Russian President Vladimir Putin is not an easy politician to read. He is willing to say one thing while his diplomats and military do another—as the long-running conflict in Ukraine has demonstrated. His statements are at the pinnacle of a Russian state propaganda machine shrouding any “truth” in layers of often deceptive assertions.

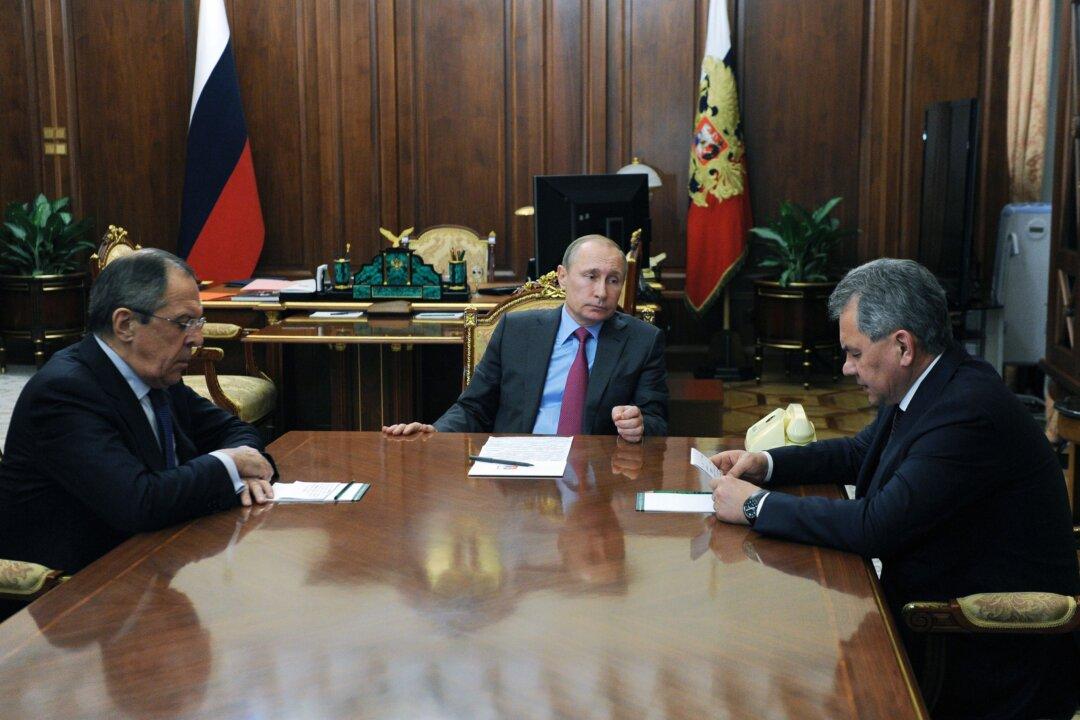

And, as the announcement on March 14 of a “withdrawal of most of [Russia’s] military group” from Syria demonstrated, he can spring a surprise on both his allies and his foes.

So, does this represent mission accomplished for Putin—as he maintained on Monday (“the tasks … are generally fulfilled”), or is this a sign of Russian weakness, with the costs of military intervention compounded by a shaky economy, the challenge of sanctions on Moscow, and a sharp fall in oil revenues?

Or is Putin just being deceptive, with his air force ready to resume bombing and his advisers ready to support pro-Assad ground offensives—especially if political talks to resolve Syria’s five-year conflict fail in Geneva?

Russia’s Short-Term Goal

The starting point is that Russia’s launch of a massive bombing campaign on Sept. 30 had an immediate objective, rather than a long-term vision. Moscow and Iran, Assad’s other main ally, had agreed in late July that intervention was necessary to prevent the defeat of the regime. They resolved to hold a defense line from the Mediterranean via Syria’s third city Homs to the capital Damascus.

The chief threat to the Syrian military was the rebel blocs which had taken much of the northwest—including Idlib Province—and the south. Those forces were on the verge of advancing on the city of Hama and possibly breaking through in Syria’s largest city Aleppo, divided since 2012.