In 1934, two physicists came up with a theory that described how to create matter from pure light. But they dismissed the idea of ever observing such a phenomenon in the laboratory because of the difficulties involved setting up such an experiment.

Now, Oliver Pike of Imperial College London and his colleagues have found a way to achieve this dream, 80 years after US physicists Gregory Breit and John Wheeler explained the theory. This group hopes to use high-energy lasers aimed at a specially designed gold vessel to convert photons into matter-antimatter particle pairs, recreating what happens in some exceptional stellar explosions.

Pike, who led the research published in the journal Nature Photonics, said, “The idea is that light goes in and matter comes out.” To be sure, the matter created won’t be every day-objects; instead the process will produce sub-atomic particles.

“To start with, the matter will consist of electrons and its antimatter equivalent positrons,” Pike said. “But with higher energy input in the lasers, we should be able to create heavier particles.”

Pike concedes this won’t be the first time light has been converted into matter. In 1997, US researchers at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Centre (SLAC) were able to do so, albeit in a different way.

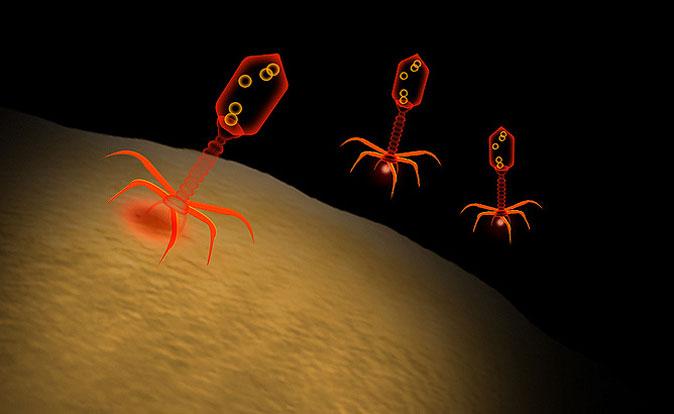

The SLAC experiment used electrons to first create high-energy light particles, which then underwent multiple collisions to produce electrons and positrons, all within same chamber. This is called the multi-photon Breit-Wheeler process, named after the two physicists who came up with the theory in 1934.

“The key difference in the SLAC experiment and the one we propose is that our process will be more straightforward,” Pike said. In the new proposal, the laser beam will still be generated using free electrons, but it will be separated from the electrons.

Why create light using matter and then convert it back? Apart from showing that the Breit-Wheeler process can happen without the multiple photons the SLAC experiment needed, Pike thinks their process provides a clean way of doing particle physics experiments.

Current particle-physics experiments involve smashing sub-atomic particles at great speeds and sorting through the mess of new particles that are created in the explosion. This is how the Higgs boson was found in the Large Hadron Collider.

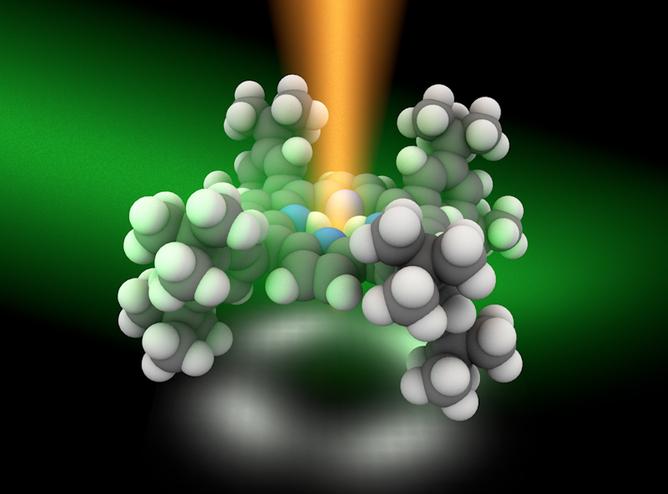

The new experimental design will be similar. Rather than involving a complicated mix of particles and photons, the laser beam will be sent into a small gold hohlraum (German for “empty room”). There, individual photons can interact with the radiation field that’s generated when the hohlraum is excited by a laser, creating the electron-positron pairs.

“While physicists have excellent methods to sift through such data, our process has the advantage that it will be easier to analyse,” Pike said. “Light will go in from one end of the hohlraum and particles created will come out from the other end.”

Pike and colleagues are now working to secure time on high-energy laser beams to carry out the experiment. The two likely candidates are Aldermaston, Berkshire in the UK or Rochester, New York in the US.

Andrei Seryi at the University of Oxford found the work interesting, but warned it is still too far away from being used in particle-physics experiments. “Theoretically, however, it would be great if we are able to create particles from only light.”

“With such high energy lasers, we may not need to build big particle colliders, such as the Large Hadron Collider, which is a 22km underground tunnel,” Seryi said.

Even if we do manage to create a photon collider, we would only be catching up with the natural world, where a specific type of supernova, called “pair instability,” involves the creation of proton-antiproton pairs. If Pike is able to achieve this phenomenon, he will essentially be creating a supernova in a bottle.

Akshat has a PhD in organic chemistry from Oxford University as well as a Bachelor of Technology in chemical engineering from the Institute of Chemical Technology in Mumbai. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

*Image of “light beam“ via Shutterstock