Religion is anathema to the atheist Communist Party that rules China, and the menu of policy choices for regime leaders has been limited to “crush, control, or co-opt.” The administration of Chinese leader Xi Jinping has, so far, largely remained in this mold.

But even in the face of this panoply of restrictions and punishments, religious believers in China continue to grow in number, according to findings by Freedom House, a human rights NGO based in the United States.

“Despite tightening controls, millions of religious believers defy official restrictions in daily life,” said report author Sarah Cook, a senior research analyst at Freedom House.

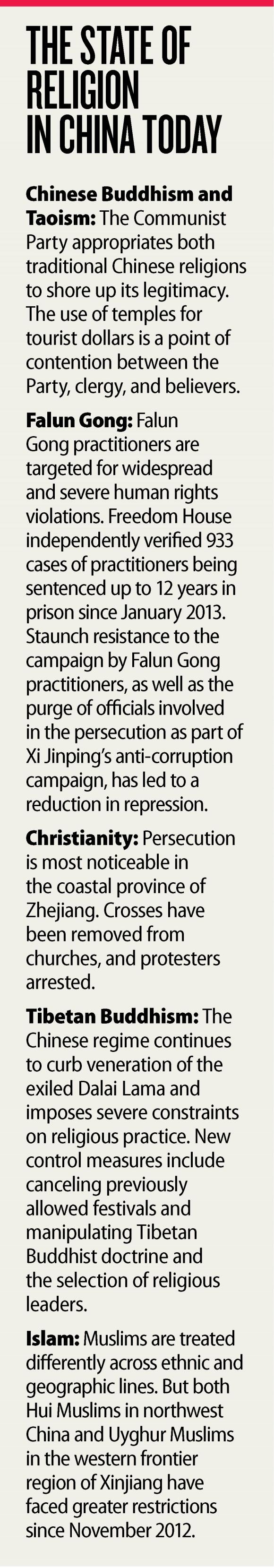

The report, titled “The Battle for China’s Spirit: Religious Revival, Repression, and Resistance Under Xi Jinping,” focuses on the Chinese regime’s policies toward seven major religious groups in China. More than a third of the estimated 350 million religious believers face severe or very severe persecution, which includes “harsh penalties, long prison terms, and deadly violence.”

In some cases, the Party’s eliminationist policies have simply not worked. “The survival of groups and beliefs that the party has invested tremendous resources to crush represents a remarkable failure of the government’s repression,” Cook said, in a press release.

In the prolonged struggle for the spirit of China, “an unreformed Communist Party will ultimately lose,” she said.

Amnesty International researcher William Nee concurred with Freedom House’s core findings of religious control in China, as well as the general trajectories for individual religions.

Within the same denomination, some groups—the Hui Muslims, for instance—are treated leniently, while others—like the Uyghurs—are dealt with harshly. Repression of Christians has been stepped up in the wealthy coastal province of Zhejiang, but not elsewhere.

The Chinese regime’s contradictory approach towards religion might be due to its perception of what threatens its rule, a perception that shifts according to geopolitical trends, Nee said in an email. “It seems that the Party is very fearful of its ‘ideological security’ and is seeing threats in unlikely places.”

A grandfatherly imam of Uyghur extraction in the province of Xinjiang, for instance, may not seem to fit the standard profile of a political threat. Yet Zubayra Shamseden, the imam’s granddaughter and a coordinator with the Uyghur Human Rights Project, noted that he has been isolated from his community, children, and grandchildren by the local authorities, simply for keeping his faith.

“Religion is part of our identity,” Shamseden said, at the launch of the report in Washington on Feb. 28. “Uyghurs have struggled to retain their religion, culture, and language. ... Without those, we are a lost people—extinct.”

Andrew Jacobs, former Beijing correspondent for The New York Times, said at the report launch that he had been to Xinjiang several times and had witnessed a “shocking level of repression”: Students were forced to eat during the fasting month of Ramadan; anyone who refused to shave his beard was sent to jail; and Uyghurs were stopped on the streets at random for cellphone inspections.

“Fear is palpable and the security apparatus thick and visible,” he added.

Jacobs was most surprised by Freedom House’s findings on Falun Gong, a traditional practice of meditative exercises and teachings based on the principles of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance that was targeted for elimination in 1999. The Freedom House report notes the distinct failure of the elimination campaign, into which the regime has poured extraordinary political and material capital. Now, though the policy is still in place and persecution persists, the intensity of the campaign has somewhat lessened.

“Never thought I'd see a let up,” Jacobs said, noting that Falun Gong is a taboo subject for journalists and that practitioners don’t readily reveal their faith. “To see that there is a relenting is amazing.”

“The way Falun Gong is treated is horrifying,” he added. Practitioners are tortured to give up their faith, and if they refuse, they are “beaten more harshly.”

Carolyn Bartholomew, chair of the U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission, read the report’s section on organ harvesting from Uyghurs, Tibetans, and Falun Gong practitioners—the first mention of such abuses by the Chinese regime in a human rights report by a major NGO.

Disturbed by the regime’s routine blood testing of prisoners of conscience, a necessary step for organ harvesting, Bartholomew, who hosted the report’s launch panel, searched online to see if the routine was carried out elsewhere in the world, but found no parallels.

Bartholomew and the other panelists advocate the use of the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act—new legislation that sanctions human rights abusers and corrupt officials—to deter further religious repression in China. “It’s like killing the chickens to scare the monkeys,” Bartholomew said, re-appropriating an expression that Chinese authorities often use.

“Despite this huge machine of repression, religious practice continues to flourish,” Jacobs said. “The government is winning battles, but not the overall war.”

“And if they can’t extinguish religion now with all the tools they have, then when?” he said.