A beautiful full moon is set to rise this Sunday night, August 10. It will be spectacular and I encourage everyone to go outside and have a look. But the question is: will it be a supermoon?

Technically yes: by the definition that’s fallen into common usage, it will be a supermoon. By this I mean that the full moon will coincide with the moon being slightly closer to us, as it travels along its elliptical orbit around the Earth.

Will we notice that this moon is bigger and brighter than any other full moons to be seen this year? It might be nice to think so, but in all honesty it’s not really possible to spot the effect.

The moon is impressive as it is; being a little bit more impressive on odd occasions like this doesn’t make it stand out any more. But what it does do is give us the opportunity to think about our neighbour in space.

What’s in a Name?

To set the record straight, the term “supermoon” comes from astrology. It was coined by Richard Nolle a “certified professional astrologer” in an article for Horoscope magazine in 1979.

Unfortunately, Nolle uses it to argue that this kind of moon will trigger cataclysmic events because of the extreme tidal forces at work. It won’t – the variations will bring about a tide that in most places is only a few centimetres higher than usual.

I must admit though, that supermoon has a better ring to it than perigee moon, which is the scientific expression.

Perigee denotes the point in the moon’s orbit when it passes closest to Earth. It brings the moon about 50,000km closer than at apogee when the moon passes furthest from Earth.

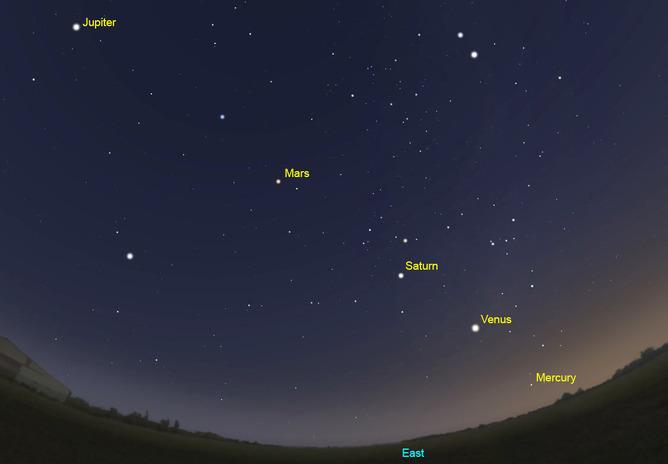

The full moon occurs at various distances from Earth across the year. (Museum Victoria/MICA)

In the graph above, I have plotted the distance of each full moon throughout the year and you can see that this month’s full moon, at a distance of 353,552km, will be the closest for the year.

It just beats out last month’s by about 800km and it is almost 58,000km closer than the January full moon. Sounds impressive, right?

This change in distance, of about 14%, compares the perigee moon of August to the apogee moon of January. Not only are we relying on memory but the moon already looks big in the sky, so it’s quite a small relative change to notice.

Furthermore, most of the full moons we see across the year occur somewhere between these two extremes.

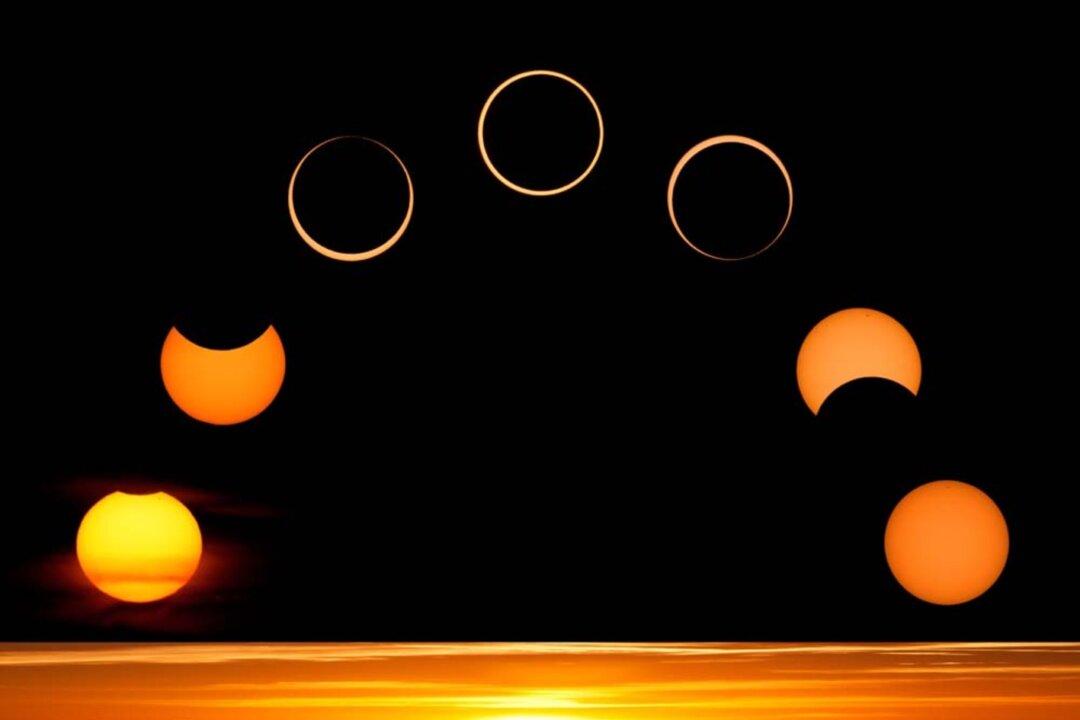

The supermoon of 2011 compared to an ordinary full moon. (Marco Langbroek)

Of course if the moon is closer, then it’s also brighter. Sunday night’s full moon will be about 30% brighter than the one from January. But again, the moon is already the brightest object in the night sky, so spotting a difference looking at the moon is nigh impossible.

Lunar Myths

The supermoon seems to be one of those stories that will just continue to hang around. Like the folklore that hospitals are busier on nights of a full moon or that the moon affects us in weird ways.

There is one moon phenomenon that is not yet explained and that is the moon illusion. It’s the idea that most of us perceive the moon as being bigger when it’s on the horizon compared to when it’s high up above in the sky.

When you are looking at the moon on Sunday night, measure it by putting your thumb in front of it or roll up a piece of paper to match the moon’s diameter as it appears large upon the horizon. Then do the same when the moon is higher in the sky and you'll see that the change in size is all in your mind.

The Ebbinghaus illusion and the Ponzos illusion are often used to explain it, but researchers from the Susquehanna University, Pennsylvania have put forward that it may stem from us perceiving that the moon is closer on the horizon, while at the same time our binocular vision is telling us its not.

If you want to see a truly magical moon, then go no further than the video above. It is real time footage of the moon captured from New Zealand with a super telephoto lens and a great deal of creativity. Can the moon really get more stunning?

![]()

Tanya Hill is an honorary fellow of the University of Melbourne and Senior Curator (Astronomy) at Museum Victoria. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.