The Chinese Communist Party’s army of censors recently appear to be allowing political discussions on Chinese social media involving a retired but still powerful Party chief, previously a highly taboo topic.

In speculating on Party leader Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign will take in 2016, many Chinese Internet users on popular Chinese microblogging website Sina Weibo feel that Xi should gun for the political backer of the so-called “tigers and flies”—high-ranking officials and lowly journeyman cadres—if he wants lasting success.

“Although many tigers have been purged, the tiger king remains. Some provincial level officials still have faith in the tiger king,” wrote Hualijia01, a Weibo-verified retired officer from the prosecuting agency in Inner Mongolia, in response to a post on the topic on Jan. 24.

Another netizen claiming to be a graduate of Fujian Normal University wrote: “Publicize the toad’s crimes: a Chinese traitor; sellout to Russia; organ trading crimes against humanity; and gross corruption. This criminal ringleader is notorious worldwide.”

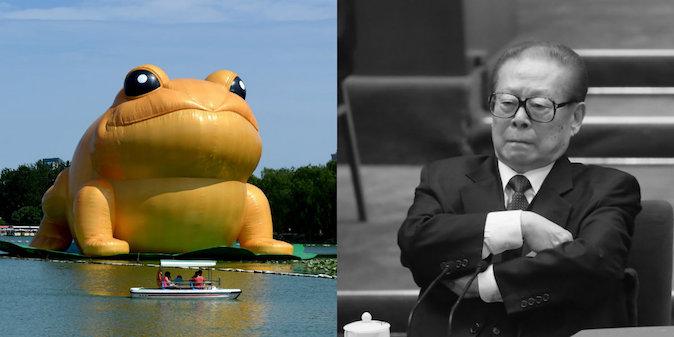

In using the terms “tiger king” and “toad,” Chinese netizens are referring to Jiang Zemin, the former Communist Party boss and paramount regime power for nearly two decades. The non-censoring of netizen remarks and various public political gestures in recent months suggests that Xi Jinping will move to arrest Jiang this year, according to outspoken former Party officials.

Until this January, the regime’s censors have regularly deleted social media posts that use the word “toad” in political suspect situations. (Weiboscope, an online tool that tracks deleted posts on Weibo, lists over 140 keyword deletions in 2015.) Chinese citizens have for some years now referred to Jiang Zemin as a “toad” because bears a close resemblance to the amphibian with his thick, rounded spectacles and droopy, dewlap-like jowls.

The lack of censorship is a sign that Xi Jinping now has an “overwhelming advantage” over Jiang Zemin, according to Xin Ziling, the former director of the editorial desk at China National Defense University, the premier institution of higher education for defense officers in China.