It’s a tough job trying to predict what will happen next in the murky political environment swirling around the oil and gas industry. International figures regularly emerge from the sidelines to thwack industry with left-field comments. Wealthy activists fund sophisticated political advocacy campaigns to block market access while oil gets carted to port by rail, leaving prairie grain to lie dormant in massive silos. Quebec’s moratorium on fracking continues. And despite best efforts at building progressive relationships with First Nations, cleavages with government and industry remain.

Gone are the days when the sector would keep its collective head down and wait for storms to pass. Today, rebuttals are swift (if overly focused on how many airplanes were used to fly critics to northern Alberta), and industry is getting better at demonstrating its growing social and environmental performance – their bundle of work usually packaged as “corporate responsibility.”

But, as the debate over development grows more caustic, sorting truth from fiction (and regulatory reports from rumour) can be tough for the average citizen. Heavy lobbying on both sides has netted decently strong public support for at least one project, TransCanada’s Keystone XL pipeline. A February 2014 Washington Post poll shows that Americans approve of the project by a margin of three to one—a largely pragmatic admission, says the Post, that American demand for oil isn’t going down, and better to get it from a friendly supplier that offers jobs and economic growth, two enticements that offset the project’s perceived environmental risk. Despite the fact that politicians tend to follow rather than lead public opinion, it’s anybody’s guess whether legislators are likely to accept this voter analysis and move the project ahead. Still, public support for Keystone in the face of such fierce political opposition should give the sector confidence in the public’s (cautious) appetite for development.

No less challenging than the U.S. political scene is the growing complexity around development on First Nations land, particularly in British Columbia where missteps have undermined relations. Case in point: When the province announced earlier this year that new sweet gas processing plants would not be subject to environmental review–coinciding with a First Nations’ hosted conference on LNG development–the response was swift and dramatic. Government representatives were literally drummed out of the conference for their lack of consultation. The environment minister quickly reversed the decision (one commentator called it “shockingly stupid”), but relational trust was nevertheless undermined.

Still, some observers believe that the charged political landscape in B.C. represents an opportunity, rather than an impenetrable roadblock. Jack Toth is one of them. He’s CEO of Impact Society, a social enterprise focused on forging positive relationships between industry and aboriginal communities. To realize the opportunity, Toth says, industry has to change its mindset about how to work with First Nations. “Businesses need to move from doing things for the communities and start being involved with them. Then they'll see what their real needs are, and help them achieve them.”

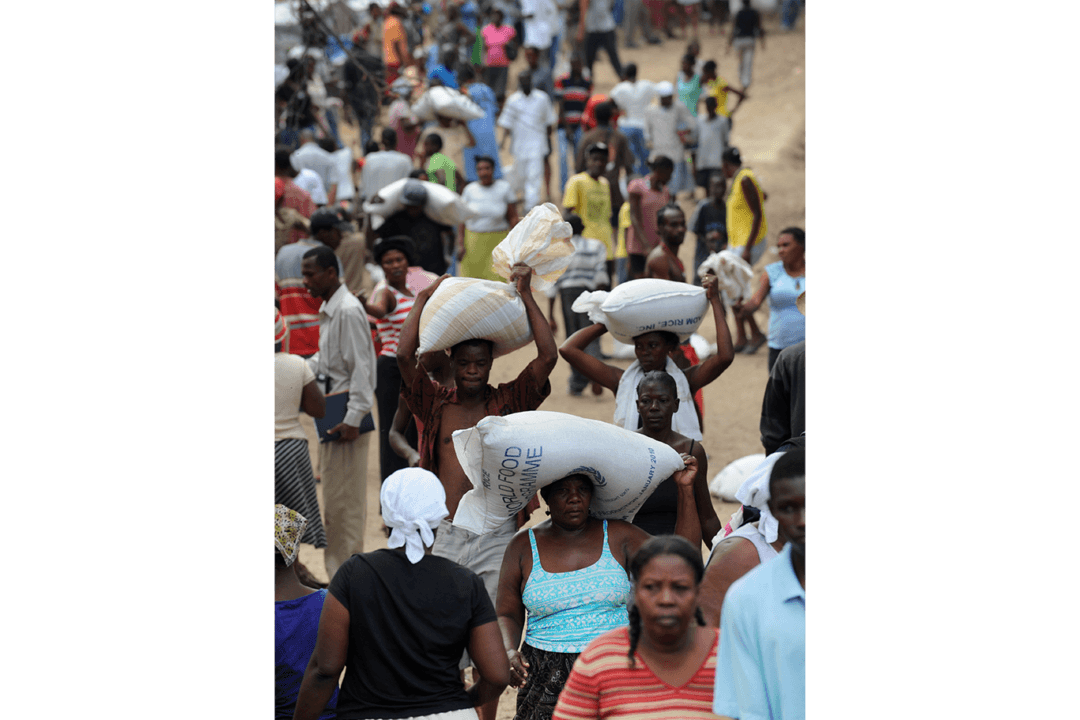

With more than 600 major resource projects worth approximately $650 billion planned for Canada over the next 10 years (those statistics are from The Fraser Institute), First Nations communities know full well that they have a huge opportunity to benefit from development. “These communities want to move beyond an exchange of money for resources toward genuine partnerships.”

In particular, resource companies need to think about funding long-term needs rather than short-term wants. “There is a dependency trap in many aboriginal communities, and investment should focus on infrastructure support that gives individuals and families the keys for self-sufficiency,” says Toth. More than education and skills training, this is as much about effective parenting, youth, and adult self-development–the basis for personal and community growth.

The question for Toth is whether industry is willing to roll up its sleeves and get involved. Despite negative history, Toth says there is tremendous willingness by many First Nations to be generous with industry, especially when it shows a willingness to go deep. One illustration: A few years ago, Toth and an industry CEO were invited to join a First Nations community in an important spiritual ceremony. Both were overcome by the honour of being welcomed into the inner circle of the community, a reflection of the trust and respect each side had earned from the other. “This is where relationships can get to if industry is willing to engage on a meaningful level. It’s not always easy,” he adds, “but it sure beats the alternative.”

Joni Avram is a consultant to donors, businesses, and non-profit enterprises seeking credibility, influence, and support through effective marketing and engagement strategies. You can follow Joni on Twitter @joniavram.