Fresh on the heels of Black Friday, which is to consumerism what Thanksgiving is to gluttony, comes “the giving season,” a chance, perhaps, for the public to assuage their guilt over overindulgence by contributing to a charity or two as part of their holiday giving. Nonprofits receive a big chunk of their annual revenues in December, thanks to a spike in giving by last-minute donors.

It’s easy to get wrapped up in holiday sentimentality or in the passionate pleas of a celebrity who engages us to give to another “worthy” cause. But before we give, we should think. Robert Lupton, author of “Toxic Charity,” writes that although the “compassion industry” is almost universally accepted as virtuous, its outcomes are almost entirely unexamined. So let’s examine.

Could it be that, despite our best intentions, heartfelt concern, and billions of dollars, much of our charitable giving has little real impact—and even does more harm than good? That in many cases, charity is still doing for people what it should be enabling them to do for themselves, and perpetuating one-way giving that diminishes their dignity and increases dependency?

At a recent conference, Dan Lavin, an international development worker, recounted stories of well-intentioned aid agencies unintentionally displacing local businesses and undermining the sustainability of emerging communities. An African wheelchair company that designed and manufactured beautifully crafted devices perfect for their geography, was struggling to grow because of the glut of foreign-donated wheelchairs—devices that didn’t even function well in the African countryside.

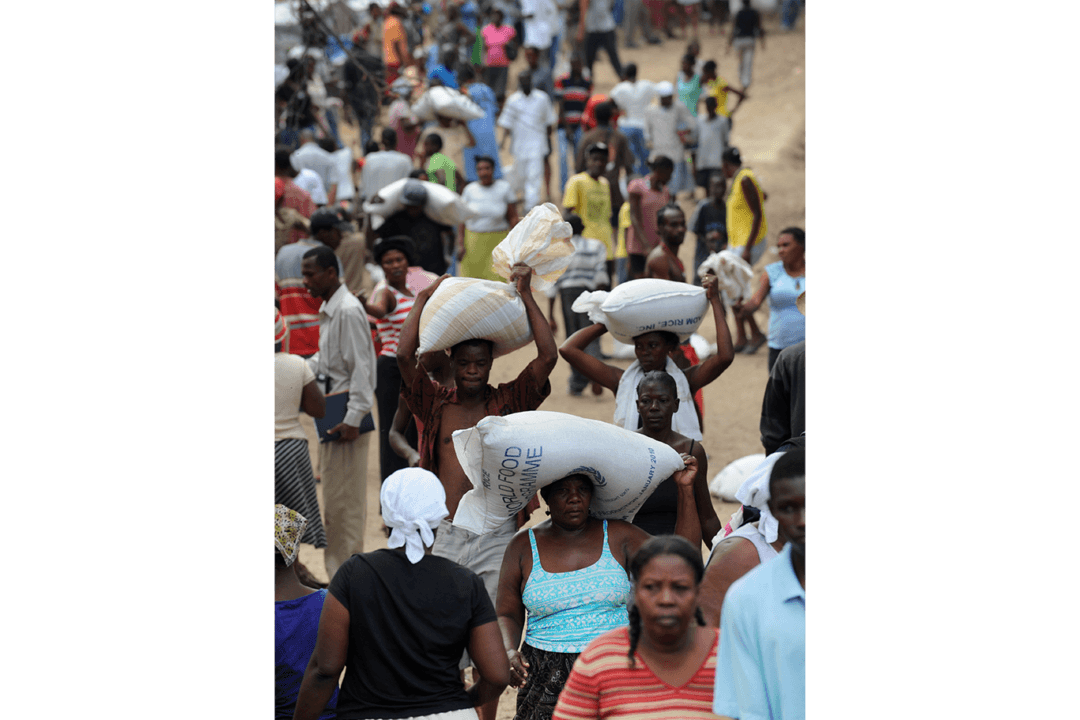

He told of Haitian farmers being unable to compete with the tons of donated foreign rice that poured into the country following the 2010 earthquake. He talked about the 25 years he spent convincing a small community in Ghana to build its own school—and having them finally agree—until a church from the United States called to tell them they'd be building one for them.

As Lavin talked, the implications of poorly conceived international aid became clear. By throwing money at problems, and directing outcomes, rather than engaging locals in finding their own solutions, charity can be damaging. The underlying issues never get tackled, and local communities are impeded from becoming self-sufficient.

Timely case in point: It’s been 30 years since Band Aid launched a fundraising tsunami to attack the famine in Ethiopia—eventually raising hundreds of millions. Now that Bob Geldof is promising to resurrect Band Aid once again, at least some aid experts criticize Band Aid as fundraising success and a development failure—one that has neglected to address the underlying issues, ultimately doing more harm than good.

What’s the solution? Lupton offers an example of effective charity: His church converted its food pantry into a food co-op that is owned by, run by, and funded by the members who use it—the members buy the food and distribute it, and collaboratively make decisions about how the coop will run. In the process, they are not disabled by handouts, but empowered and equipped to regain their dignity and grow in self-sufficiency.

At the same conference Dan Lavin attended, Howard Weinstein talked about Solar Ear, a social enterprise that designs and manufactures hearing aids with solar-powered rechargeable batteries. Solar Ear hires deaf workers to design and develop its products, providing much needed employment and affordable hearing solutions for the hundreds of millions in developing countries with hearing loss. These devices make it possible for people with hearing loss, living in poor countries, to get an education and break the cycle of poverty.

This trend toward asset-based development is based on a belief that the poor and needy have strengths, and have the potential to be actively involved in solving their problems—with support.

Warren Buffett is famous for saying that giving away money is easy, but doing it well is “fiendishly difficult.” Perhaps that why many approaches to charity are usually not well thought out. The issues are huge and the solutions complex. We live in a world of instant gratification. Random giving remains common. Random asking is even more common. With notable exceptions, in comparison to our efforts in business or government, there may be no other important endeavor for which we hold ourselves to so little account.

Despite calls for more thoughtful giving, for many, the spirit of generosity is still enough. But unless we change the way we think about and do charity, the world may be better off if we all just went shopping.

Joni Avram helps donors, businesses, and nonprofit enterprises gain credibility, build influence, and grow support through effective marketing and engagement strategies. Her expertise has helped generate millions for philanthropic initiatives, focused on effective collaboration, blended value, and social outcomes. She will be writing regularly on philanthropic issues. You can follow Joni on Twitter @joniavram Copyright TroyMedia.com.

Opinion

Are Your Charity Dollars Doing More Harm Than Good?

Haitians carry bags of rice given as food aid on Feb. 11, 2010, at a camp for people that have been displaced from their homes by the deadly earthquake that struck Haiti on Jan. 12, 2010. Roberto Schmidt/AFP/Getty Images

|Updated: