The National Football League (NFL) playoffs approach next week. While the league’s popularity, brand power, and immense profitability are undeniable, a vocal minority is challenging the business status of the most powerful sports league in America.

Tickets for upcoming playoff games—not to mention the Super Bowl—cost hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars. While overall television ratings are down due to the advent of Internet streaming, NFL programs have maintained their dominance, accounting for 9 out of the 10 most-watched telecasts of 2013 according to Nielsen data.

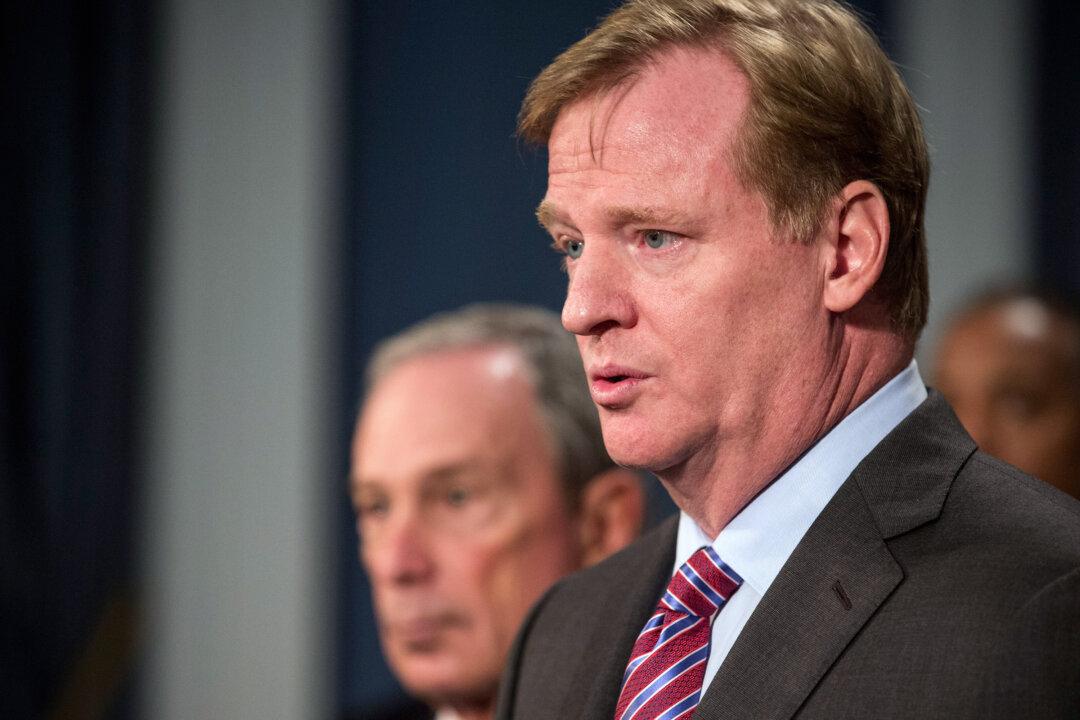

NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell was awarded $29.4 million in compensation in 2012, which is a pay package bigger than many CEOs at Fortune 500 companies.

A little-known fact about the NFL is that despite its business success, the league itself is a tax-exempt entity. And to some, that designation clashes with its identity as a business generating $10 billion in annual revenues.

Challenging its Status

U.S. Sen. Tom Coburn (R-Okla.) in September introduced the PRO Sports Act aiming to amend the tax code to prohibit professional sports organizations with annual revenues greater than $10 million from benefitting from tax-exempt status.

“Working Americans are paying artificially high rates in order to subsidize special breaks for sports leagues,” Coburn said in a statement accompanying the act. “This is hardly fair.”

And it’s becoming a cause that political liberals and conservatives can both support. Activists from Rootstrikers and Change.org have started online petitions in support of taxing the NFL.

“The NFL should pay their fair share toward our economy!” said Lynda Woolard, an activist on Change.org. “Just like Major League Baseball, which gave up its nonprofit status in recent years, as well as the National Basketball Association, the NFL should not be able to hide under a nonprofit status in order to avoid paying federal taxes.”

Structurally Sound

On the surface, it seems absurd to allow tax exemptions for sports leagues promoting athlete millionaires. In addition to the NFL, the National Hockey League (NHL), the PGA Tour, and the ATP World Tour are also tax-exempt.

However, the structure and business operations of such leagues allow for their tax-exempt statuses under the current IRS code. And it’s safe to declare that few elaborate loophole exploits or clever tax schemes are employed.

But before we debate the NFL’s merits as a charity, let’s take a closer look at its business.

The NFL itself is a 501(c)(6) tax-exempt organization, similar to chambers of commerce and other nonprofit boards of trade. In other words, the NFL fashions itself as an organization whose sole function is to further its industry and profession. This is wholly different than the 501(c)(3) designation, which is for charities such as the Red Cross.

There are 32 teams (franchises) in the NFL, each of which pays a fee to the head office (NFL) to cover overhead, including the costs of the commissioner and other officials, activities to administer the games, set rules, and coordinate relationships between team owners, players and other stakeholders. The NFL also administers revenue-sharing agreements between clubs.

The individual NFL teams, such as the New York Giants, are not tax-exempt and pay taxes based on profitability. The NFL’s most recent tax return states that $4.3 billion from TV rights and shared revenues were distributed to teams and such revenues are subject to taxation at the team level.

And that’s not all. Revenues from sponsorships, national merchandising, and the NFL Network fall under a company called NFL Ventures, which is a for-profit corporation that does pay taxes. The NFL has contended in the past that all revenue-making ventures are subject to taxation across a variety of entities.

It appears that under the current construct and the law, the NFL is correct to organize itself as a nonprofit entity and is paying all the taxes as required in its other ventures.

Doesn’t Pass the Smell Test

The actual IRS statute states the following: “IRC 501(c)(6) provides for exemption of business leagues, chambers of commerce, real estate boards, boards of trade, and professional football leagues (whether or not administering a pension fund for football players), which are not organized for profit and no part of the net earnings of which inures to the benefit of any private shareholder or individual.”

So technically, the NFL is a trade association. But technically, McDonald’s Corp. could also bill itself as a trade association promoting the interests of its 15,000 franchises.

NFL teams often enjoy public benefits such as publicly funded stadiums and facilities. The league also acts as a bank and doles out low-interest loans to its franchises, which is eerily similar to below-market bargain loans for the private benefit of insiders. Such activity could be against the spirit of tax-exempt public organizations.

Admittedly, Coburn’s cause is a lonely one. There are just too many political and emotional hurdles to pass such a bill requiring a rewrite of the IRS code. But there are those who continue to push for reforms, especially in today’s environment of corporate social responsibility where being technically correct is no longer good enough.

“If there is a justification for providing tax exemption to business leagues, it would be they operate for the public purpose of aiding commerce for all within a broad segment of some type of business or business in general,” Philip Hackney, a former IRS attorney and current LSU law professor, stated in a USA Today report.

“These (sports) organizations, in my opinion, are anything but public-minded in their profit interest,” Hackney continued.

“They are focused on the profits of their franchises.”

Frank Yu is a contributor to the Epoch Times.