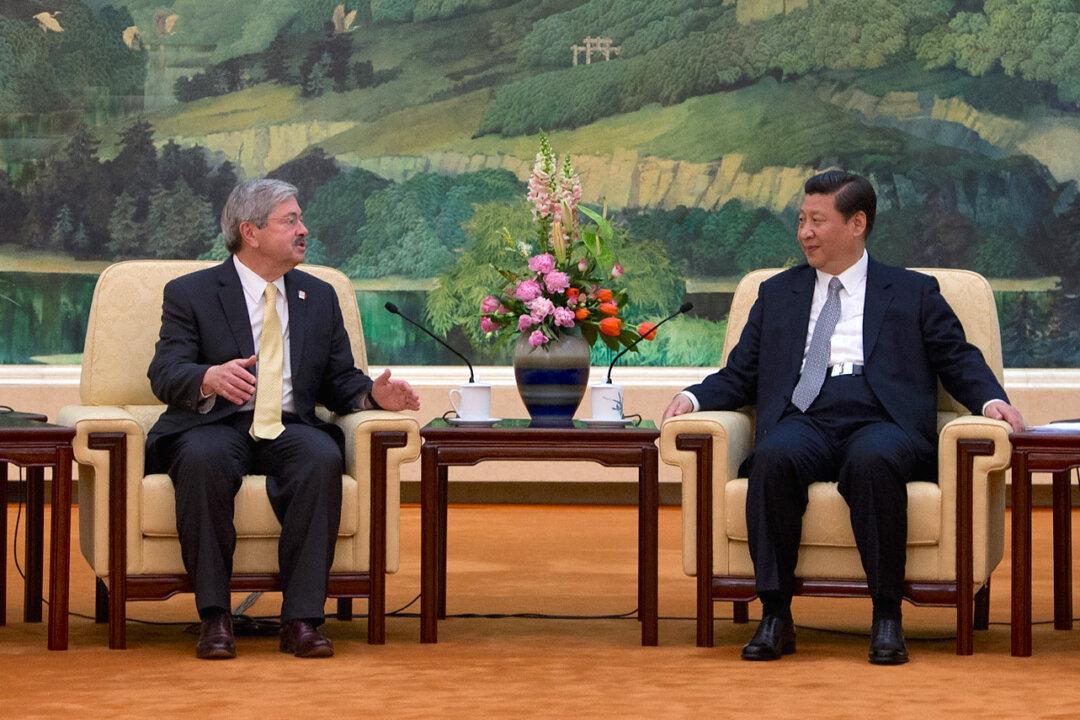

NEW YORK—When Terry Branstad first met Xi Jinping in 1985, Branstad was governor of Iowa and Xi was an agricultural official in northern China. For two weeks, Xi stayed with a family in the town of Muscatine, an experience he fondly recalled when visiting Iowa and Gov. Branstad in 2012 as vice chairman of the Chinese regime.

Xi, now leader of China, will soon get to host Branstad in Beijing.

President-elect Donald Trump picked Branstad, 70, for the post of U.S. ambassador to China. The appointment of Branstad, a six-term governor who has maintained a cordial 30-year relationship with Xi, could prove pivotal for both the Trump and Xi administrations in the coming months.

Branstad and his wife Chris met Trump and his top advisers at Trump Tower in New York on the afternoon of Dec. 6.

“I’m really excited about the quality of people that he’s attracting to the Cabinet,” Branstad told reporters after an hour in Trump’s office. “I’m very proud to have supported Donald Trump for president.”

Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Lu Kang welcomed Branstad playing “a bigger role in advancing China–U.S. relations” when asked about the Iowa governor’s likely appointment in a regular press briefing on Dec. 7.

Branstad is an “old friend of the Chinese people,” Lu said. The feeling might be mutual: Branstad has led four trade missions to China in the past six years and maintains good relations with Xi, whom he called a “long-time friend” when Xi visited Iowa in February 2012.

Branstad is also a friend of Trump. He worked very actively on Trump’s behalf in the general election, and his son, Eric Branstad, managed Trump’s campaign in the state. Trump carried the state with 51 percent of the vote, versus 42 percent for Hillary Clinton.