The island of Hainan in the South China Sea is the largest of about 200 islands constituting the south-eastern Chinese province of the same name. On this island, a Critically Endangered primate struggles to survive in what’s left of its home.

Only about 30 Hainan gibbons (Nomascus hainanus) currently inhabit our world and all of them are confined to the 2,100-hectare Bawangling National Nature Reserve on the western part of Hainan Island. Endemic to this island, these gibbons primarily inhabited the lowland broadleaf and semi-deciduous monsoon forests that today are almost entirely deforested.

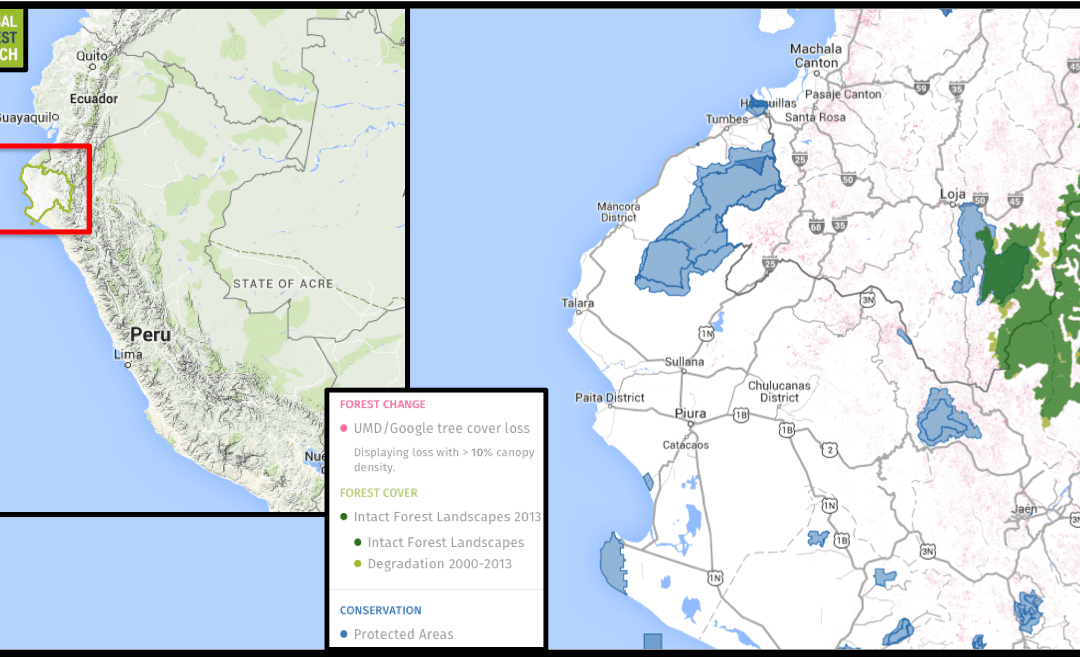

According to data from Global Forest Watch, Hainan province has lost an average of 15,084 hectares of forest every year from 2009 through 2012. In the 1960s, large parts of Hainan’s lowlands suffered major deforestation as forests were cleared for rubber plantations and commercial logging, leading to a dramatic drop in the Hainan gibbon population. By 1999, only 4 percent of the gibbon’s original habitat remained on the island.

Uncontrolled logging drove the gibbons to higher altitudes that lack the year-round supply of fresh fruit – the Hainan’s gibbon’s primary diet – and optimal shelter.

According to the IUCN, the population of Hainan gibbons dropped from more than 2,000 in the late 1950s and to fewer than 60 in 1993 due to habitat loss and hunting. A 2003 survey found just 13 gibbons while the latest estimates put that number somewhere near 30.

The gibbons’ preferred habitat is primary or old growth forests. However they will inhabit secondary forests—although they may have difficulty finding food and trees tall enough to accommodate their singing rituals.

One of the main reasons the IUCN classified the Hainan gibbons as Critically Endangered was because at least 80 percent of their population has been lost over the last 45 years, primarily due to hunting and habitat loss. A Greenpeace report stated the species is losing 200,000 square meters of habitat every day.

