The answer from Russia’s foreign ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova was blunt. Asked on Nov. 3 if saving Syria’s president, Bashar al-Assad, was a matter of principle for the Russians, Zakharova replied: “Absolutely not, we never said that.”

Driving home the point, she added: “We are not saying that Assad should leave or stay,” declaring that it was up to the Syrian people to decide his fate.

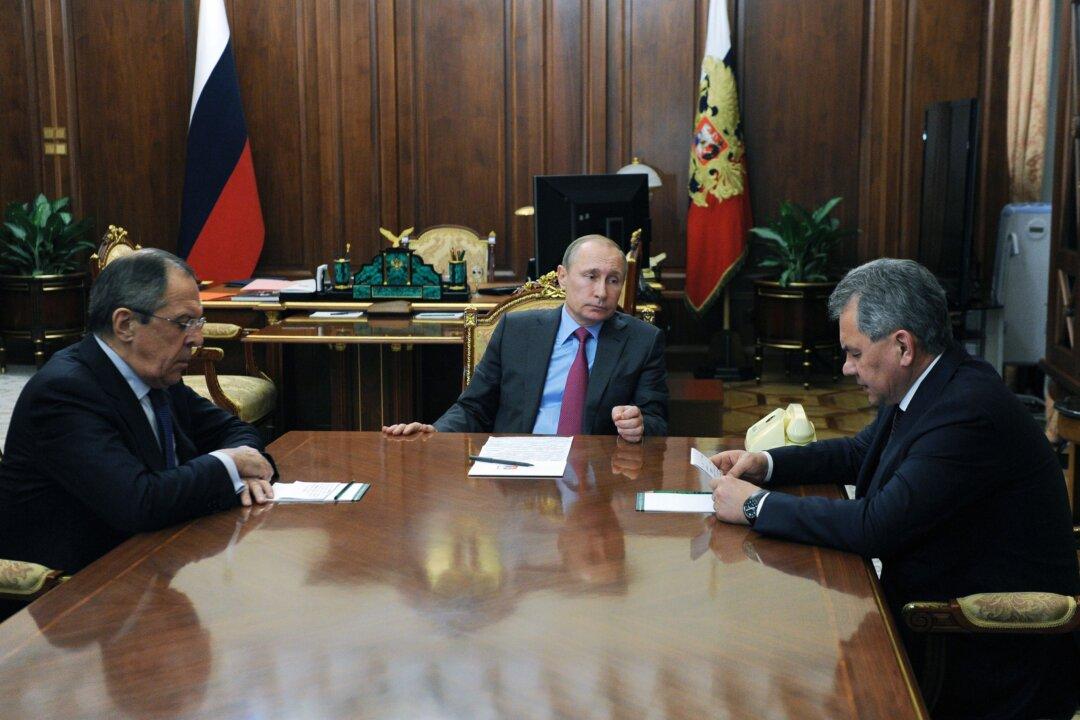

In October, Russia began bombing rebel positions inside Syria, as well as the Islamic State, to prop up an Assad regime facing military defeat. At the end of the month, Moscow’s efforts for an international conference to confirm Assad’s short-term hold on power produced a meeting in Vienna.

Russia is having to rethink its approach because its political-military strategy to prop up the Assad regime has not been successful.