The outlines of a US strategy to roll back ISIS, or the ‘Islamic State’ as it styles itself, in Iraq have become relatively clear, even if success is uncertain. But there is no clarity yet as to the strategy that might defeat ISIS in Syria. Elements of such a strategy might include use of US airpower against ISIS and Jubhat al Nusra in Syria, stepped up support to the non-jihadi opposition, and renewed emphasis on the replacement of Assad and the formation of an inclusive government including elements of the Syrian state and the non-jihadi opposition. The rise of ISIS also creates an opportunity to weave together a regional and international coalition to consolidate efforts and bring about a hasty end to the ISIS menace, which threatens all societies near and far.

In Iraq, the United States has a strategy. It used its airpower to stop ISIS’s advances and has largely contained it for the time being. It has started a partial rollback of ISIS, working with the Kurdish Peshmerga and Iraqi national forces to take back Mosul Dam and other positions. It is strengthening the Pershmerga and awaiting a new government in Baghdad that it hopes will include strong Sunni and Kurdish representation. If and when in place, the United States proposes to provide air and other forms of support to the national army and the peshmerga to gradually take back Iraqi territory seized by ISIS.

This is not an unrealistic strategy, but it does rely on a number of factors: success in forming an Iraqi national unity government; rebuilding some level of Sunni identification and trust in the central government and national army; and empowering Sunni leaders and groups that are willing to join in standing up to ISIS.

But even if success were eventually achieved over ISIS in Iraq, it would still have control of large swathes of Syria. Defeat in Iraq could cause ISIS to move resources and focus to take over more parts of Syria—Aleppo could be a particularly valuable target. Thus the Islamic State would persist as a regional and international threat, and from its haven in Syria it could bide its time to move into Iraq again when another opportunity arose.

Although there is still no clear US strategy for dealing with ISIS in Syria, US actions could soon have an impact there. The brutal killing of James Foley by ISIS in Syria has raised the stakes. Obama originally couched the actions against ISIS as limited to Iraq, and defensive in nature to protect Americans in Erbil and Baghdad and save stranded civilians on Mount Sinjar. After Foley’s killing, he described ISIS as a ‘cancer’ that must be eradicated, and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Martin Dempsey, said that defeating ISIS would require elimination of their havens in Syria.

US forces were active in Syria earlier this summer in a failed attempt to rescue Foley and other captives. The key question is whether the United States will use its airpower—both manned and unmanned— in Syria, as it has in Iraq, in the fight against ISIS. When asked about this, Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel said that all options were on the table. The public revulsion against Foley’s killing might also provide Obama with some political leeway for widening the scope of the air war against ISIS to include parts of Syria.

The use of US airpower could make an impact. It could significantly weaken both ISIS and Jubhat al Nusra, and provide an opportunity for the non-jihadi opposition to regain momentum. ISIS’s main foes in Syria are other rebel groups; its fights with the Assad regime have been limited. And so far the Assad regime has preferred to have radical jihadists on the other side with whom it cannot be asked to negotiate, and whose terrible acts shore up its support base. ISIS’s main proximate goal in Syria, like in Iraq, is to seize vulnerable areas that can be wrested away from central government control and that have an overwhelming Sunni majority. ISIS already controls Raqqa; it would seek to consolidate its control of Deir ez-Zor, Aleppo and Idlib provinces as well as Deraa in the South.

America’s only ‘friends’ in the Syrian arena are the fairly disempowered non-jihadi opposition including both Islamist and more secular groups, as well as main elements of the Syrian Kurdish armed opposition. The non-jihadi Arab opposition have been overshadowed by the radical jihadists of both ISIS and Jubhat al Nusra, but nevertheless they continue to hold ground and even make some progress in Idlib province and other parts of rebel held areas. This reality is partly the result of the meager support offered the non jihadi opposition in comparison to the support that the global and regional jihadi network could must for ISIS and Jubhat al Nusra.

If the US brought its airpower into play against ISIS and possibly Jubhat al Nusra, and in effect in support of the non-jihadi opposition, this could have multiple effects: it would help protect the Kurds and ’moderate' opposition from major ISIS or Nusra attempts to conquer their territories; it would directly empower these opposition groups against their radical jihadi foes; and it would give a great boost of morale to these groups, many of whom had perhaps rightly concluded that they had been abandoned.

It might also focus the attention of Washington—and its international and regional allies—that in order to roll back ISIS, they have to become much more serious and proactive about arming and training the non-jihadi Syrian opposition—something that has only been done piecemeal and ineffectively until now. Providing more support to the non-jihadi opposition would also encourage more Syrians to join its ranks.

Engaging US airpower against ISIS in Syria might help contain or even partially roll back ISIS there, and would help empower the non-radical opposition. But like in Iraq, a full strategy to eradicate ISIS in Syria would sooner or later have to include a new power-sharing deal in the capital. Here the recent example of Iraq might be instructive.

