“Although not very large in terms of area size (about 2720.79 hectares from the original size between 4000-4700 hectares) [Tanjung Hantu and neighboring Segari Melintang Permanent Forest Reserves are] one of the few forests left in the locality that is still somewhat intact and unfortunately, under-researched,” Nurul Salmi, a professor with Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), told mongabay.com.

Two companies are involved in the project: Maegma Steel is building the steel coil mill, while Atigas Technology is constructing the liquified natural gas plant. To build the projects, officials have degazetted 60 hectares from the Tanjung Hantu Permanent Forest Reserve, but campaigners fear the actual impacts of the industrial projects, including roads and housing for workers, will spread across the two small forest reserves and the turtle beach.

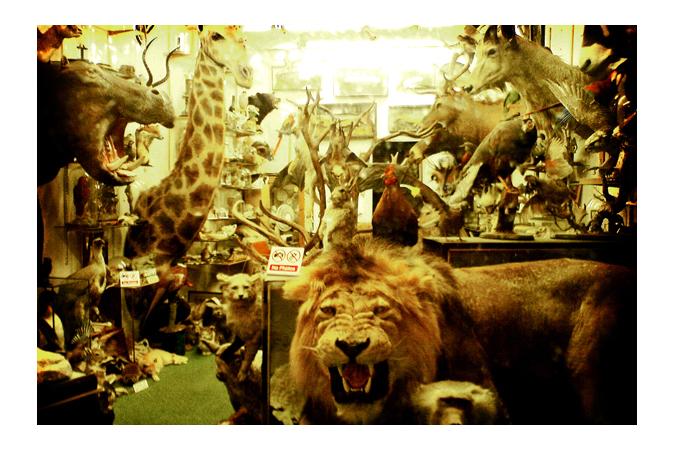

Both Tanjung Hantu and Segari Melintang are remnants of a vanishing forest type in Malaysia, according to Salmi. The reserves contain both coastal forest and hill forest and is home to two endangered dipterocarp tree species: Shorea glauca, currently listed as Endangered, and Shorea lumutensis, listed as Critically Endangered and only found in Malaysia. The forests are also home to charismatic, and threatened, mammals.

“Local villagers who frequent the forests have reported sightings of sun bear and black spotted leopard, which have been verified by evidence of tracks by the Department of Wildlife. However, studies must be carried out to find further evidence of these and other species,” said Salmi, who added, “perhaps there are other threatened and endangered species inhabiting the area.”

Tanjung Hantu is classified as an environmentally sensitive area under Malaysia’s National Physical Plan (NPP), which means that the area is only reserved for tourism development. However, this hasn’t stopped the Perak government from already degazetting a portion of the forest to make way for the natural gas plant and steel coil mill. Connected to the forest reserve is the seven-kilometer long Pasir Panjang beach, which is used by green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) for nesting. The species is currently listed as Endangered.

“Turtles are sensitive and timid creatures. They will avoid laying eggs in an area with bright lights or increased human activities. We predict that they will move away if these projects are built,” Meor Razak Meor Abdul Rahman, a field officer with the local environmental NGO, Sahabat Alam Malaysia (SAM), told the New Straits Times. “Given that Pasir Panjang is Perak’s only remaining turtle landing site, it is imperative that we do not lose this nesting ground to the threat of development.”

If the plans move ahead, Tanjung Hantu Permanent Forest Reserve will be one of a number of forest reserves that have been degazetted in the last few years in Perak. In July of last year, Bikam Permanent Forest Reserve was degazetted and clearcut for a palm oil plantation; the 400-hectare forest contained Malaysia’s last stands of another Critically Endangered tree, Dipterocarpus coriaceus. In all, 9,000 hectares of protected forest have been degazetted in Perak since 2009.

Last year, activists told mongabay.com that such degazettements of Permanent Forest Reserve have become commonplace since the election of Zambry Kadir as head of Perak state. In Malaysia, with a few exceptions, the heads of each state have sole power over degazetting protected forests. This means, protected forests can be lost without legislative approval, public notification, or even consulting with Malaysia’s Forestry Department.

“The chief minister can choose to degazette a [reserve] unilaterally, opting to disregard advice from the State Forestry Department, environmental NGOs, and even going against rulings made by Federal Government. The decision is taken at State Executive Council meetings, and proceedings of these meetings are treated confidentially,” Rahman told mongabay.com last year.

Malaysia has the world’s highest deforestation rate, according to a new Google-powered deforestation monitoring tool. Between 2000-2012, Malaysia lost 14.4 percent of its forests or 4.7 million hectares, an area larger than Denmark.

“Economic concerns are the priority with any government and generating revenue from natural resources available is the main agenda - however a compromise should be made between development and conservation,” said Salmi. “[The] government must be made to understand that if wise and long-term management and planning are implemented in these natural places they too could be revenue generators for the state for a long time to come.”

Activists point to the two forest reserves and Pasir Panjang as popular recreation spots that have major eco-tourism potential. In fact, the area is listed by the local government as a tourist zone. The region also supports a thriving fisheries industry which could be impacted by the industrial projects. Finally, the forests provide essential ecosystem services.

“These forests function as coastal protection from strong wind and waves, act as biofilter that protects water quality and habitats for a range of wildlife,” Salmi noted.

Activists have presented their 80,000-plus strong petition to local politicians, hoping that the projects will be relocated.

This article was originally published at the Mongabay.com.