Playing the dual roles of a player and a referee is one way to get filthy rich, and many corrupt Chinese officials have resorted to such tactics as they amassed staggering wealth when they tried to become artists, art collectors, and directors of arts associations, according to the mainland Chinese news website China Economic Weekly.

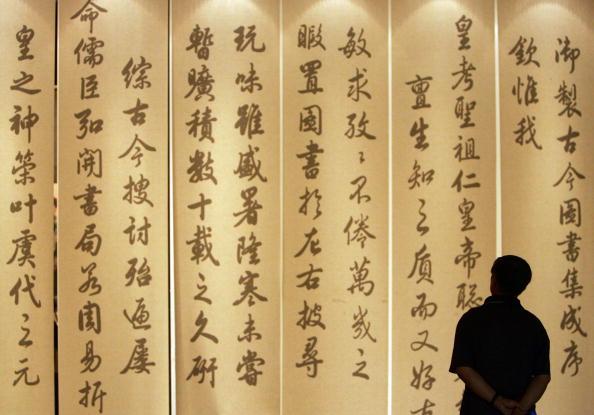

“Some officials cannot even write regular script well. They go ahead and write in semi-cursive script, and then have their writing framed and give it to another as a gift,” said Wang Qishan, the head of the anti-corruption watchdog, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), during a meeting on Jan. 13.

Wang was taking a jab at corrupt officials, singling them out for pretending to be calligraphy masters when they were not. Regular script and semi-cursive script are two different calligraphy writing styles, with the former considered to be more basic and easy to master.