The live feeds have ended. See photos and videos here.

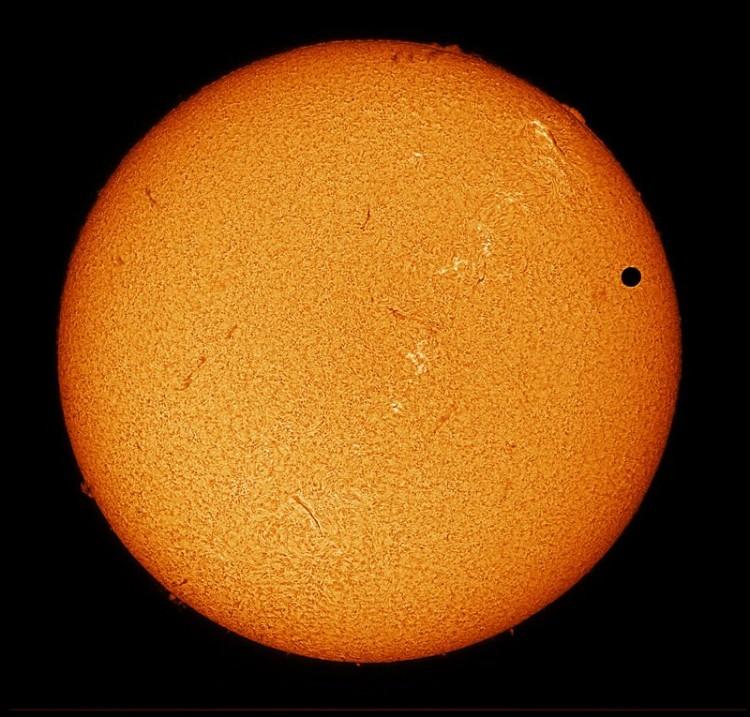

Last Transit of Venus for 105 Years

A once-in-a-lifetime event will take place on June 5/6 when Venus will be visible as a tiny black dot moving across the sun. The next Venus transit isn’t due until 2117.

Global visibility of the Venus transit. F. Espenak, GSFC/NASA

|Updated:

works with Cassie Ryan

science articles

China article

Author’s Selected Articles