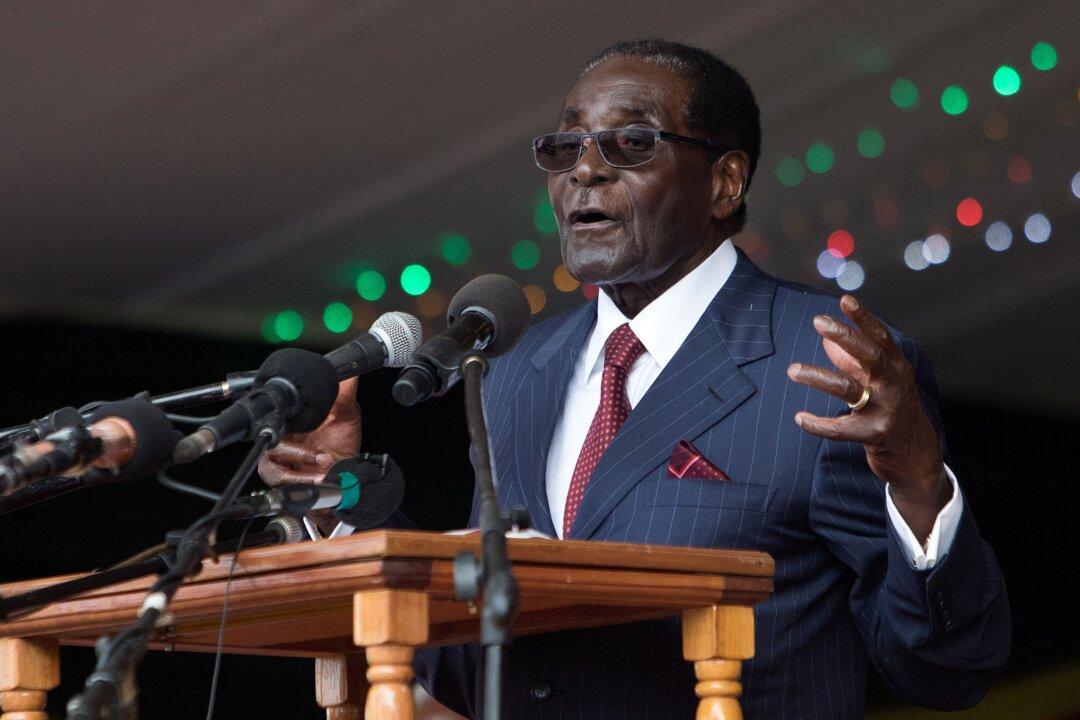

In some ways, South Africa’s president, Jacob Zuma, must be exceptionally happy about the #Rhodesmustfall campaign. After all, it takes the heat off him and puts it on a dead white man—or rather, a block of stone in the likeness of a dead white man.

I went to Rhodes’s grave in the Matopos Hills in Zimbabwe in 1980. These are the most beautiful landscapes in Africa—and the spiritual power accorded the region by the Ndbelele people was palpable. On the grave, a flat slab at ground level, huge rainbow lizards danced. It seemed prophetic: one day, there would be a rainbow nation that would be able to make light of the tragic restrictions of the past.

Zuma administration has carelessly and wantonly frittered away the last traces of South Africa's rainbow of equity and its promise of economic equality.