The “last mile” of a race, goal, or project is the toughest to complete. It requires focus and willpower, special qualities that burn risk on one end to ignite a massive opportunity on the other.

Turning waste into ready fuel could help push natural gas extraction operations through the last mile in a greener, more cost-effective way.

The burn-off of well gas deemed unusable produces “flares.” Burned up in these flares is an estimated waste of some 300,000 cubic feet of natural gas daily in North Dakota alone—a waste worth tens of millions of dollars monthly. But some industry leaders are turning the waste into opportunity.

North Dakota’s Governor Jack Dalrymple didn’t dodge questions about the problem at the Bloomberg LINK Energy Summit in Washington, D.C., in March. He confessed the flares “are a huge waste.” It is estimated that 30 percent of the gas output is wasted.

But the gas that is being burned off may become useful. North Dakota has “natural gas that contains ethane, butane, propane, and other valuable liquids,” the folksy governor said. When the liquids are stripped out, there is an “incredible opportunity to capture what’s valuable today in flares.”

That’s where GE and Statoil come in. Their idea is to capture the flared gas at the wells, strip out high-value liquids, and sell them on the market. Then they plan to convert the remaining methane into compressed natural gas (CNG) onsite to use as fuel to power drilling rigs in remote areas—the so-called “last mile” of the operation.

Turning Flares Into Compressed Natural Gas

GE’s Jeffrey Immelt hit on many key points in the Energy 2020 keynote. He talked about capturing flare waste and turning it into cleaner burning CNG. This CNG could replace the more expensive diesel fuel that’s used in millions of trucks in the United States, Immelt said. Fuel efficiency would also rise in the shift from diesel to natural gas.

By 2025, “world gas demand will increase 36 percent more than is produced today,” and “42 billion gallons of diesel are used to fuel 2.3 million heavy trucks and 24,000 locomotives in the U.S.” on an annual basis, according to a GE infographic The Age of Gas.

In a follow-up interview, John Westerheide, General Manager of Unconventional Resources for GE, elaborated on CNG and North Dakota’s Bakken basin flare problem. He said the production of CNG has been somewhat complicated thus far, and GE has been making efforts to streamline and simplify it.

“In 2012, GE held a collaborative session with Chesapeake Energy. We asked them ‘What are your problems?’ And they said, ‘Figuring out what to do with gas once it’s out of the ground.’ That kicked off a new avenue of research for GE,” Westerheide said. “Between CNG and LNG [liquid natural gas] for transportation, compression equipment, compressors—we began to look at all of the components. It was a nascent industry. Each time a CNG station had to be built, it was built to spec. Our idea was to make it standardized and modular to increase speed and ease of natural gas adoption.”

What GE is focused on is the big picture: “Building demand and infrastructure, with a network that works, that’s the goal,” Westerheide said in his conversant, fast-paced style.

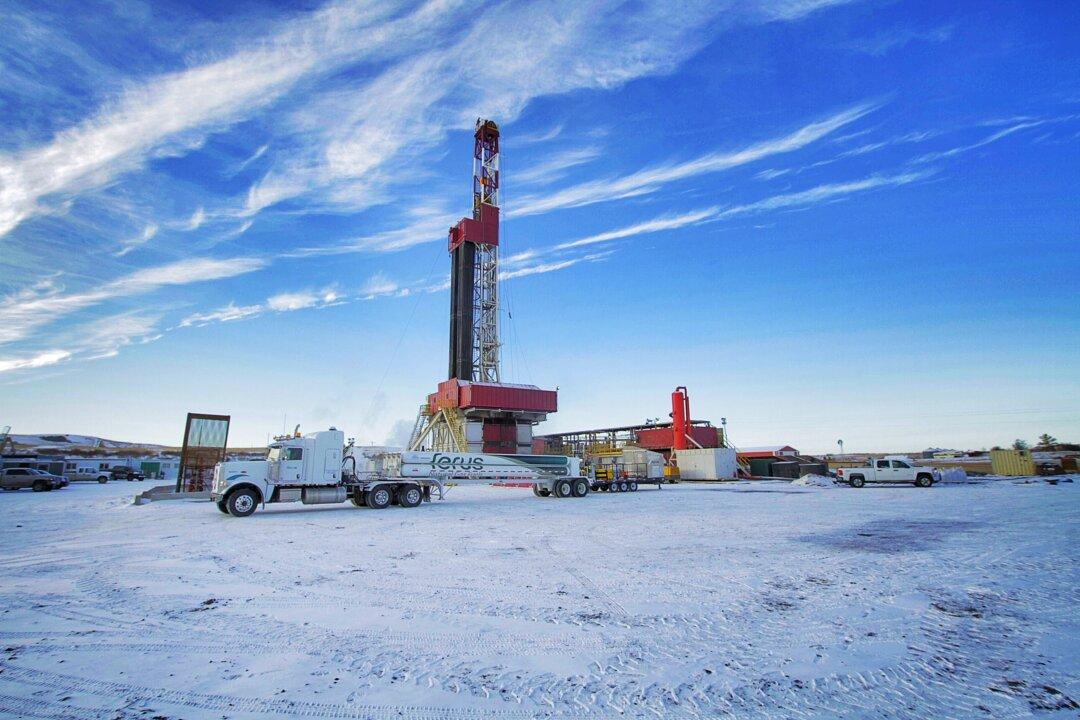

The CNG (compressed natural gas) In A Box pilot project in North Dakota. (Courtesy of GE)

Making CNG Accessible to a Moving Fleet

“We also looked at the flare problem, and then to the rig fleet owners in the Bakken basin,” he said. “Having sold CNG In A Box units [systems for converting vehicle fuel systems to CNG] in the U.S., China, and Canada, we saw how building repeatable CNG stations was helping to grow adoption of the fuel. That same idea could be transferred around the oil fields for rig fueling, to solve the ‘last mile’ challenge.”

Westerheide explained how dynamic the Bakken basin. “150 rigs within eight months can move from one basin to the next around the United States,” he said. “We needed a mobile unit to compete against diesel, which you can get anywhere.”

The other challenge for the pilot project was, explained Westerheide: “Drill rig crews are mobile. They’re continuously moving around. We saw we were missing a logistics partner. We found one in Ferus Natural Gas Fuels,” he noted. “In the Bakken we are moving molecules. With Ferus having worked in Canada’s Oil Sands, which is remote with harsh conditions like Ice Road Truckers, we needed a partner with moving competency and experience. We have the technology, now we need to create the system, form a partnership with the whole network for quick deployment.”

Lance Langford, vice president of Statoil North America Production & Development at Bakken, explained in a phone interview: “Originally, gas systems lay line from one well to another. How do we transport that around the field? If we used a full stream of gas, emissions would increase. … Large plants are more expensive to build, are static, not mobile.”

“GE’s CNG In A Box units, the original design was for mobile gas stations, was attractive to us. Take existing technology on one skid, design types of gas tailored to each field, since every field is different. We are now conducting the three-month pilot study and will expand on it further,” he said.

From there, Statoil will see how it works and how much it costs. Like GE, Statoil will run its own full-scale cost model.

Echoing what GE’s Jeffrey Immelt said at the Energy Summit, Langford put the near future in perspective: “Globally, there is going to be high demand for energy. Infrastructure has to be built to match that growth. While we do that, the industry wants lower emissions. So The Last Mile project is a win at many levels.”

Clean up the flares, convert the wasted gas into CNG, and deploy it to fleets of trucks in the transportation industry.

Langford said, “We must dream big on how we will get the infrastructure done.”