News Analysis

The market for private equity (PE) buyouts has largely been stagnant since the recent financial crisis and the subsequent financing freeze. Recent trends are forcing the world’s biggest private equity firms to seek alternative sources of capital and investments.

Investors in private equity funds consist mainly of institutional investors such as government and corporate pension funds, wealthy individuals, and sovereign wealth funds.

Similar to venture capital, private equity firms make investments in companies, which are not publicly traded, to provide capital for growth, turnaround, or new product development. The funds profit by selling the investments at a later time for larger windfall in the form of an IPO or another buyout.

Unlike most venture capital investments, private equity firms undertaking leveraged buyouts typically do not contribute all (or even most) of the necessary capital for the investment, and will raise acquisition debt in the form of bank loans. However, in recent years lenders have cut back on their willingness to extend such credit due to the uncertainty of target companies’ abilities to make interest payments in today’s economic environment.

According to data from Dow Jones LP Source, PE fundraising in the first quarter of 2013, at more than $36 billion, was 12 percent lower than the prior year. That amount includes capital raised by private equity, venture capital, and mezzanine funds.

One of the biggest reasons for lower growth in funding can be traced to a trend over the last two decades of moving away from defined-benefit to defined-contribution pension funds. Today, an increasingly larger number of retirement funds are funneled to accounts self-managed by employees (for example 401(k) accounts), rather than to traditional institutionally managed pensions. Self-managed accounts usually do not have access to alternative investments such as PE funds.

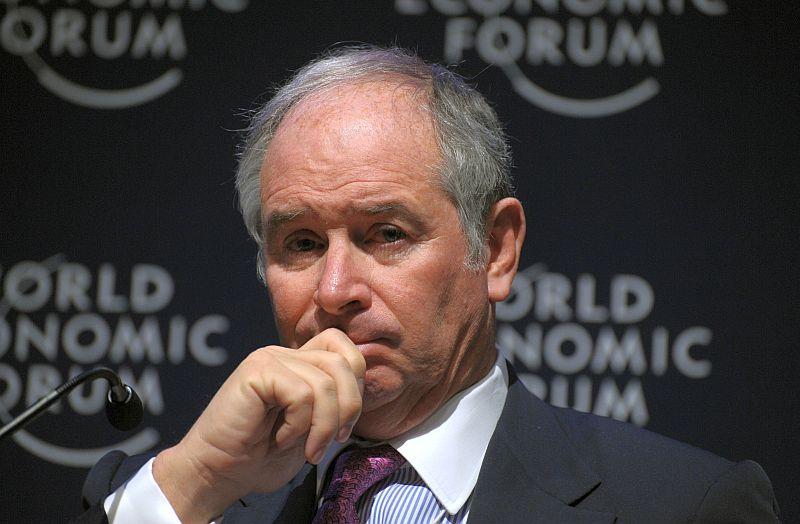

The biggest PE funds (for example Blackstone Group) have moved to partially offset the above effects by purchasing high-interest rate subordinate debt, mezzanine funding, and bridge loans, an area traditionally dominated by hedge funds.

Targeting the Masses

Private equity firms have diversified their fundraising by launching funds that require smaller minimum investments, such as mutual funds and publicly traded funds.

PE funds, with their illiquid holdings and high minimum investments, have traditionally been associated with the wealthy. But by launching mutual funds (with minimums of $2,000) and publicly traded funds (with even lower minimums), the funds now have access to the masses of retail investors.

KKR Asset Management, the hedge fund arm of KKR, launched the KKR Alternative High Yield (KHYLX) mutual fund in November 2012. The fund predominantly invests in high-yield fixed and floating-rate credit products, providing investors with access to the nonpublic high-yield credit market. Blackstone Alternative Asset Management also filed applications last month to commence a new mutual fund.

Ackermans & van Haaren NV (ACKB) is a Belgian trust, which invests in middle-market companies in Europe, including investments in other private equity funds.

TXU Acquisition Dents PE Rep

The 2007 acquisition of Texas power company TXU Corp.—at $45 billion—is the biggest private equity leveraged buyout ever in nominal value. But today it has also become one of the biggest busts and a black eye for the leveraged buyout industry.

TXU, which has subsequently changed its name to Energy Future Holdings Corp., was acquired by TPG Capital, Goldman Sachs Capital Partners, and KKR & Co. (the private equity pioneer formerly known as Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, which famously led the leveraged buyout of RJR Nabisco in 1988) at the height of the leveraged buyout frenzy in 2007 in a club deal. A club deal is an acquisition sponsored by a consortium of private equity firms.

The acquisition was a bet on a rise in natural gas prices. However, an oversupply of natural gas and stabilization of oil prices due to the financial crisis have choked natural gas prices. Natural gas futures are now trading at around $4.14 per Btu—and that’s after a recent rally—compared with $6.88 per Btu at the time of acquisition in 2007. In addition, the buyout left Energy Future Holdings saddled with more than $50 billion in debt, and today, the company is struggling to meet cash flow obligations and is mulling bankruptcy reorganization.

Last week, CreditInsights Inc. estimated that lenders providing financing for the TXU buyout may recover as little as 74 cents on the dollar.

Club Deals Becoming Rarer

The TXU buyout, along with a host of other factors, has made such mega club deals unpopular with private equity firms.

The perception is that the bigger the investment, the more difficult it is to generate returns. The decision-making process also slows down as more firms get involved during the deal cycle. In addition, the large amount of capital tied up in one investment could hamper capital deployment elsewhere in the fund.

“You won’t see as many PE firms teaming up with each other as you did before,” Carlyle Group co-founder David Rubenstein told the audience at a Thomson Reuters conference in Boston earlier this month. “Today, what investors want is to co-invest. They want to go into a fund, but co-invest additional capital—no fee, no carry—and since so many large investors have that interest, they are now going to GPs (general partners) like us and saying ‘If you have a big deal, don’t call up one of your brethren in the private equity world. Call us up.’”

Rubenstein is conveying that wealthy investors are willing to act as co-investors alongside the funds, instead of putting their money in a fund, which generates management fees and carried interest for the fund managers. This cuts costs for investors, but lowers revenue at private equity funds.