By now many of us heard the Chinese Communist Party’s promises to close its system of forced labor camps. While I sincerely hope this comes to pass, the other forms of detention in China have not gone away—in particular, the regime’s notorious prison system remains as brutal and lawless as ever. I was an inmate of Chinese jails for seven years, and have seen and experienced what conditions there are like.

Abuses in countries outside China have been reported because inspectors are allowed there. But never since the Communist Party came to power in 1949 has it allowed unfettered, independent investigation of its vast detention system. When UN personnel visited in 2005, their movements were severely restricted.

I was detained in the Beijing Qichu Detention Center in 2005, where UN Special Rapporteur Manfred Nowak was allowed to visit. But in the end the UN didn’t manage to get any interviews with Western or Chinese prisoners; they were only allowed to observe the conditions on the cells via monitors. Nowak reported that all efforts to interview former detainees, family members, lawyers, and human rights activists suffered government interference.

The conditions in Chinese prisons are horrible. I saw them. Cells were between 7 and 21 square meters, and between six and sixteen inmates were crammed inside. We slept, ate, and defecated in these tiny rooms. The food was appalling, and not one day passed when we were not physically and psychologically tortured by the guards or “hired” inmates.

Beatings, starvation, and forced labor are all parts of life for those stuck in Chinese prisons. Even minor complaints can result in punishment or even death for yourself or an inmate. Some prisoners I knew tried to commit suicide because the conditions were so abusive. Only some succeeded. Those who didn’t were punished severely.

Guards would sometimes extract confessions from prisoners for the crimes they were accused of: they would break fingers, apply electric shocks, or if they did not want the injuries to show, would simply expose prisoners to the freezing weather, or force them into stress positions for hours.

Embassies in Western countries heard about all this from me, but they did nothing to speak out about it—perhaps because they don’t want to jeopardize their country’s relations with China.

The time I was imprisoned, from 2003 to 2010, also saw China issue new laws and make a lot of promises about improving its human rights policies. Many in the West thought that helping to improve China’s economy, and giving China the Olympics in 2008, would somehow result in more respect for human rights, or even democracy. It was a fantasy. But this fiction, along with corporate greed, has simply helped the Chinese regime cover up the truth of its abuses, while everyone goes about business as usual.

The kowtowing of the West has, of course, also been used by the Communist Party’s propaganda machine to legitimize its rule. The domestic propaganda system, which creates fake films showing how mild prison life is in China, means that the Chinese public is kept in the dark. Foreign media have only shed some light on the conditions in these detention facilities, partly because in-depth investigation may result in their being thrown out of China.

That’s precisely what happened to Al Jazeera after it produced a documentary about the system of slave labor camps, which heavily featured interviews with former Falun Gong detainees.

Excuses about the lack of evidence of abuses also mean that Western countries have put minimal political and diplomatic pressure on the Chinese regime. The regime thus continues to carry out these abuses in the dark, with organ harvesting from living prisoners—some death row prisoners, but mostly Falun Gong prisoners of conscience—being the most appalling.

When I was in the Beijing prison, organ theft was a known and sad fact for all inmates on death row. I spoke to a policeman who admitted to this. “So what?” he said. “They’re going to die anyway, so let the hospitals do what they want with the organs.” I will never forget the time that an inmate recounted to me how he had just met a person from his hometown that was supposed to have already been executed and cremated. This person knew that because the family had received the ashes—two years before.

This made it clear to us all that many inmates were being kept alive simply so their organs could be matched with donors. Then the real execution—or, rather, tranquilization and organ extraction, which leads to death—would take place. A similar process has been used against prisoners of conscience, including some Uyghurs in the 1990s, and a large number of Falun Gong practitioners during the 2000s and up till today. Western countries have not shown an interest in looking closely at these modern horrors, happening right under their noses.

I hope that officials and politicians from democratic Western countries, including the United States, and Sweden where I am from, who interact with Chinese officials, will dare to tell them that they know full well what is happening inside China. I also hope that they will begin demanding that all prisoners of conscience be set free from these facilities.

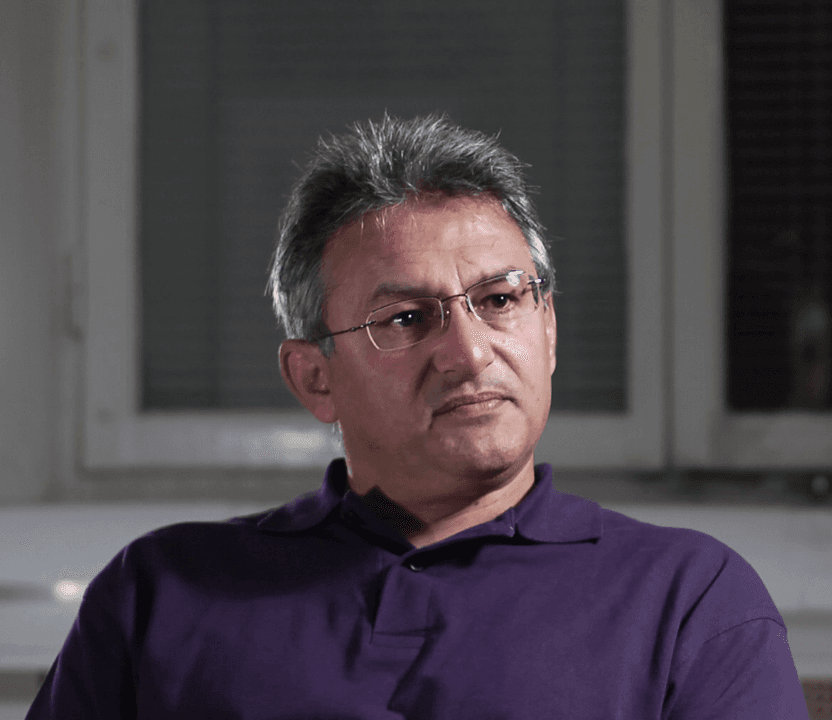

George Karimi is a Swedish businessman of Armenian origin. He was sentenced to life in prison in China after one of his business associates was tortured and accused him of counterfeiting money. He spent seven years in Chinese jails until being transferred to Sweden in 2010; now, after a reduction of his sentence, he is due to be released in November 2015. Mr. Karimi recently completed a book about his experiences.