As the premiers gather in Regina from August 5 to 7 for their Council of the Federation summer meeting, a business coalition is urging them to act faster to cut longstanding barriers to interprovincial trade.

The coalition says this would facilitate Canada’s negotiations with the European Union toward a comprehensive economic and trade agreement, the first round of which will take place in October 2009.

“To the extent that we can eliminate these barriers within Canada, we are at a stronger position at the negotiating table to achieve improved access for Canadians [in European markets],” said Ross Laver, vice president of policy and communications of the Canadian Council of Chief Executives, part of the eight-member coalition.

“If we don’t have these issues settled domestically, it’s going to be more difficult to make progress in negotiating with other countries and regions.”

Among the key internal barriers in Canada are policies and regulations that hinder interprovincial trade in goods and those that make it difficult for workers to move between provinces and have their credentials recognized.

Premiers Urged to Act Faster to Cut Interprovincial Trade Barriers

As Canadian premiers gather in Regina August 5 to 7 for a summer meeting, a business coalition is urging them to act faster to cut longstanding barriers to interprovincial trade so they will not hinder Canada’s trade talks with the EU.

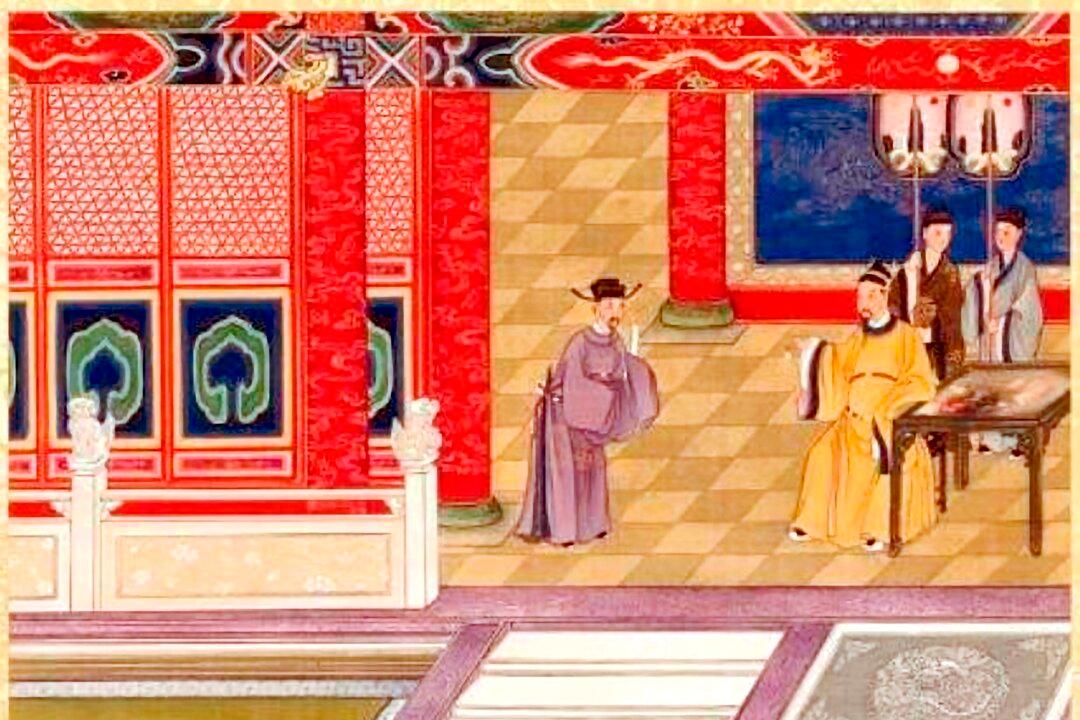

International Trade Minister Stockwell Day and Prime Minister Stephen Harper at the Canada-EU Summit in May 2009 in Prague, Czech Republic, where leaders agreed to launch negotiations toward a Canada-EU comprehensive economic partnership agreement. Government of Canada

|Updated: