We have a secrecy problem. This may seem odd to say during an era in which the most intimate details of individuals’ lives are on display. Yet government is moving behind closed doors, and this is definitely the wrong direction.

In fact, I’m dismayed by how often public officials fight not to do the public’s business in public. And I’m not just talking about the federal government.

City and town councils regularly go into executive session to discuss “personnel issues” that might or might not truly need to be carried on outside public view. And let’s not even talk about what can go on behind closed doors when it comes to contracting.

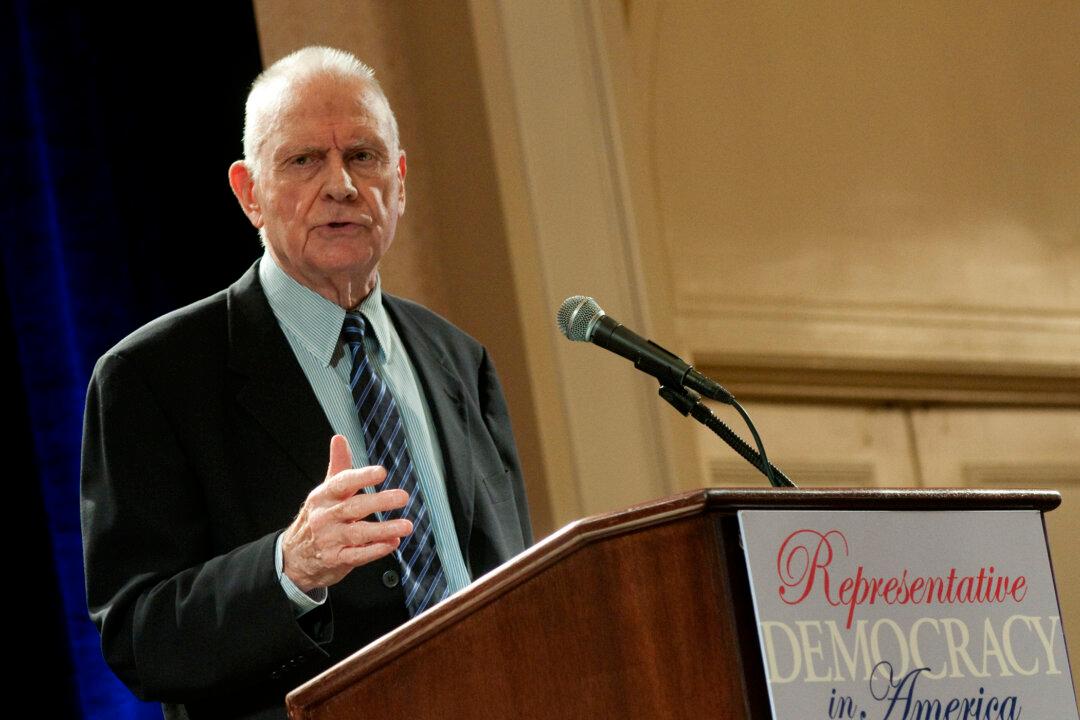

Representative democracy depends on our ability to know what's being done in our name.