Forced abortions in China are not a thing of the past. Under the one child policy, many women in late term pregnancy are still forced to abort their children. Chinese provincial authorities are responsible for mass forced sterilizations, and abortions are often performed by people with inadequate training in unsterile conditions.

“The one child policy causes more violence toward women and girls than any other policy on the face of the earth,” said Reggie Littlejohn, a one child policy expert and president of the newly-founded Women’s Rights Without Frontiers. “Forced abortions and forced sterilizations are an unacceptable form of population control.” She says that when there is free speech in the country people will be able to have a civilized discussion and come up with a solution, though she does not suggest any specific ideas.

Many women develop critical health problems for the rest of their lives and the emotional impact resulting from forced abortions contributes to the high rate of female suicides, she says.

Wei Linrong from Guangxi Province, a devout Christian and anti-abortionist, was forcibly injected with poison that killed her unborn child, according to a National Public Radio (NPR) report. Ten family planning officials visited her home and drove Wei and her husband to a maternity hospital.

Wei was put through nearly 16 hours of contractions before a stillborn emerged, blackened by the effects of drugs. The body was then thrown away like “rubbish” by nurses, according to NPR. Wei was seven months pregnant.

He Caigan, an unmarried 19-year-old, was forced to abort her child at nine months in the same manner, according to the report by NPR. The operation caused her prolonged physical pain and emotional trauma.

The one child policy was introduced in 1979 to curb the apparently growing problem of overpopulation. Years earlier, under Mao Zedong’s rule in the 1950s, Chinese people were encouraged to produce children to boost the country’s labor and military forces.

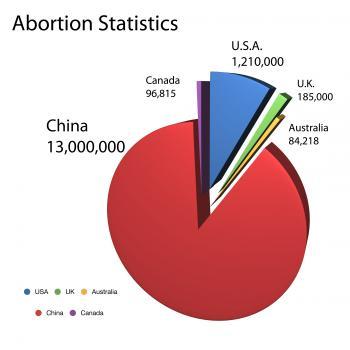

13 Million Abortions a Year

China Daily, a state-controlled newspaper, recently published annual abortion figures of 13 million and a live birth rate of 20 million, as recorded by China’s National Family Planning Commission.

The recent China Daily article, echoed by a BBC report, attributes the high number of abortions to lack of education on contraception. However, experts say that most of the abortions are due to the one child policy.

“[We are] fairly certain most of [the 13 million] are forced abortions,” says Colin Mason, who conducted field work in Guangdong and Guangxi Provinces in March this year for the nonprofit Virginia-based Population Research Institute. The two provinces are “models” in China, where the one child policy is strictly enforced and all birth quotas are met. Based on his experience in China, he said most people would have more than one child if they could.