As British politics descended into a post-EU referendum melee of opportunism, betrayal, resignations, and votes of no confidence, the U.K. was in no position to lecture others on good governance. Fitting then, perhaps, that it received a rare visit from one of the world’s more benighted regimes.

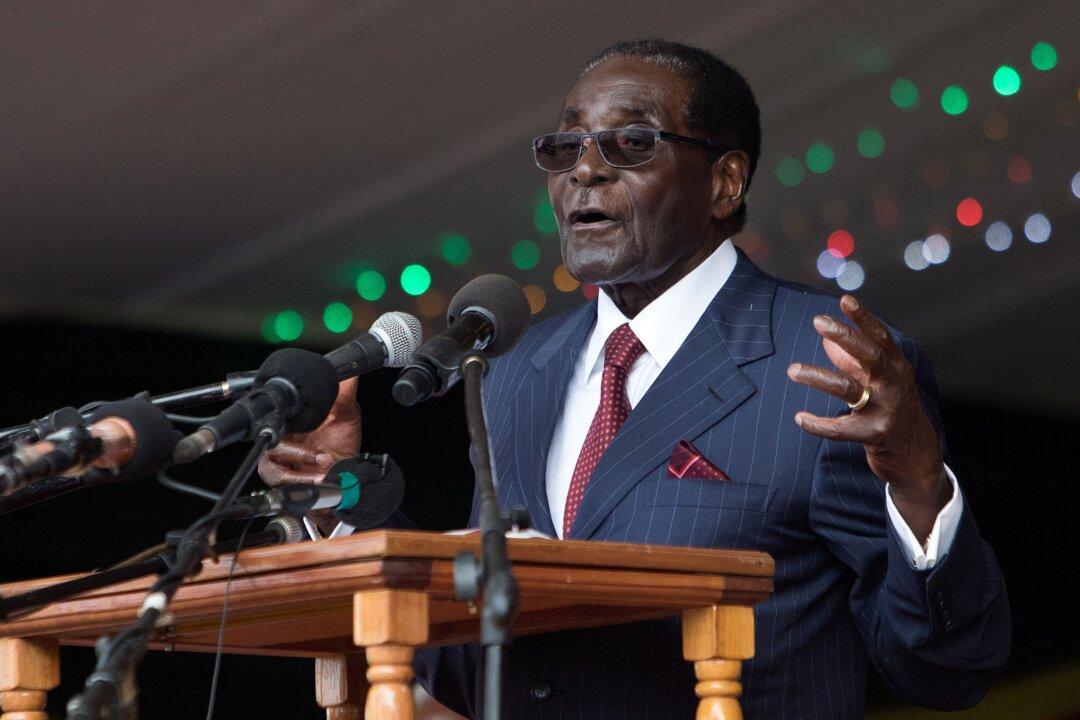

A delegation of senior ministers from the Zimbabwean government came to London. It was led by Robert Mugabe’s finance minister, Patrick Chinamasa, who’s proven to be good at his job inasmuch as he’s conducting himself with decorum in an impossible situation.

Zimbabwe has no money, and its government has no fiscal plan. Its reserves are emptied, tax revenues are inadequate, public funds are still ransacked, and much of the country’s remaining formal employment is in an unproductive public service. Doctors, nurses, and teachers are striking over unpaid wages, and their protests are turning into violent clashes with police. Foreign governments are not helping with standby budgetary support, and foreign corporations are not keen to invest in such a volatile country.

Part of that volatility is because of the power struggle now engulfing the ruling party. One of its wings, led by liberation war hero Joice Mujuru, has been entirely purged. The vice-president, Emerson Mnangagwa, is under heavy fire from a pro-Mugabe faction calling itself the Group of 40 (G40)—a younger group who are not in their 70s, as is Mnangagwa, and certainly not in their 90s, as is Mugabe. Their talisman is Mugabe’s wife, Grace.

The G40’s members may be young enough not to have fought in the liberation war, but their announcements are still steeped in liberation rhetoric. That may or may not help it take control, but it has nothing to do with good governance. For all its influence over the party, the G40 has no plausible plan to address the problems Chinamasa and Zimbabwe face.

What is left of the opposition, meanwhile, is deeply divided, and its longtime leader, the charismatic Morgan Tsvangirai, has cancer.

And while opposition figure Tendai Biti, a successful finance minister during the coalition government of 2009–2013, came to London with Chinamasa, he has little to offer. His plans require a political accommodation with the West, and he surely knows that investment will only be prompted by an embrace of political pragmatism—something in short supply in Mugabe’s Zimbabwe.

Nationalism Placated

Few of London’s heavyweight business figures came to listen to Chinamasa’s pitch, and for good reason. Apart from Zimbabwe’s deeply uninviting atmosphere of political and economic volatility, there is its rigid “indigenization“ legislation, which requires that all companies operating in the country must be majority-owned by indigenous Zimbabweans. Few foreign companies will invest the billions of dollars Zimbabwe needs only to be shorn of their assets just like that.

President Mugabe has assured the outside world that reasonable accommodations will be made, and that pragmatism will rule. But Chinamasa will know, as will every corporation’s legal team, that large investment is not forthcoming without legal protections, and courts of law that can be counted on to uphold them.