An ancient fiber could soon be spun into cutting edge technology. Recent discoveries and new processing techniques have shown that silk can offer innovative solutions in medicine and electronics.

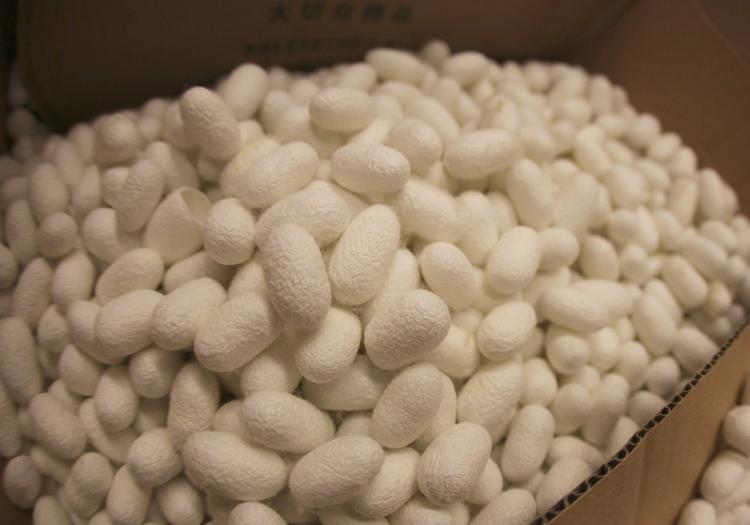

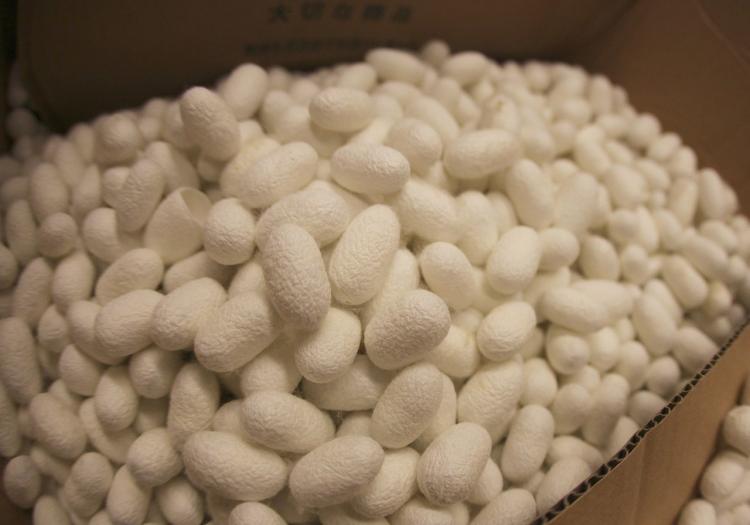

For centuries, silk has been celebrated for both its durability and delicacy. However, this fiber—made largely from the cocoons of the mulberry silkworm, Bombyx mori—hasn’t seen much use outside of thread and textiles. Today, using biocompatible green processing, scientists have found that silk cocoons can yield a pure protein with numerous applications.

For example, researchers have developed a silk card with diffractive optics made entirely of pure silk. Pouring a silk solution on nanopatterned molds and letting the solution dry and crystallize produces a film that retains a pattern. The result is a free-standing optical component so flexible it can be rolled up.

Even more incredible, these translucent membranes can even be safely consumed. Known as edible optics, researchers say these silk-based sensors could soon be used on food to warn consumers of possible bacterial contamination.

“Silk-based materials have been transformed in just the past decade from the commodity textile world to a growing web of applications in more high technology directions,” report Tufts biomedical engineering researchers Fiorenzo Omenetto, Ph.D., and David Kaplan, Ph.D. in the July 30 issue of the journal Science.

In their recent publication, Kaplan and Omenetto explain that the development of silk hydrogels, films, fibers, and sponges is paving the way for advances in photonics and optics, nanotechnology, electronics, adhesives, microfluidics, and even the engineering of silken bone and ligaments.

Silk sees its earliest roots in ancient China where silk garments were once reserved solely for royalty. The textiles made from silk are not only luxurious, but extremely durable. Today scientists have found that the silk spun by spiders and silk worms combines high strength and extensibility—attributes that synthetics just can’t match.

