In his diaries, cataloging his time as communications director at Number 10 during the premiership of Tony Blair, Alastair Campbell notes that in the week before the fateful vote on Iraq in March 2003, Rupert Murdoch phoned Blair three times. Campbell writes that Murdoch warned the PM of the dangers of delay and that was he was “pressing on timings, saying how News International would support us etc.”

As we know, that support from the Murdoch press was unwavering and unequivocal. The much maligned editor of the Daily Mail, Paul Dacre, said in written evidence to the Leveson inquiry in 2012 that Murdoch expected his advice to be acted upon:

I don’t think there’s any doubt that he had strong views which he communicated to his editors and expected them to be followed. The classic case is the Iraq War. I’m not sure that the Blair government or Tony Blair would have been able to take the British people to war if it hadn’t been for the implacable support provided by the Murdoch papers. There’s no doubt that came from Mr Murdoch himself.

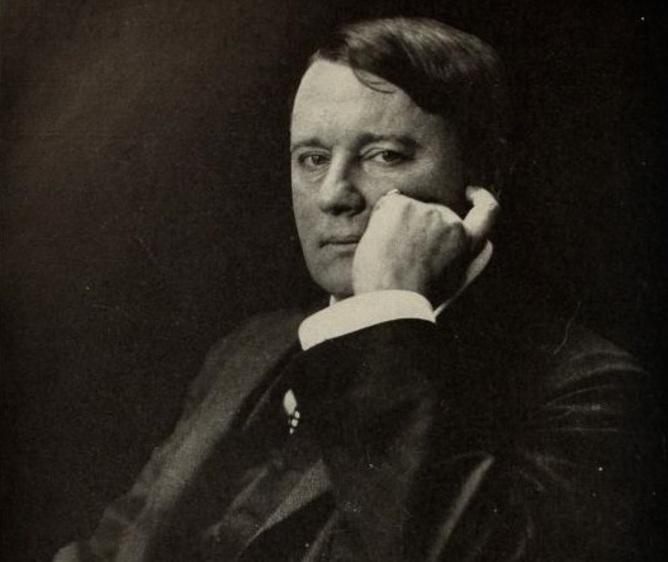

This is all especially interesting to consider as we gear up for the centenary of the U.K.’s entry into World War I. And there’s more than a hint of Murdoch in his counterpart from this period: Alfred Harmsworth, the first Lord Northcliffe.

Press Baron of Old

At World War I’s outbreak, Northcliffe’s position at the forefront of British newspapers was established. He had launched the Daily Mirror and bought and sold the Observer by 1914—by which time he was in control of the Weekly Dispatch, the highest circulation Sunday newspaper, the Times and, most famously, Dacre’s future employer, the Daily Mail. The statistics are enlightening. In 1914 Northcliffe controlled 40 percent of the morning, 45 percent of the evening and 15 percent of the Sunday newspaper circulations. No wonder the politicians of the age sought his approval and support during this most uncertain and unpredictable of times.

And Northcliffe’s influence on government policy during the war is indeed striking. He muscled in on all the major issues of the conflict—from recruitment, to propaganda, to the composition of the cabinet itself. He became, according to historian, Richard Bourne, “a political and national figure … a stalwart of the war effort and a maker and breaker of governments.”

Northcliffe’s political standing at the outbreak of war was very high partly because of his newspapers’ prescience in predicting that war would come. Such was the tone and frequency of anti-German sentiment in the Northcliffe press that some critics were moved to say it contributed to the heightened tensions in Europe which precipitated actual war.

If there was any doubt that Britain should come to the aid of its allies before war was declared on Germany on August 4 1914, then they weren’t articulated in the Northcliffe titles. The Times of July 31 stated:

Our duty is plain. We must make instant preparations to back our friends if they are made the subject of unjust attack … We cannot stand alone in a Europe dominated by any single power.

And the Mail on Aug. 3, the eve of war, was suitably grave:

The shadow of an immense catastrophe broods over Europe today … our duty is to go forward into the valley of the shadow of death with courage and faith—with courage to suffer, with faith in God and our country.

Then came the reduction of the struggle into the simple binary oppositions of good versus evil (to be fair, this was common to the majority of the rest of the media). Germany became the evil hun intent on spreading her pernicious influence across the globe; the Kaiser the devil incarnate. As Phillip Knightley points out, in a single report on September 22 1914 the German King was referred to as a “lunatic,” “barbarian,” “madman,” “monster,” “modern Judas,” and a “criminal monarch.”

The reported deaths of some 5,000 civilians in Germany were seized upon as evidence of collective Teutonic barbarism. The Times of Jan. 8, 1915 stated:

The stories of rape are so horrible in detail that their publication would seem almost impossible were it not for the necessity of showing to the fullest extent the nature of the wild beasts fighting under the German Flag.

Press to Propaganda

In the first years of the war Northcliffe’s primary goal was to galvanize British public opinion in support of total war. But when in 1917 the U.S. entered the fray, prime minister Lloyd George made him head of the British war mission there, evidently hoping that Northcliffe’s skills as a persuader and propagandist would be effective in a country where the anti-war lobby was large and vociferous. His success is open to question. It’s certain that the rosy picture he presented of life at the front line would have seemed ludicrous then, let alone 100 years later. In a 1917 essay for U.S. families of troops he wrote:

At the front, health is so good… The open-air life, the regular and plenteous feeding, the exercise, and the freedom from care and responsibility, keep the soldiers extraordinarily fit and contented.

Northcliffe ended the war as Director of Propaganda in enemy countries. He had direct access to the prime minister. And the close connection between the press and government did not stop there: in 1918 Lord Beaverbrook, later the owner of Express newspapers, was made minister of information, while Robert Donald, editor of the Daily Chronicle, was made director of propaganda in neutral countries.

The job of Northcliffe and his newspapers was to keep the realities of war away from the British public. They were not interested in truth. The prevailing mentality was to make the war seem palatable and righteously necessary.

World War I was the first time people began to realize that newspapers did not necessarily tell the truth. Lieutenant Ulrich Burke of the 2nd Battalion Devonshire Regiment wrote in 1916:

When we did read the newspapers it made us angry… [Y]ou‘d read in the newspapers, ’No action on the Western Front.‘ It didn’t seem to warrant, when you’d lost fifty men killed and an equal number wounded, a mention… It used to annoy everybody terribly.

It seems apposite to end with the now infamous quote from Lloyd George, who in conversation in 1916 with CP Scott, editor of the Manchester Guardian, said:

If the people really knew [the truth] the war would be stopped tomorrow. But of course they don’t know and can’t know.

John Jewell is director of undergraduate studies at the School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies at Cardiff University in the U.K. This article was originally published on The Conversation.