Our discussion of Hong Kong independence is limited and purely academic, says a local student publication, but it is our Chief Executive who is really promoting it.

In the latest issue of Hong Kong University Students’ Union’s magazine Undergrad, deputy editor Chan Ah Ming addressed Hong Kong leader Leung Chun-ying’s accusation that the publication is promoting self-determination.

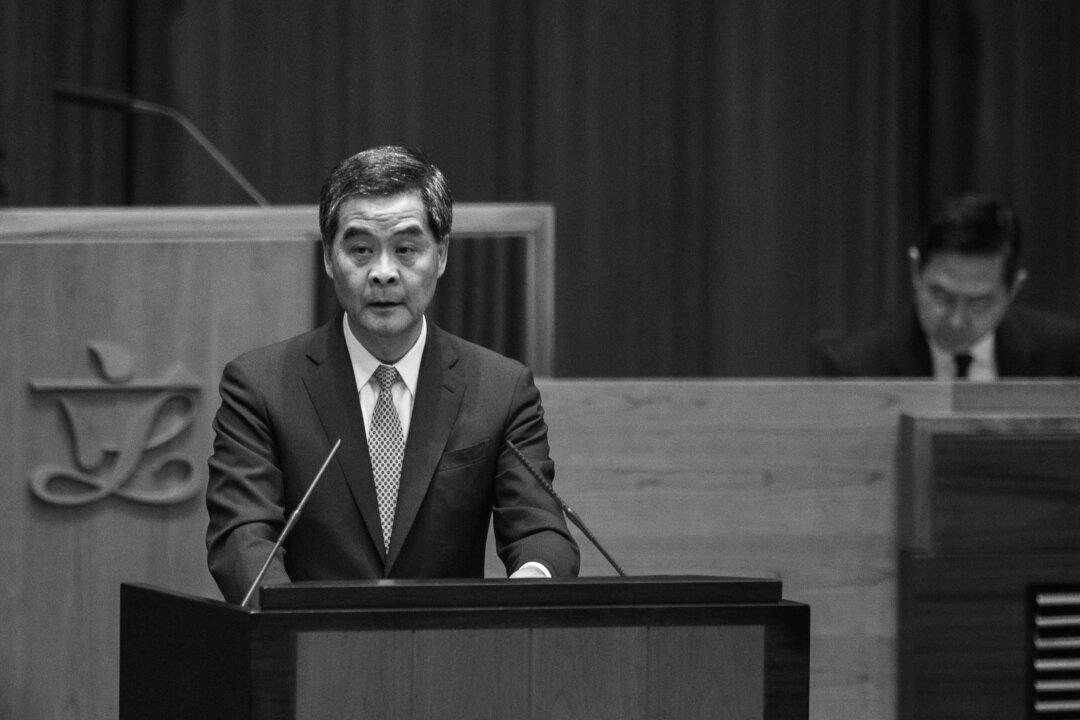

In his third policy address on Jan. 14, the Chief Executive—better known by locals as “CY Leung”—censured a 2013 issue of the Undergrad, then a largely unnoticed monthly student title.

“The issue concerning the independence of Hong Kong,” said Leung “is not a [matter of] ordinary academic research or discussion.”

“It is indeed advocacy, and we should not take it as a trivial matter,” Leung continued.

Because certain words and slogans used by protesters during the almost three-month long Occupy protests supposedly promotes self-reliance, Leung also suggested that lawmakers close to the Umbrella Movement student leaders should “advise them against putting forward such fallacies.”

Hong Kong was returned to mainland China in 1997 under a “one country, two systems” principle. The Chinese financial hub is allowed a “high degree of autonomy” to rule itself, according to the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration, and can keep its economy, legal system, and all rights and freedoms until 2047.

Leung’s criticism of the Undergrad—a last-minute addition to his policy address—was slammed by pro-democracy lawmakers as an attack on the youth and freedom of speech.

“Are you trying to stir up a Cultural Revolution in Hong Kong,” Labor Party chairman Lee Cheuk-yan asked Leung, referencing a tumultuous decade of political purges and destruction of tradition in China by the Communist regime.

“Are those criticisms your only reflection on the youth issue after the Umbrella Movement,” said Lee. “Are you trying to suppress freedom of speech until ‘one country, two systems’ is destroyed?”

Youth ‘Problems’

Chan Ah Ming echoed Lee’s criticism of Leung in the January 2015 issue of the Undergrad.

Instead of “mending bridges with the Umbrella generation after the Occupy protests,” says Chan, Leung intents to solve Hong Kong’s “youth problem”—increasingly vocal youths taking up pro-democracy activism—by “suppressing” and “chasing” away youths.

Examples of the Chief Executive’s marginalization of the youth include the Cultural Revolution-style denouncement of the Undergrad during his policy address and encouragement of Hong Kong’s youths to leave the city for work.

“When there are no youths in Hong Kong,” Chan continues, “there won’t be a youth problem.”

As for Hong Kong independence, Chan claims that the 2013 Undergrad issue was an attempt to separate calls for civic nomination and self-determination because left-leaning newspapers and the Chinese regime were deliberately mixing the two.

If demands for universal suffrage is equated with Hong Kong independence, Chan argues, then the Chinese regime can use that as a pretext to deny Hong Kong residents a free vote in elections, which is guaranteed in the Basic Law, the city’s governing document.

Undergrad’s discussion of Hong Kong independence is also not as controversial as it seems, says Chan. Being an academic student publication, the Undergrad is not expected to be widely read and debated.

Also, the magazine had raised self-reliance in the 1960s, socialism in the 1970s—a contentious idea then—and was critical of the British colonial government.

Chan adds that the idea of Hong Kong independence was not in currency—at least until CY Leung highlighted the Undergrad in his policy address.

Because Leung is in a position of power, Chan argues, his comments have political implications, and is thus responsible for bringing the subject to the mainstream.

Besides, “the Undergrad doesn’t have the resources or ‘foreign aid’ to advocate for Hong Kong independence,“ said Chan, a jibe at the Chief Executive’s claim that ”foreign forces” had interfered with the Umbrella Movement.

‘Conflict Management’

In response to the criticism from the Undergrad, the Chief Executive’s Office stated that CY Leung has a “duty” to let the public know that advocating self-determination is “unconstitutional,” local broadcaster Radio Television Hong Kong reports.

It is also Leung’s duty to defend the country’s “unity and sovereignty,” the CE office claims.

Or it could be an act of self-preservation on the Chief Executive’s part.

Leung might be looking for a way to secure Beijing’s backing and get re-elected in 2017 through “conflict management,” says Alfred Chan (no relation to Chan Ah Ming), vice convener of the Progressive Teachers Alliance, in a telephone interview with Epoch Times.

Chief Executive candidates have to be approved by a small pro-Beijing election committee, and Beijing reserves the final say on who gets to be Hong Kong’s leader. But Leung, who only mustered 689 of 1,200 votes in 2012, is hugely unpopular in Hong Kong, and will unlikely get a second term.

Because most Hong Kong people are happy to be part of China if they have real democracy, and self-determination is an idea that is “taboo,” says Chan, Leung is looking to turn Hongkongers against each other by drawing attention to the Undergrad and making Hong Kong independence seem like a hot issue.

By engineering a conflict and then stepping in to resolve it, Leung can then prove his worth to the Chinese regime and keep his office, says Chan.