Hunting may also be to blame for the species’ decline, according to Dr. Samuel Turvey, Senior Research Fellow at the Zoological Society of London and an expert on past and present mammal extinctions.

“The gibbon population at Bawangling has held on in its isolated forest since at least 1980, but it hasn’t shown any substantial population growth or recovery during this period, and in fact has seemingly fluctuated for reasons we still don’t really understand - possibly partly because of hunting in the past,” he told mongabay.com. “It’s also been suggested that the mid-elevation forest that the gibbons are currently restricted to may not constitute optimal habitat for the species, which was once probably widespread at lower elevations which have now been totally deforested.”

“Without more suitable habitat for gibbons to disperse into and form new social groups, the population size will ultimately not be able to increase, so forest availability across the Bawangling landscape and beyond is really key to their survival,” Turvey said.

This drastic drop in available optimum habitat, researchers hypothesized in a 2008 study, may have led to reproductive adaptations in Hainan Gibbons, with monogamy falling out of favor among populations. Some of the remaining gibbons exhibit polygynous relationships, where small families consist of one breeding male, two mature females and their offspring. This mating structure seems to allow the gibbons to decrease the length of time between births – known as an interbirth interval. The Hainan gibbon’s two-year interval and gestation period are both shorter than that of most other gibbon species.

Between 1950 and 2003 the human population on Hainan exploded 330 percent, largely because of the open-door policy implemented by the Chinese government in the late 1980s. Construction of roads and towns accompanied the growing rubber and timber industries leading to habitat destruction and geographical isolation of the Hainan gibbons.

“The population is fully protected but is still at risk from so-called stochastic events which can pose a major threat to tiny isolated populations, so it’s still extremely threatened and vulnerable,” Turvey said. He said such a small population is highly susceptible to intrinsic threats like inbreeding depression and biased sex ratios, “which have previously not been fully appreciated as potential risk factors, and which can push the species towards extinction.”

Despite an economic boom on Hainan, average income is low compared to mainland China. With a female Hainan gibbon worth up to $300, according to a 2005 study published in the International Journal of Primatology, wildlife trafficking can be a lucrative venture. To make matters worse, gibbon bones are prized in traditional Chinese medicine, which led to many mass hunting sprees between 1960 and 1980, which resulted in the deaths of approximately 100 gibbons.

“The species experienced a precipitous decline in the twentieth century due to a combination of overhunting and rapid island-wide deforestation on Hainan,” Turvey said. “Today, the tiny remnant gibbon population is protected from hunting, but its population growth is limited by forest fragmentation and possibly ongoing human disturbance and available habitat quality.”

The Hainan gibbon is considered an umbrella species, which means its presence in an ecosystem indicates the habitat’s health and stability. If it were to go extinct, it would be the first gibbon species to be wiped out in the modern world. No other primate has gone extinct since the 1700s.

“As gibbons are important fruit dispersers, their loss from an ecosystem may well have impacts on forest regeneration, although the wider effects that their disappearance may have on Hainan’s forests remains very poorly understood,” Turvey said.

Conserving this species in its natural habitat in the wild is of utmost importance to its recovery and long-term survival, especially because captive breeding has consistently been unsuccessful. There are currently no captive Hainan gibbons in the world – the process of transferring them to captivity proved fatal and all previous attempts to breed them in captivity have failed.

But even for the world’s rarest primate, a ray of hope shines in the form of international and local experts working collaboratively to ensure the survival of the Hainan gibbon. Part II of this series will dig deeper into what’s being done to save them.

Citations:

- Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA Tree Cover Loss and Gain Area.” University of Maryland, Google, USGS, and NASA. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on Dec. 12, 2014. www.globalforestwatch.org.

- Zhou, J., Wei, F., Li, M., Lok, C. B. P., & Wang, D. (2008). Reproductive characters and mating behaviour of wild Nomascus hainanus. International Journal of Primatology, 29(4), 1037-1046.

- Zhou, J., Wei, F., Li, M., Lok, C. B. P., & Wang, D. (2008). Reproductive characters and mating behaviour of wild Nomascus hainanus. International Journal of Primatology, 29(4), 1037-1046.

This article was originally written and published by Apoorva Joshi, a correspondent for news.mongabay.com. For the original article and more information, please click HERE.