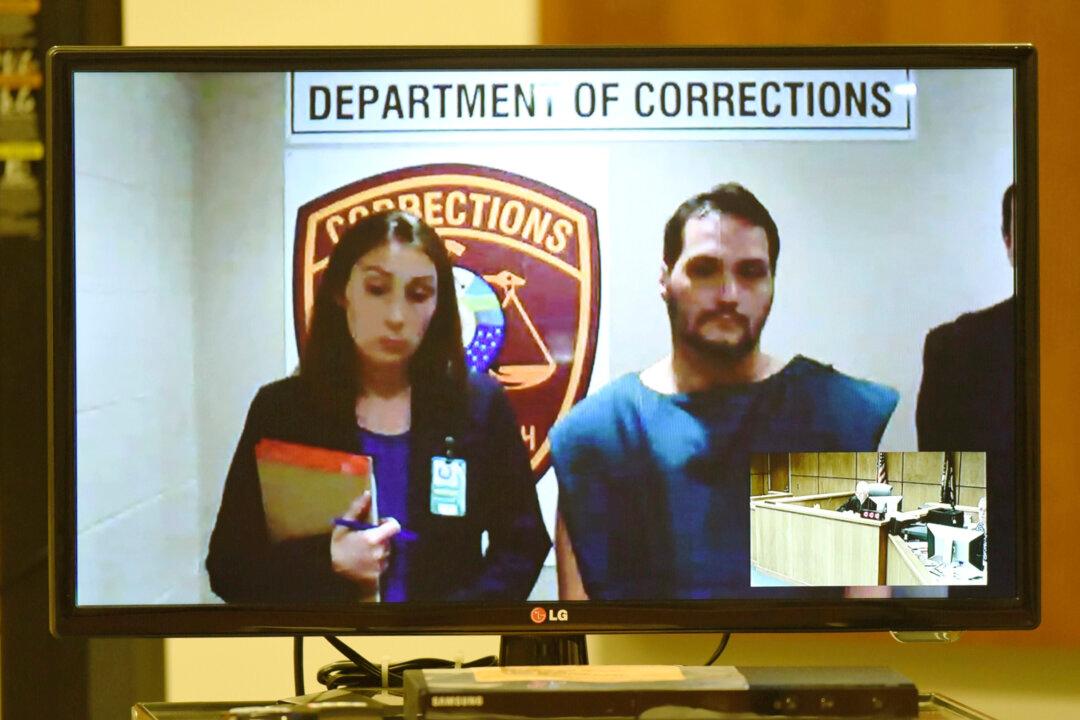

CONCORD, N.H.—It’s now a rare sight to have an incarcerated suspect appear in person for an initial appearance in New Hampshire, where all but one district courtroom are wired for video arraignments. Instead, they appear on screen from a local jail—a change that officials say enhances security and cut transportation costs.

Video arraignments have been going on around the country for years but are rapidly becoming more prevalent in northern New England, and some defense lawyers aren’t pleased, saying it “dehumanizes” their clients.

Judicial officials said a capital appropriation of $541,000 in fiscal year 2012-13 vastly expanded video capabilities in New Hampshire, which began installing video equipment in several courts in 1997. Vermont is currently working on a pilot program it hopes to expand early next year.

“Certainly there’s a cost in equipment, but we do see in the long run it’s a good investment to make,” said Jeff Loewer, chief information officer for the Vermont judiciary and one of the officials designing and executing the new pilot program. The Vermont legislature allocated $210,000 for the program; another pilot was abandoned in 2011 due to cost and technology concerns.

Loewer said the new pilot program in Burlington has arraigned about 70 defendants via video from the Chittenden Regional Correctional Facility since August. The pilot expands in January to defendants housed at the Northwest Correctional Facility in Swanton. He said

The goals include improving efficiency and courthouse safety but Loewer said court officials see other potential uses for video technology, including remote appearances by witnesses and interpreters.

Maine’s first video arraignments took place in Kennebec County in 2006. Five years later, video arraignments were taking place in all 16 counties, including in five courthouses in sprawling Aroostook County, according to a judicial report.

Maine Judicial Branch spokeswoman Mary Ann Lynch said all Maine courthouses are equipped to do video arraignments but not all do. In some cases, she said, the local jails are too antiquated and don’t have the space to set aside a room for video arraignments.

“In some places, the courthouse is right next door to the jail,” Lynch said. “In those courthouses, a lot of times the prosecutor, defense lawyer and judge feel it’s very efficient to bring everyone over from the jail.”

In New Hampshire, more than 1,100 video arraignments were conducted in September alone. Colebrook District Court is the only of the state’s 32 district courts that doesn’t have video capabilities; its video arraignments take place in nearby Coos County Superior Court in Lancaster.

But some defense lawyers—including one in a recent high-profile murder case—object, saying depicting their clients in a jail setting and jumpsuit taints their being presumed innocent until proven guilty.