The “Standards for Being a Good Student and Child” (Di Zi Gui) is a traditional Chinese textbook for children that teaches children morals and proper etiquette. It was written by Li Yuxiu in the Qing Dynasty, during the reign of Emperor Kang Xi (1661-1722). In this series, we present some ancient Chinese stories that exemplify the valuable lessons taught in the Di Zi Gui. The first chapter of the Di Zi Gui introduces the Chinese concept of xiao, or filial duty to one’s parents.

Min Ziqian’s filial piety touches his contemptuous stepmother

Regarding filial piety, The Di Zi Gui states:

If my parents love me,

Being filial is no difficulty.

If they disdain me,

My filial piety is truly noble.

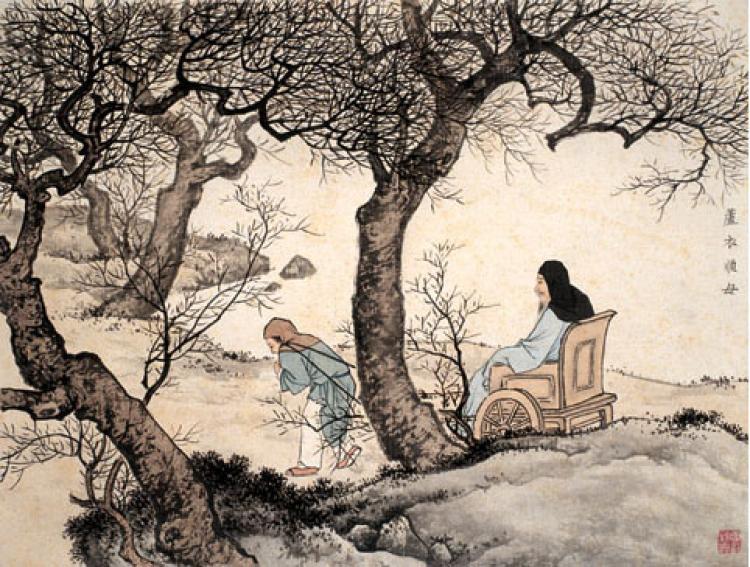

A moral exemplar of filial piety, or respect for one’s parents, is Min Ziqian from the Spring-Autumn period. Min Ziqian lived in the country of Lu during the Spring-Autumn period (770 B.C–476 B.C). When he was young, he lost his birth mother but his father remarried and had two children with his stepmother.

Min Ziqian respected and cared about both his father and stepmother but his stepmother disliked him. One winter, she made warm winter jackets for her two sons but made Min Ziqian a jacket using the flocculent part from reed which appears cotton-like but doesn’t maintain heat.

It was a severe winter and one day Min Ziqian’s father asked him to drive the carriage, but Min Ziqian could barely hold the halter because he was freezing cold. His dad became very upset with him but Min Ziqian didn’t say a word. Min Ziqian’s father later noticed that his son looked really pale. He touched him and noticed that Min Ziqian was only wearing a thin jacket.

He took off Min Ziqian’s jacket and saw that the jacket was only made of reed, but his other two sons were wearing warm cotton jackets. His father was displeased and decided to divorce his wife for her cruelty. But Min Ziqian burst into tears crying, “With mother in the family, only one child suffers coldness. Should she be gone, all three of your sons would freeze.”

Hearing what Min Ziqian had said, Min Ziqian’s step-mother was deeply touched and started to care for all three sons fairly.

The story of Min Ziqian’s filial piety has been spread widely since.

The importance of sincerely correcting one’s mistakes

The Di Zi Gui states:

A error made by accident

Is called a mistake.

An error made by design

Is called evil.Mistakes can be corrected

And yourself redeemed;

But hiding your actions

Adds yet a crime to the deed.

When something is wrong, we need to analyse whether the error was intentional or due to carelessness. In addition, we should not cover it up or find an excuse, but we should sincerely correct the error.

