When 27 CSX tanker cars loaded with fracked North Dakota crude tumbled onto a West Virginia riverbank on President’s Day, the ensuing fireballs leveled a house and forced hundreds of people to flee amid a heavy snowstorm.

Even though 19 of the derailed cars—each carrying 30,000 gallons of oil—erupted into flames, nobody died in this particular disaster. But it may have fired a fatal shot into the argument that trains can “safely” haul crude across North America.

After most of these increasingly frequent accidents, critics urge the government to make operators use “safer” tanker cars. Yet the cars that went off the rails, exploded into flames, and then smoldered for days alongside the Kanawha River were the new-and-improved model.

Slower speeds are also billed as a way to increase oil train safety. Yet this one was chugging along at just 33 miles per hour in a 50-mph zone when it tumbled off-track between the aptly named towns of Boomer and Mount Carbon.

Given its quick growth, many Americans don’t get how big the oil-by-rail industry is or why they should worry about its risks. The number of crude carloads chugging across the nation rocketed from 9,500 in 2008 to 500,000 last year.

The advocacy group Oil Change International created an interactive map of oil train routes you can use to see if any run past your house. It looks like a giant spider web stretched from coast to coast.

Foes of oil-by-rail oppose the industry’s new reliance on what they call “bomb trains” because of how easily tanker cars can detonate when they go off the rails and how prone they are to doing that.

Some 1.4 million gallons of oil spilled in U.S. rail accidents in 2013—more in one year than over the previous four decades combined. A record 141 of these accidents occurred in 2014.

Proponents of building pipelines are trying to take advantage of conflagrations like that nightmarish scene in West Virginia. The best alternative to hauling oil by rail, they said, is to push it through stationary pipelines.

There are many problems with that argument. For one thing, ruptured pipelines spill more oil than wrecked tanker cars. Besides, the crude now traveling by rail is mainly drilled in North Dakota, where the local industry doesn’t appear eager to be boxed into pipeline routes.

Last year, a Koch Industries firm gave up after trying to build a pipeline that would transport North Dakota’s crude. So did a company called Enterprise Product Partners. Some observers said that given the brief lifespan of individual fracking wells, oil companies may prefer crude-by-rail’s flexibility.

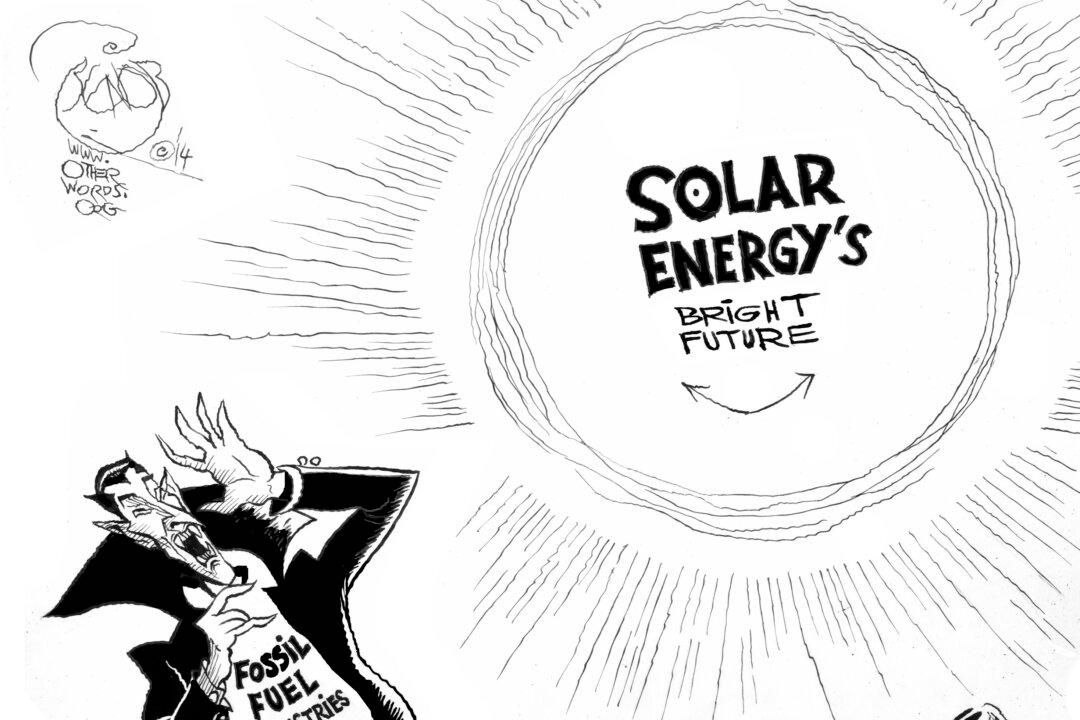

Building more pipelines, including the ill-fated Keystone XL, would just squander money as the nation’s energy outlook evolves. Many business leaders are embracing the ongoing transition away from oil, gas, and coal by betting on green energy.

Even Warren Buffett is starting to get on board. In addition to shedding its $3.7 billion stake in ExxonMobil, his Berkshire Hathaway holding company is pouring $30 billion into solar and wind power.

Meanwhile, the federal government is lumbering toward mandating the new tanker car design and leaving it up to individual states, counties, towns, and cities to muddle through their own oil-by-rail regulations.

What will it take to pull the brakes on this recklessness?

About 1,000 people live in Mount Carbon and Boomer, the largest towns directly impacted by the CSX accident. What if that train, ferrying 3.1 million gallons of oil, or another like it had derailed in a densely populated neighborhood? One of those fireballs could set Philadelphia, Baltimore, Chicago, New Orleans, or Seattle ablaze.

Surely that would be it for the crude-by-rail business. Do we have to wait until a big city erupts into a fossil-fueled inferno before this madness reaches the end of the line?

Emily Schwartz Greco is the managing editor of OtherWords, a non-profit national editorial service run by the Institute for Policy Studies. This article was originally published at OtherWords.