We’re in the middle of the presidential debates, and, not surprisingly, they’re drawing viewers in great numbers. The contest is close, and the chance to watch the two candidates spar with one another face-to-face makes for entertaining television.

This is hardly a bad thing. Overall, presidential debates are a plus for the public dialogue. They get tremendous coverage throughout the media universe, both while they’re taking place and in the days that follow. They let the voters see the candidates under pressure and gauge their performance. As scripted as they can sometimes seem, they still let us watch the candidates think on their feet. They’re serious events, and are certainly more substantive than campaign speeches and television commercials.

It’s true that they don’t usually change the trajectory of a race—although we won’t know until election night whether this year’s debates played a role in the outcome. They can reinforce enthusiasm, but it’s rare that they create it from scratch.

Yet I think our focus on debates—at least in the form they currently take—is misplaced. It’s not so much that they reward one-upmanship, a quick wit, and clever zingers—although they do. Rather, I think they don’t actually help us make a good choice.

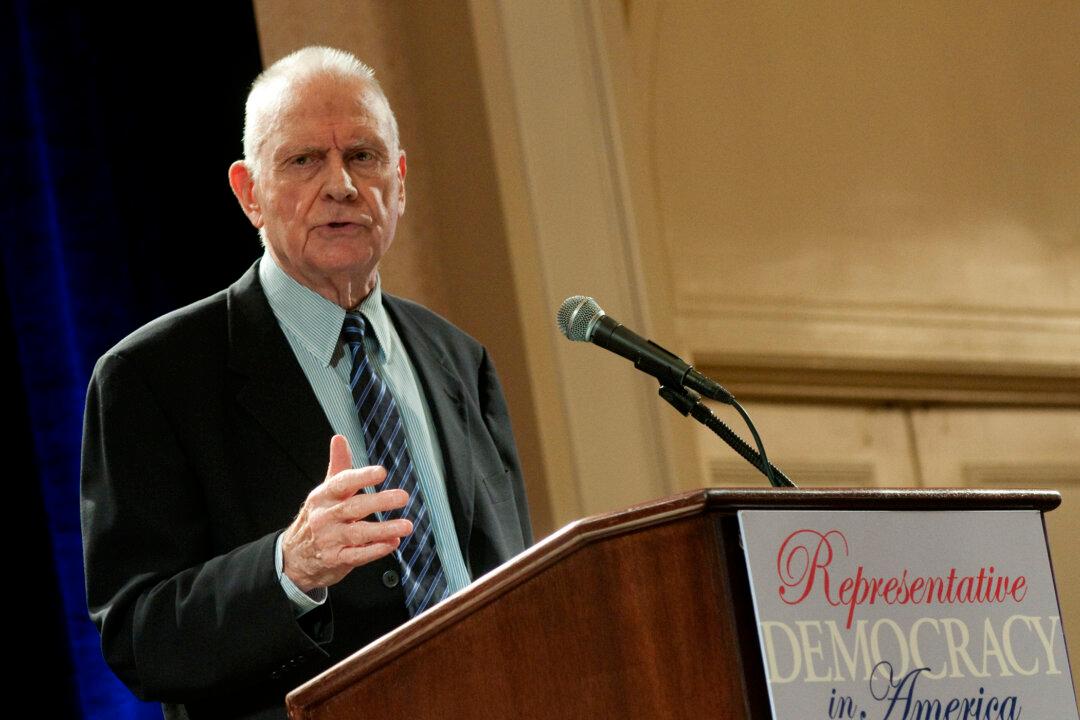

Over my years in Congress and afterward, I’ve sat in on a lot of meetings at the White House where foreign and domestic policy were discussed. For the most part, I came away impressed by the process by which presidents make tough decisions. They go around the room, asking each guest, “What do I do now?” They ask participants to define the issue, lay out the options, identify American interests at stake, and make recommendations. It’s usually a sustained, unhurried process, with very little fancy oratory: instead, I’ve heard sharp debate and thorough discussion characterized by forceful, reasoned, fact-based, and responsible arguments. Presidents pay close attention and sometimes take notes. They want to hear different opinions, seek advice, and then go off and make a decision.

You have to remember that the choices a president has to make are complicated and often very difficult—almost by definition, an issue doesn’t get to that level unless it’s a tough one. I’ve sat in on meetings with both Democratic and Republican presidents, and one of the things that often impressed me is that ideology has played a smaller role than you'd imagine. The conversations are quite pragmatic.