What are the main elements of Lebanon’s presidential election process?

On April 23, Lebanon’s parliament met for the first session to elect a president, but failed to reach the necessary two-thirds majority to declare a winner. In subsequent rounds a contender can win by simple majority. The next round has been set for April 30. The term of the current president, Michel Suleiman, ends on May 25. There was no formal campaigning process for the post and contenders did not have to declare their candidacy beforehand.

Who are the major candidates and what are the likely scenarios for the election?

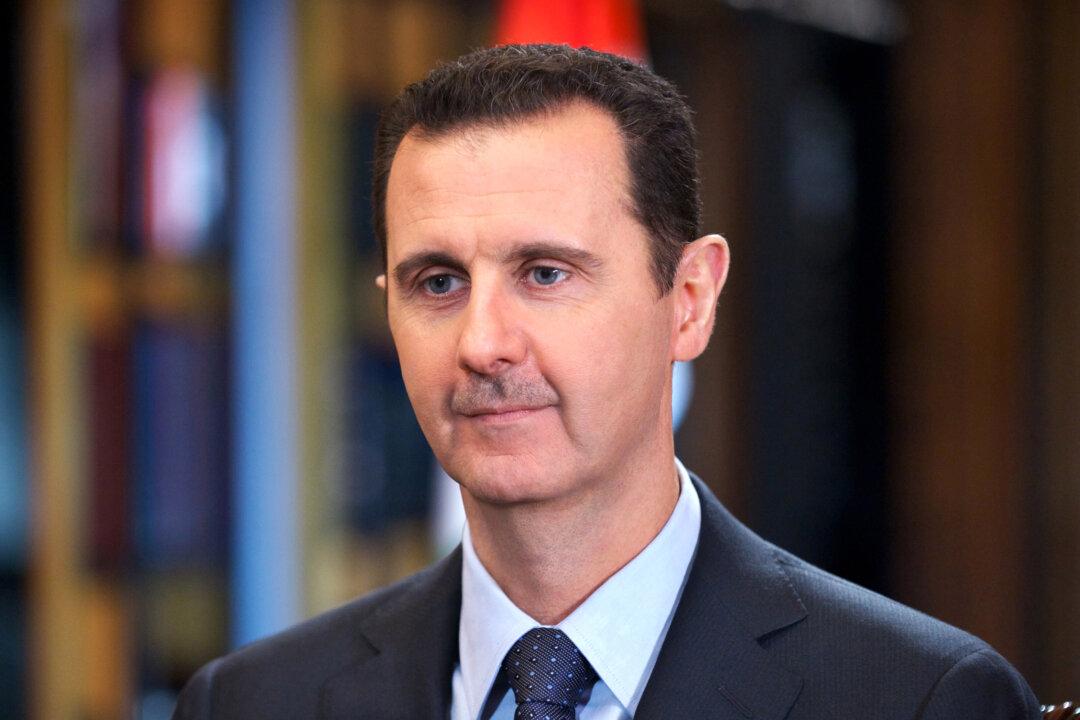

The two main coalitions in parliament are the March 14 coalition led by the Future Movement of Saad Hariri and the March 8 coalition dominated by Hezbollah. March 14 is close to Saudi Arabia and the West, and March 8 is close to the Assad regime and Iran. Neither coalition commands a simple majority, let alone a two-thirds majority. Currently the two coalitions do not agree on a consensus candidate. But there is much negotiating and politicking behind closed doors among the main parties, as well as in influential regional capitals such as Riyadh and Tehran, and possibly further afield in Paris and Washington.

Samir Geagea, leader of the Lebanese Forces Party, received the backing of the Future Movement of the March 14 coalition, and received 48 votes in the first round of voting, with 124 out of 128 members of parliament present. Although a presumed contender, the main Maronite leader in the March 8 coalition, Michel Aoun, did not declare his candidacy in the first round; the bloc, which would back him if he declared, cast blank ballots. In the second round of voting, Druze leader Walid Jumblatt, who commands a swing bloc of deputies, could be a deciding factor.

If none of the main contenders secures a majority and the sessions are postponed, it is possible that negotiations could move on to other politicians within the two main coalitions, such as former president (1982-88) Amin Gemayel in the March 14 camp or Suleiman Franjieh, grandson of former president (1970-76) Suleiman Franjieh, Sr., of the March 8 camp.

If this too fails, attention could turn to candidates outside the two main camps, such as Army Chief Gen. Jean Qahwaji, Governor of the Central Bank Riad Salameh, parliamentarian Robert Ghanem, former deputy Jean Obeid, or former minister of interior and civil society activist Ziad Baroud.

What is the significance of these elections?

Although Lebanon’s president has only limited executive powers, he stills plays an important national role. It is important for this election to go ahead successfully and on schedule in order for the country to keep its constitutional institutions alive in the face of increasingly destabilizing pressures from the Syrian war raging next door.

In addition to preserving the tenuous stability of the country in the face of the Syrian conflict, the president will need to keep relations between Sunni and Shi‘i blocs workable, maintain the health of the key political, security, and judicial institutions of the state, make progress in national dialogue talks among the main communities, and encourage progress in Lebanon’s emerging offshore gas sector.

Ideally, a new president should also play a leading role in proposing political, administrative, and socioeconomic reforms in a country that has been mired in internal division and deadlock for too long. His tools are limited: using the presidency as a bully pulpit, guiding the process of government formation, and influencing the agenda of the government and parliament.

What would be the next steps after a president is elected?

If a new president is elected, a new government would have to be formed. The current government, headed by Tammam Salam, is an inclusive national unity government that was formed two months ago after a 10-month hiatus. The formation of that government indicated a recognition of some common ground among the country’s factions and their regional backers, as well as the need for cooperation and consensus to preserve Lebanon’s fragile stability. There are hopes that this recognition will help the contending factions and their backers agree on a stabilizing way forward in the matter of the presidency.

The presidential elections should also be followed by parliamentary elections. Parliamentary elections scheduled for last year were cancelled, and the current parliament, controversially, extended its own mandate.

What are U.S. interests in this occasion?

The United States has a primary interest in preserving the stability of Lebanon, maintaining its political institutions, and encouraging national consensus in the face of escalating sectarian divisions and security threats stemming from Syria. The election of a new president is a Lebanese affair, but the United States should encourage all players to respect the country’s constitutional deadlines. It should stand by the new president once elected and encourage the formation of a new national unity government and the holding of fresh parliamentary elections. Most importantly, it should maintain and expand its support for the Lebanese armed forces that are playing a key security role at a time of great risk for this precarious republic.

Dr. Paul Salem is a vice president of the Middle East Institute leading an initiative on Arab transitions. He is the author of a number of books and reports on the Middle East, including “Broken Orders: The Causes and Consequences of the Arab Uprisings” (in Arabic, 2013); “Iraq’s Tangled Foreign Relations” (2013), “Libya’s Troubled Transition” (2012), “Can Lebanon Survive the Syrian Crisis?” (2012); and “The Arab State: Assisting or Obstructing Development” (2010). This article was originally published at the Middle East Institute.