Many of the world’s protected areas may not be located in the areas that need them the most, according to a recently published study in the journal PLoS ONE. The study examined the effectiveness of Peru’s existing protected area system in holistically preserving the biodiversity in this megadiverse country, finding it inadequately protecting many of the country’s species.

The National System of State Protected Areas (SINANPE) protects a little over 15 percent of Peru’s territory, which includes biodiversity hotspots like the Tropical Andes and Tumbes-Choco-Magdalena, according to the study. Through this study, researchers identified and prioritized potential conservation areas using a novel combination of species distribution modeling, conservation planning and connectivity analysis. The set of 2,869 species they analyzed included mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, butterflies and plants. The study emphasized representativeness – an approach to conservation planning that means protected areas should ideally safeguard biodiversity as a whole and protect it from conditions that threaten its persistence. According to the study, as neither threats nor biodiversity are equally distributed on Earth, conservation planning ought to consider factors like endemism, threats, biodiversity richness and the size of protected areas. The authors say classical reserve selection criteria are usually based on opportunity, aesthetics or politics, and cannot always guarantee biodiversity conservation.

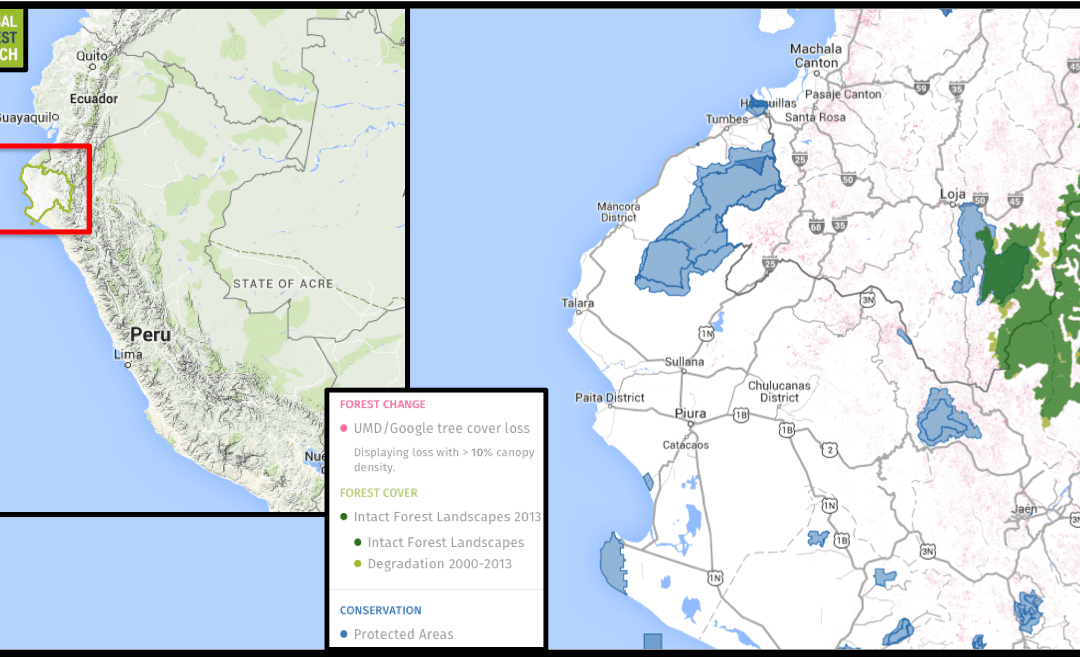

The study divides continental Peru into three geographical zones – the coastal area, the Andes and the Amazon ecosystem, which together account for 15.2 percent of Peru’s protected land and encompass about 100 reserves. Discounting marine reserves, the study considered 77 existing protected areas and identified conservation goals and gaps in these areas. The authors took 2,869 species into consideration, with birds the best represented and reptiles having the highest percentage of threatened species.

