Many people delight in the spectacle of wax museums. Others cringe and feel uneasy around the unmoving, but uncannily lifelike figures. Wax museums, sometimes called waxworks, display collections of wax sculptures molded to portray historical figures, royalty, celebrities, and other notable individuals. Some museums will feature a “Chamber of Horrors,” showcasing heinous criminals or undead terrors. Modern techniques and advanced artistry lends the wax figures a hyper-reality that can be off-putting to some, astounding to others.

However, the history of the most famous waxworks of them all—Madame Tussauds Wax Museum in London, is a dark one. Tussaud’s story of art, death, revolution, and fame remains hidden beneath the modern museum’s public-friendly exterior. The history of Madam Tussauds is a tale of gruesome masks, bloody revolution, and one of the 19th century’s most successful business women.

Molding Heads and Carving Faces

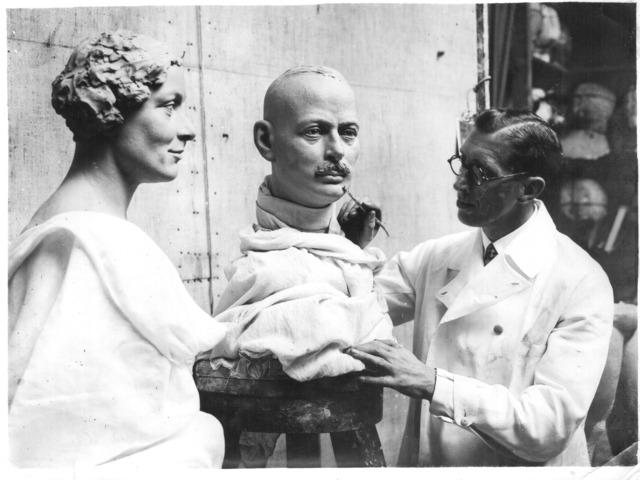

Born in France in 1761, a young Marie Grosholtz was raised by her widowed mother—her father, a German soldier, having died of gruesome war wounds. The two moved to Switzerland where Marie’s mother was housekeeper for Philippe Curtius, a skilled physician. Curtius taught Grosholtz the art of wax sculpture. HistoryToday writes that Curtius had a talent for wax modelling and amassed his own collection of wax heads and busts.

Grosholtz was adept at waxworks, and sculpted notable figures of the day, including historian and philosopher Francois Voltarie, and statesman Benjamin Franklin.