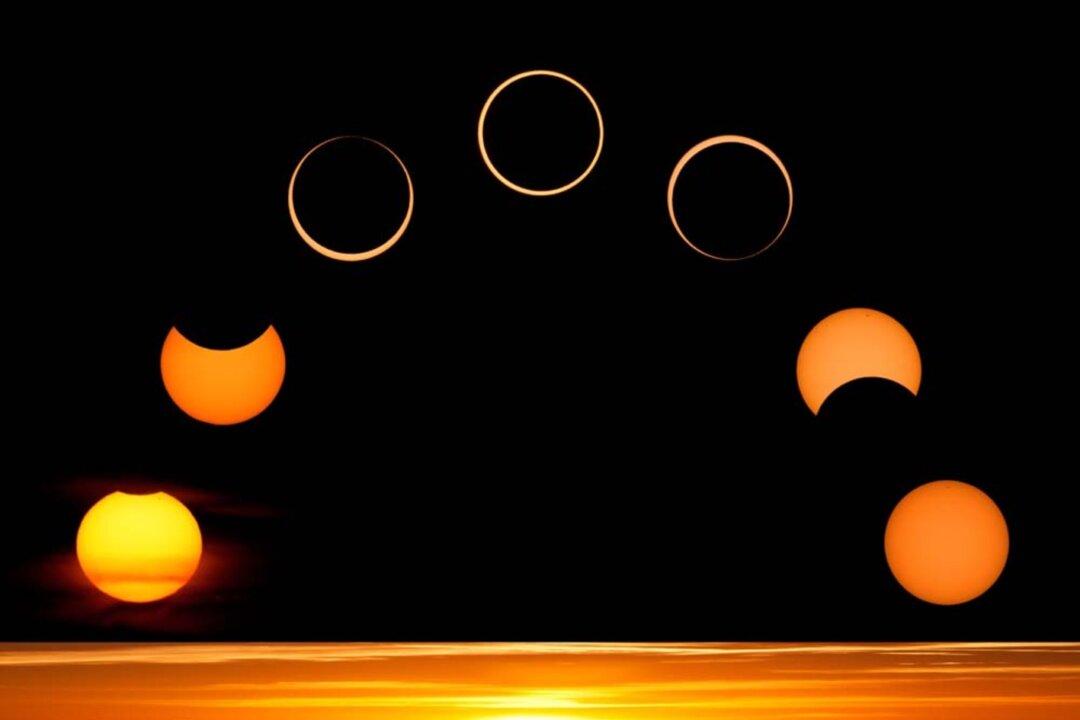

While sometimes the moon perfectly hits its mark and the sun is dramatically hidden from view in a total solar eclipse, it’s also possible for the moon to line up directly with the sun but not block it out completely.

In this circumstance, called an annular eclipse, a ring of sunlight shines out from around the dark moon.

But most commonly we experience a partial solar eclipse. In this instance, the moon’s path only partly crosses the sun and by using the right sort of equipment, it’s possible to see a chunk of the sun disappear behind the moon.

Size Matters

It comes down to coincidence that it’s at all possible for a total solar eclipse to occur. The moon is much smaller than the sun, but it’s also much closer. By diameter the moon is about 400 times smaller and by distance it’s roughly 400 times closer.

This perfect match means that to us on Earth, the sun and moon appear a similar size.

But there’s more. Anyone who’s been aware of the supermoon craze that has developed in recent years, will also know that the moon’s apparent size varies slightly throughout the month. This is because the moon travels along an elliptical orbit around the Earth. (The size of the sun varies too due to the Earth’s elliptical orbit, but it has a much smaller effect.)

The changing size of the moon affects what sort of solar eclipse will be seen whenever the moon passes directly in front of the sun.

If a solar eclipse occurs when the moon is near apogee (or furthest from Earth), then the moon will be appear too small to completely cover the sun. A thin ring of sunlight remains in view, creating an annular eclipse.

Since the moon is further away, it is the moon’s antumbral shadow that touches down on Earth. This section of the moon’s shadow extends beyond the umbra or the shadow’s darkest part.

A total solar eclipse occurs when the moon is close enough for the umbra to reach Earth. And the closer the moon is, the longer totality lasts. On rare occasions totality can extend for just over seven minutes. But most of the time it lasts only a couple of minutes or so.

Right Time, Right Place

Whenever the sun, moon and Earth fall into line to produce a solar eclipse, there’s only a limited part of the Earth that is cast into shadow.

In 2012, NASA astronaut Don Petit captured a solar eclipse from on-board the International Space Station. From this incredible view point, it was possible to see the moon’s small shadow zip across the planet at nearly 2,000 km/h.

Petit’s images captured an annular eclipse and only places near the very centre of the shadow saw the sun become a ring of light. But the same is true for total solar eclipses also. It is only near the centre of the moon’s shadow that totality is seen.

All other regions within shadow see a partial eclipse. These places lie within the moon’s penumbral shadow that is much larger than the umbra or antumbra.

Sometimes, the alignment of the sun, moon and Earth is not perfect and nowhere on Earth sees the moon directly pass in front of the sun. This is a truly partial eclipse and only the moon’s penumbral shadow falls upon the Earth.

Interestingly, on rare occasions an eclipse can be both a total eclipse and an annular eclipse. It all depends upon where on Earth you are watching it.

Known as a hybrid eclipse, what happens is that the Earth lies very close to the sweet spot, between the umbral and antumbral shadows. Amazingly, the curvature of the Earth is enough to bring some places into the umbra to create a total solar eclipse, while others are a touch further away and fall into the antumbra to see an annular eclipse.

During a solar eclipse, the shadow cast by the moon is so small and moving so fast that the eclipse tracks a thin path across the Earth. Each place along the path sees the eclipse in its own time.

This is very different to a lunar eclipse, where the moon is engulfed in the Earth’s much larger shadow. Lunar eclipses are seen from the entire night side of the Earth and everyone, no matter where they are, witnesses the event at precisely the same moment.