According to the study, the Amazonian humid forests of Loreto and Madre de Dios have the greatest species diversity followed by the Andes-Amazon transition in the central and northern Andean cordillera, and the coastal areas and the Altiplano in the southern Andes. Some iconic species found in these zones are the Sechuran fox (Lycalopex sechurae) that inhabits the coastal region, the Critically Endangered yellow-tailed woolly monkey (Oreonax flavicauda), Andean cóndor (Vultur gryphus) and spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus) found in the Andes, and the harpy eagle (Harpia harpyja) and jaguar (Panthera onca) of the Amazon.

Of the total number of species analyzed, a significant 29 percent are identified by the study as under-protected in the current national protected area system. Of the reptile species surveyed, the researchers found 50 percent were under-protected while amphibians had it slightly better at 30 percent. Birds and mammals, the researchers said, were better protected (22 percent and 20 percent respectively) primarily because their center for species richness was located within a relatively well-protected Amazonian ecosystem.

“I was shocked to see how many species might be under protected in Andes and the coastal region,” lead author Javier Fajardo told mongbay.com. Fajardo, a biologist originally from Spain but who now lives and works in Ecuador, said that like most others he had assumed most under-protected species would be found in the diverse Amazon habitat that gets global attention. While the very real conservation needs in the Amazon should not be disregarded, Fajardo said the situation in the coastal region was dire and starved of much-needed attention, which often determines the level of funding a particular area is allotted.

The study also showed that threatened species were in fact less protected than non-threatened species. All of Peru’s Critically Endangered species, 86 percent of its Endangered species and 62 percent of its Vulnerable species failed to achieve their conservation goals.

Of late, systematic approaches to conservation have helped create protected areas by proposing objective criteria for deciding where, why and how conservation resources and efforts should be directed to get maximum benefits and a more representative protection network. By designing their study to complement existing protected areas, Fajardo and his colleagues used site-selection algorithms in Peru for the first time to identify new potential strongholds for biodiversity that they proposed as conservation areas. They determined conservation goals for the species analyzed and evaluated whether current protected area systems were adept at achieving those goals. Researchers also identified severe conservation gaps and suggested a level of priority for the new proposed conservation areas that contribute towards creating a more representative protected area system.

The site-selection algorithms aim to help decision makers by proposing areas that maximize the achievement of conservation goals while minimizing the resources used. The study says that such systematic planning is particularly timely in biodiversity-rich tropical countries like Peru that face high deforestation rates and have fledgling reserve systems that may not add up to provide an efficient network.

An often overlooked step in conservation planning, the study says, is setting priorities within the list of proposed areas. Not all proposed conservation areas have the same characteristics, nor do they protect the same species or have the same urgency for protection. In such cases, analyzing priority becomes especially important because awarding a protected status to all proposed areas is not feasible. The researchers argue that a qualitative ranking assessment could help determine what to protect first.

Citations:

- Greenpeace, University of Maryland, World Resources Institute and Transparent World. 2014. Intact Forest Landscapes: update and degradation from 2000-2013. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on [date]. www.globalforestwatch.org

- Fajardo, J., Lessmann, J., Bonaccorso, E., Devenish, C., & Muñoz, J. (2014). Combined Use of Systematic Conservation Planning, Species Distribution Modelling, and Connectivity Analysis Reveals Severe Conservation Gaps in a Megadiverse Country (Peru). PloS one, 9(12), e114367.

- Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “UMD Tree Cover Loss and Gain Area.” University of Maryland and Google. Accessed through Global Forest Watch on Feb. 25, 2015. www.globalforestwatch.org.

- UNEP-WCMC, UNEP, and IUCN. “World Database on Protected Areas.” Accessed on [date]. www.protectedplanet.net.

This article was written by Apoorva Joshi, a correspondent writer for news.mongabay.com. This article is the first in a series of two, discussing the lack of protection for some areas of Peru. Link to the original article here, and to the second part of the original article here.