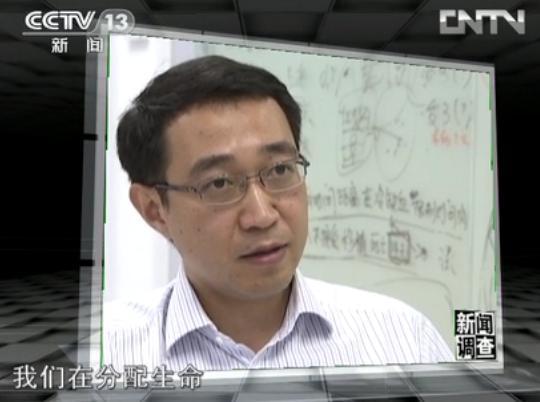

Wang Haibo, an unofficial spokesperson on China’s organ transplant policies, recently told a well-known German journalist that the Chinese regime had no intention of announcing a schedule for weaning itself off the use of organs from executed prisoners.

“The question is, ‘When can China solve the problem of the shortage of donor organs?’ I wish we could end it tomorrow. But it requires a process,” he said in a radio program on ARD, a major German public broadcast network.

“Many things are beyond our control,” he added. “Therefore, we can not announce any time schedule.”

The journalist, Ruth Kirchner, said that Wang agreed to the interview “after long hesitation, because organ donation connected to the death penalty is a sensitive issue in China.”

Wang, director of the China Organ Transplant Response System Research Center at the Ministry of Health, would not say how many organs come from executed prisoners. Some outside groups suggest that there are 4,000 executions per year, though only a portion of those would yield organs viable for transplant.

One of the major disputes that international Western medical groups have with the Chinese authorities is its practice of harvesting the organs from executed prisoners.

In the way this is generally meant by the Chinese authorities, the term refers to organs from criminals who are sentenced to death and have their organs extracted after they are executed given that, at least in theory, they and their families have signed a consent waiver. Families are also entitled to compensation for agreeing to the organ extraction.

Both The Transplantation Society and the World Health Organization forbid the use of organs from executed prisoners, because they say that there can be no true consent from a prisoner on death row.

Many analysts also point to a more sinister source of prisoner organs: those that come from executed prisoners of conscience, who are not formally sentenced to death through the courts for any crime, but who are held in arbitrary detention, blood-tested, and killed for their organs as required.

Reports emerged in 2006 and 2007 of the widespread harvesting of practitioners of Falun Gong, a spiritual discipline heavily persecuted by the Chinese regime. The extent to which the practice persists to this day is unknown, due to the lack of transparency in Chinese data and the secrecy of the persecution.

Wang’s remarks are the second set of high-profile comments from a top Chinese transplant official that openly sets forth what appears to be a new official public stance on the use of prisoner organs.

In March, Former Chinese Vice Minister for Health Huang Jiefu said that hospitals and judicial authorities should form ties in order to source organs.

These new remarks have been a break from what was the previously accepted, and stated, official view. For the last six years, and in particular the last two, the Chinese had promised to move to a system of purely voluntary donation, and vowed repeatedly that it would phase out the use of prisoner organs.

In an interview with the World Health Organization in late 2012, Wang himself affirmed this shift in policy by China. “While we cannot deny the executed prisoner’s right to donate organs, an organ transplantation system relying on death-row prisoners’ organs is not ethical or sustainable,” he said. “Now there is consensus among China’s transplant community that the new system will relinquish the reliance on organs from executed convicts.”

That has evidently changed, to the consternation of international transplant officials who for years practiced quiet diplomacy with China in an effort to bring it around.

A letter by two major international medical organizations, including The Transplantation Society, said that the Chinese practice of taking organs from executed prisoners was “scorned by the international community.”