But it isn’t just strength and durability that make silk so sought-after. Because silk fiber formation does not rely on complex or toxic chemistries, such materials are biologically and environmentally friendly. The technology developed from silk can even be integrated with living systems.

Kaplan and Omenetto believe applications could soon include degradable and flexible electronic displays for sensors that are biologically and environmentally compatible, as well as implantable optical systems for diagnosis and treatment.

Progress in edible optics and implantable electronics has already been demonstrated by Kaplan and Omenetto, John Rogers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and others.

As scientists begin to unravel the mystery of how these simple protein-based fibers are produced they find that chemistry, molecular biology, and biophysics all play a role in developing the silken strands.

However, Kaplan and Omenetto admit that researchers are still struggling with how to fully replicate native silk assembly in the lab, how best to mimic silk protein sequences via genetic engineering to scale-up materials production, and how to use silk as a model polymer to spur new synthetic polymer designs that mimic natural silk’s green chemistry.

Meanwhile, researchers are developing techniques for reprocessing natural silk protein in the lab. Silks are also being cloned and expressed in a variety of hosts, including E. coli bacteria, fungi, plants and mammals, and through transgenic silkworms.

“Based on the recent and rapid progression of silk materials from the ancient textile use into a host of new high-technology applications, we anticipate growth in the use of silks in a wide platform of applications will continue as answers to these remaining questions are obtained,” said Omenetto and Kaplan in a statement.

For centuries, silk has been celebrated for both its durability and delicacy. However, this fiber—made largely from the cocoons of the mulberry silkworm, Bombyx mori—hasn’t seen much use outside of thread and textiles. Today, using biocompatible green processing, scientists have found that silk cocoons can yield a pure protein with numerous applications.

For example, researchers have developed a silk card with diffractive optics made entirely of pure silk. Pouring a silk solution on nanopatterned molds and letting the solution dry and crystallize produces a film that retains a pattern. The result is a free-standing optical component so flexible it can be rolled up.

Even more incredible, these translucent membranes can even be safely consumed. Known as edible optics, researchers say these silk-based sensors could soon be used on food to warn consumers of possible bacterial contamination.

“Silk-based materials have been transformed in just the past decade from the commodity textile world to a growing web of applications in more high technology directions,” report Tufts biomedical engineering researchers Fiorenzo Omenetto, Ph.D., and David Kaplan, Ph.D. in the July 30 issue of the journal Science.

In their recent publication, Kaplan and Omenetto explain that the development of silk hydrogels, films, fibers, and sponges is paving the way for advances in photonics and optics, nanotechnology, electronics, adhesives, microfluidics, and even the engineering of silken bone and ligaments.

Silk sees its earliest roots in ancient China where silk garments were once reserved solely for royalty. The textiles made from silk are not only luxurious, but extremely durable. Today scientists have found that the silk spun by spiders and silk worms combines high strength and extensibility—attributes that synthetics just can’t match.

But it isn’t just strength and durability that make silk so sought-after. Because silk fiber formation does not rely on complex or toxic chemistries, such materials are biologically and environmentally friendly. The technology developed from silk can even be integrated with living systems.

Kaplan and Omenetto believe applications could soon include degradable and flexible electronic displays for sensors that are biologically and environmentally compatible, as well as implantable optical systems for diagnosis and treatment.

Progress in edible optics and implantable electronics has already been demonstrated by Kaplan and Omenetto, John Rogers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and others.

As scientists begin to unravel the mystery of how these simple protein-based fibers are produced they find that chemistry, molecular biology, and biophysics all play a role in developing the silken strands.

However, Kaplan and Omenetto admit that researchers are still struggling with how to fully replicate native silk assembly in the lab, how best to mimic silk protein sequences via genetic engineering to scale-up materials production, and how to use silk as a model polymer to spur new synthetic polymer designs that mimic natural silk’s green chemistry.

Meanwhile, researchers are developing techniques for reprocessing natural silk protein in the lab. Silks are also being cloned and expressed in a variety of hosts, including E. coli bacteria, fungi, plants and mammals, and through transgenic silkworms.

“Based on the recent and rapid progression of silk materials from the ancient textile use into a host of new high-technology applications, we anticipate growth in the use of silks in a wide platform of applications will continue as answers to these remaining questions are obtained,” said Omenetto and Kaplan in a statement.