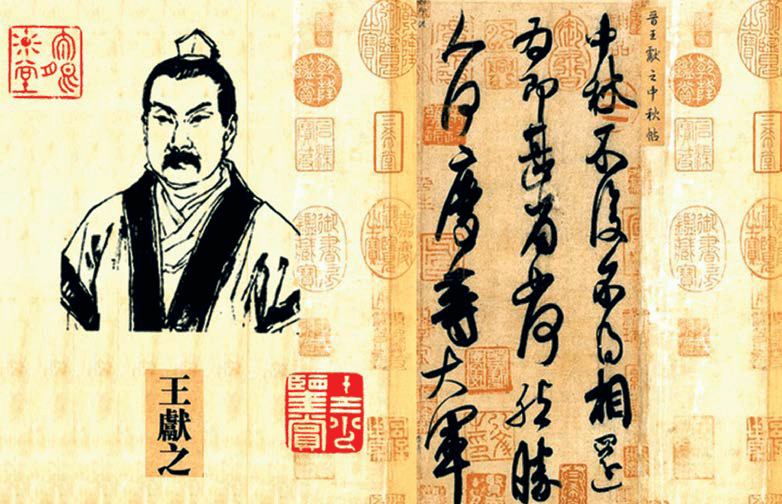

The famous Chinese literary giant, Zeng Gong, had a close friendship with Wang Anshi in the Song Dynasty. One day, Emperor Shen Zong asked Zeng Gong: “What do you think of Anshi’s personality?”

Zeng Gong answered: “Anshi’s writing is as good as that of Yang Xiong in the Han Dynasty. However, because he is stingy, he is not as good as Yang Xiong!”

The emperor said: “Anshi doesn’t care too much about fame and money, so why do you say that he is stingy?”

Zeng Gong replied: “What I mean by ’stingy' is that Anshi isn’t willing to correct his mistakes even though he is aggressive and has achievements.” The emperor heard his words and nodded his head to show agreement.

Wang Anshi was famous because of his talents and knowledge. However, he was stubborn and never admitted any wrongdoing. When enforcing new legislation, he eventually harmed people and was left with a bad name in history.

From ancient times to now, the great sages were not people who didn’t make mistakes. Rather, they made mistakes, but they corrected them quickly. They often examined themselves and criticized themselves appropriately.

As aptly put by in the ancient Chinese saying, “Being able to correct (one’s) mistakes is the greatest thing that nothing else can compare with.”

Do not pursue or indulge in vanity

The Di Zi Gui states that we must not act in any way that is wrong or unfair to others, even if we think that the act is trivial and bears little or no consequence. Our parents would not want to see us doing things that are immoral or illegal. The classic also states that we should not keep any secrets from our parents, however insignificant the secret may be, because it will hurt our parents’ feelings if we do.

Though the matter be small,

Do not handle it whimsically.

Handling it whimsically

Harms the code you follow.Though the thing be small,

Do not keep it to yourself.

Keeping it to yourself,

Brings sadness to your parents.

In ancient times, parents were strict in applying these standards and rules to their children, with corresponding disciplinary action. This nurtured many children to become formidable generals without fear of death. Under the guidance of their righteous parents, they became honest officers in China’s many dynasties, serving their people and country without seeking any returns for themselves or their families.

One such example is the story of the Ming Dynasty general Qi Jiguang, and his father, Qi Jingtong.

Qi Jiguang was born into a military family. At the time Jiguang was born, his father, Qi Jingtong, was at the relatively old age of 56. Jiguang was the only son in the family and his father loved him dearly. He personally taught Qi Jiguang to read books and to practice martial arts. However, he was very strict with Jiguang’s moral character and conduct.

One day, when Qi Jiguang was 13, he received a pair of well-made silk shoes. Walking back and forth in the courtyard in his new shoes, he felt very pleased with them. But Jiguang was seen by his father, who then called him into the study and scolded him angrily, “Once you have good shoes, you will naturally dream about wearing good clothes. Once you have good clothes, you will naturally dream about eating good food. At such a young age, you have developed the mentality of enjoying good food and good clothing. You will have insatiable greed in the future.”