Until late last year, Laura Gideon’s family lived in Porter Ranch on the outskirts of Los Angeles. “We didn’t ever want to leave,” Gideon told the Associated Press. It’s “a nice gated community.”

What uprooted them from one of LA’s wealthiest pockets? They became climate refugees when the nearby Aliso Canyon natural gas storage well sprang a nasty leak.

Clouds of gas have billowed from the faulty well, which lacked a subsurface shutoff valve, for three and a half months. After inhaling nonstop plumes of methane, benzene, and other toxic chemicals, local residents began to suffer nausea, vomiting, headaches, and nosebleeds. The disaster has also smacked local businesses hard and eroded real estate values.

Erin Brockovich, the activist and legal researcher made famous by an Academy-award winning film depicting her against-all-odds victory against another California utility, lives only 30 miles away. Now working with a law firm to help the locals file claims, she calls the Aliso Canyon leak a “BP oil spill, just on land”—because of its magnitude, duration, and climate impact.

And that’s why this incident imperils more than the people who live there and the bottom line of Southern California Gas Co., the local utility that ran the well.

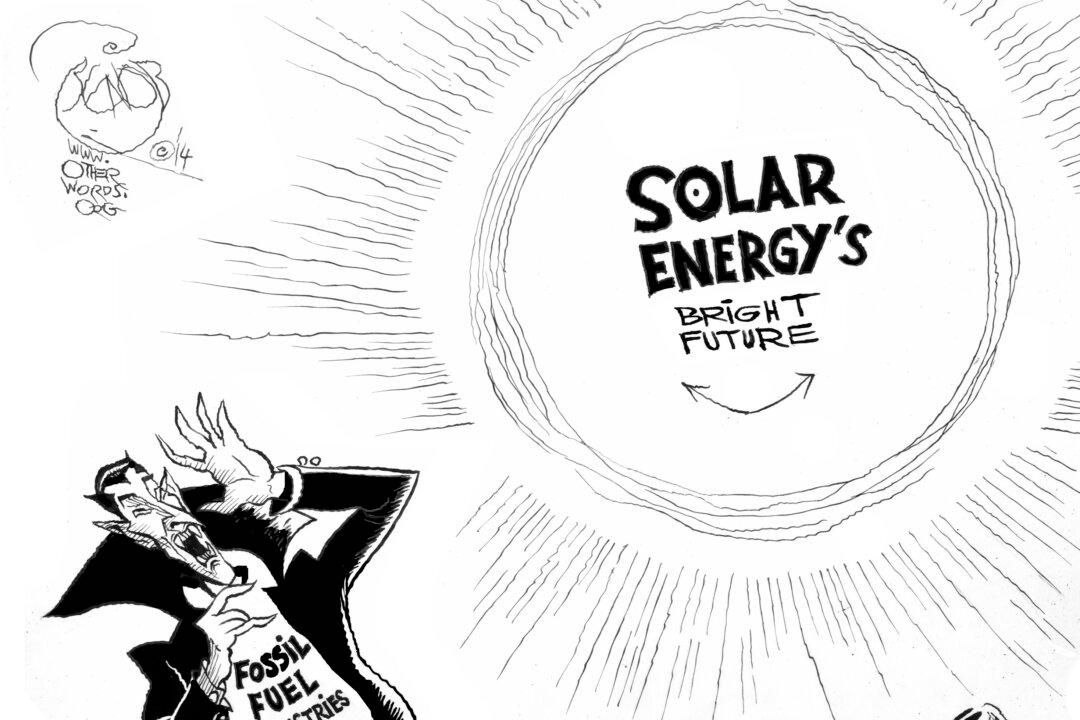

Just as the Gulf Coast disaster invigorated opposition to offshore oil drilling, the Porter Ranch debacle may sap the natural gas industry’s popularity. Above all, it’s exposing the fuel’s persistent reputation as “clean” and climate-friendly as a complete lie.

Environmentalists, backed by ample research, have struggled to debunk that narrative for years.

Although burning natural gas releases less carbon dioxide than coal or diesel, extracting and distributing it releases methane into the atmosphere. And so do storage accidents like this one.

And methane is between 86 and 105 times as powerful as CO₂ at disrupting the climate over a 20-year period. The now common practice of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, to obtain natural gas also pollutes waterways and squanders water—a big problem for parched California.