WASHINGTON—A ban on travel from West Africa might seem like a simple and smart response to the frightening Ebola outbreak there. It’s become a central demand of Republicans on Capitol Hill and some Democrats, and is popular with the public. But health experts are nearly unanimous in saying it’s a bad idea that could backfire.

The experts’ key objection is that a travel ban could prevent needed medical supplies, food and health care workers from reaching Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, the nations where the epidemic is at its worst. Without that aid, the deadly virus might spread to wider areas of Africa, making it even more of a threat to the U.S. and the world, experts say.

In addition, preventing people from the affected countries from traveling to the U.S. could be difficult to enforce and might generate counterproductive results, such as people lying about their travel history or attempting to evade screening.

The U.S. has not instituted a travel ban in response to a disease outbreak in recent history. The experts insist now is not the time to start, especially given that the disease is still extremely contained in the U.S. and the only people who have caught it here are two health care workers who cared for a sick patient who later died.

“If we know anything in global health it’s that you can’t wrap a whole region in cellophane and expect to keep out a rapidly moving infectious disease. It doesn’t work that way,” said Lawrence Gostin, a professor and global health expert at Georgetown University Law Center. “Ultimately people will flee one way or another, and the more infection there is and the more people there are, the more they flee and the more unsafe we are.”

Officials with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health voiced similar objections at a congressional hearing this past week. So did President Barack Obama after meeting with administration officials coordinating the response.

Obama said he didn’t have a “philosophical objection” to a travel ban but that he was told by experts that it would be less effective than the steps the administration has instituted, including temperature screening and monitoring at the five airports accounting for 94 percent of the arrivals from the three impacted nations. There are 100 to 150 arrivals daily to the U.S. from that region.

“Trying to seal off an entire region of the world — if that were even possible — could actually make the situation worse,” Obama said Saturday in his weekly radio and Internet address.

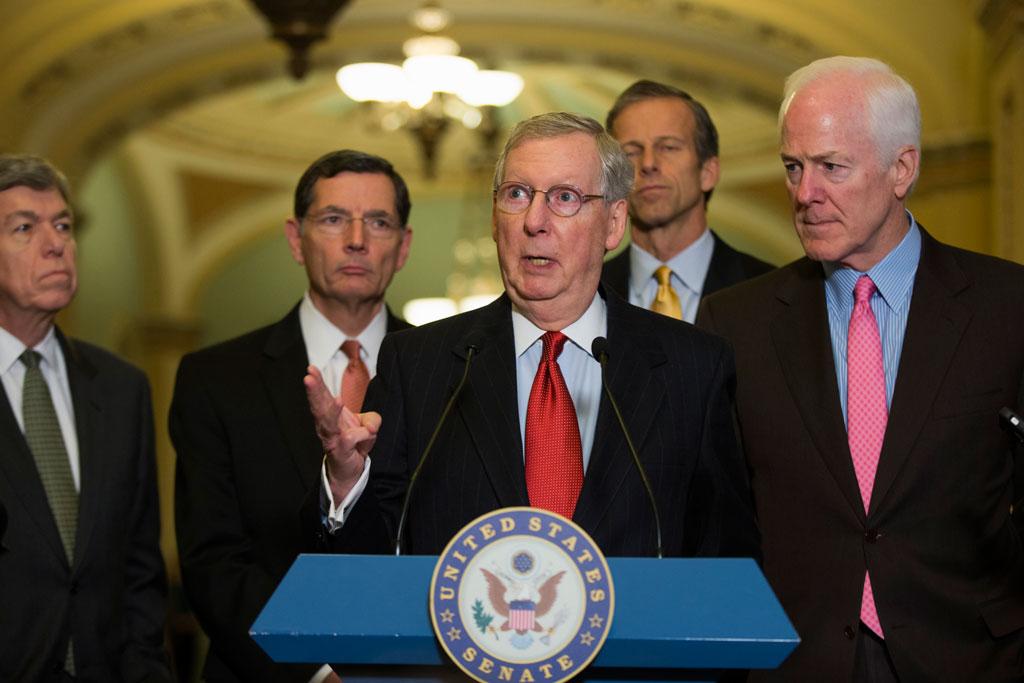

Still, with little more than two weeks from midterm elections and control of the Senate at stake, the administration is facing mounting pressure on Capitol Hill to impose travel restrictions. Numerous Republicans have demanded a ban, as have a handful of Democrats, including at least two endangered incumbent senators, Kay Hagan of North Carolina and Mark Pryor of Arkansas.

House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, also favors a travel ban, and his spokesman, Kevin Smith, said the speaker hasn’t ruled out bringing the House back into session to address the Ebola issue. Obama “has the authority to put a travel ban into effect right now,” Smith said.

Lawmakers have proposed banning all visitors from Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, or at least temporarily denying visas to nationals of those countries. They’ve suggested quarantining U.S. citizens arriving here from those nations for at least 21 days, Ebola’s incubation period, and limiting travel to West Africa to essential personnel and workers ferrying supplies.

Related steps that have been proposed by Pryor and others include strengthening existing quarantine centers, getting health officials to assist with screenings at airports and ensuring that information collected at airports on travelers from hot zones is shared with state officials.

Experts say some of those limited steps make sense but question the legality, ethics and effectiveness of large-scale quarantines. Although it would be theoretically possible to get supplies and medical personnel to West Africa even while shutting down commercial air travel, in practice it would turn into a logistical nightmare, they say. They cite expenses and difficulties in chartering private aircraft or enlisting the military’s assistance to transport thousands of personnel and huge amounts of supplies from around the world that is now moving freely on scheduled air travel.

Screening measures now in place allow arrivals from West Africa to be tracked; if those people go underground, attempt to enter via the Southern Border or by other means, it becomes that much harder to keep tabs on them.

Another difficulty arises because there are no direct flights to the U.S. from the impacted nations, raising the question of where to draw the line. Should flights from Paris, Amsterdam, London or Munich be banned if it turns out there is a passenger from Monrovia, Liberia, on them? Or should the other passengers just be screened? What if Ebola breaks out on European soil — should the travel ban be extended?

Among the travel ban skeptics is former President George W. Bush’s top health official, who coordinated the government’s response to bird flu in 2005 and 2006. At the time, it was feared that the H5N1 flu strain, capable of jumping from birds to humans, could become the catalyst for a global pandemic.

A travel ban “is intuitively attractive, and seems so simple,” said Mike Leavitt, who led the Health and Human Services Department from 2005-2009. “We studied it intensely in preparation for H5N1. I became persuaded that there are lots of problems with it.”

From The Associated Press. Associated Press writers Charles Babington, Ricardo Alonso-Zaldivar and Jim Kuhnhenn contributed to this report.