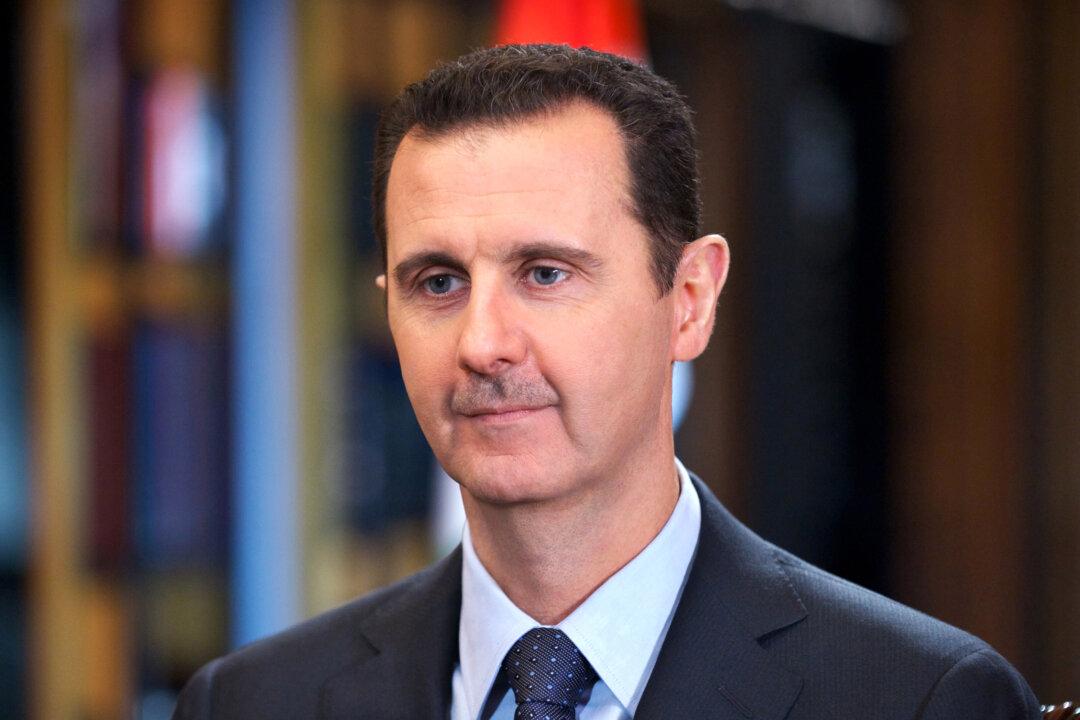

The United States made it clear to Baghdad—and indirectly to Tehran—that if US help was needed in fighting ISIS, it would have to be predicated on the removal of the ruler and the formation of a new power-sharing government. ISIS thrives on the hostility created by Assad’s persistence at the head of the Syrian state in Damascus.

The United States could make it clear to the Alawi community and other groups and communities that support the Assad regime—partly out of fear of the radical alternatives—as well as to Iran, that the it is not against the Syrian state and that it is a prime foe of ISIS and the radical groups. It could make it clear that if Assad is ’transitioned' out of power, as Maliki was in Iraq, and a new power-sharing government is put in place, the United States could then work with this reformed Syrian state—that would include members of the old regime and the non-jihadi opposition—not only to push back the dangerous radical fringe, but also to help bring back stability, security and eventually reconstruction to a reformed and inclusive Syria.

With the United States engaged, it could reassure fearful communities that making a historical bargain with the Sunni majority would not mean empowering the radical jihadi groups, but rather reinforcing the moderate middle.

The current crisis also creates a renewed opportunity for fresh international and regional diplomacy. The rise of the Islamic State is the biggest threat to regional and international security since September 11. Those events created an international and regional consensus on moving against al Qa'ida and their radical Taliban host state in Afghanistan. Now a proto-state even more radical than the Taliban has been built in the heart of the Middle East.

This development is of grave concern not only to the United States and Western Europe, but to Russia and China as well, and to all the states of the Middle East. It is a crisis that overshadows the crisis in Ukraine or tensions with China over trade or the South China Sea. It could be an opportunity for the US president to attempt a broad international and regional coalition against this terrorist threat.

The rise of ISIS demands a concerted approach. The outlines of a strategy to defeat it in Iraq have emerged; defeating it in Syria will be more complicated. The US is reprising a leadership role; it needs to act, but it also needs a more thought out strategy that includes Syria, and it needs to rally other states in the region and around the world to bring this dark chapter of horrific barbarity to a close.

Dr. Paul Salem is Vice President for Policy and Research at The Middle East Institute. He focuses on issues of political change, democratic transition, and conflict, with a regional emphasis on the countries of the Levant and Egypt. This article was republished with permission from the Middle East Institute. Read the original.