‘Study Drugs’ Unsafe and Unethical, Say Neurologists

‘Study drugs’ are touted to give students a competitive edge, but experts advise it could lead to big health problems.

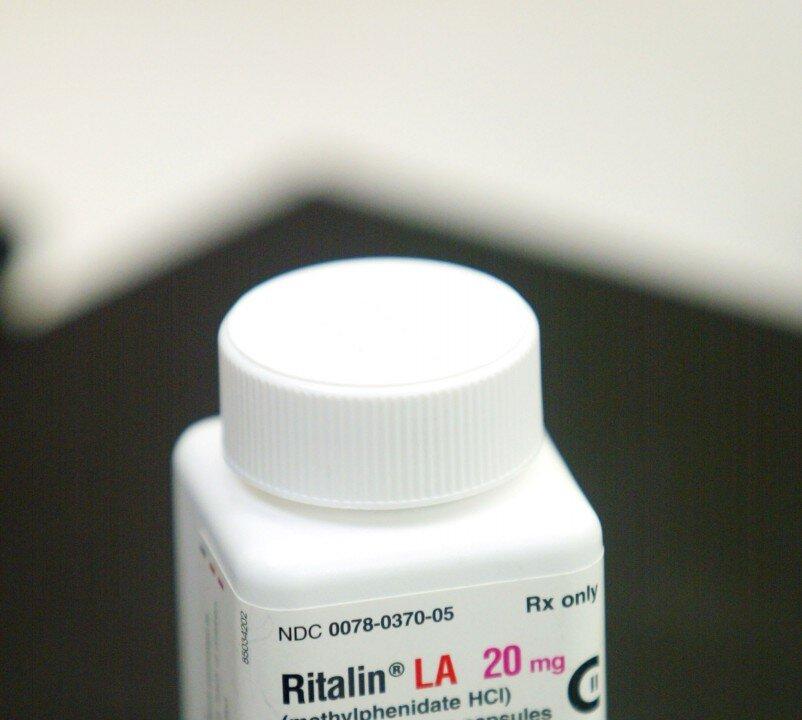

Methylphenidate (better known as Ritalin) was approved for child hyperactivity in 1961, but starting in the 1990s, prescriptions for Ritalin and other amphetamines soared. While they are intended to treat severe attention deficit, many children use them as study drugs. Joe Raedle/Getty Images

|Updated: