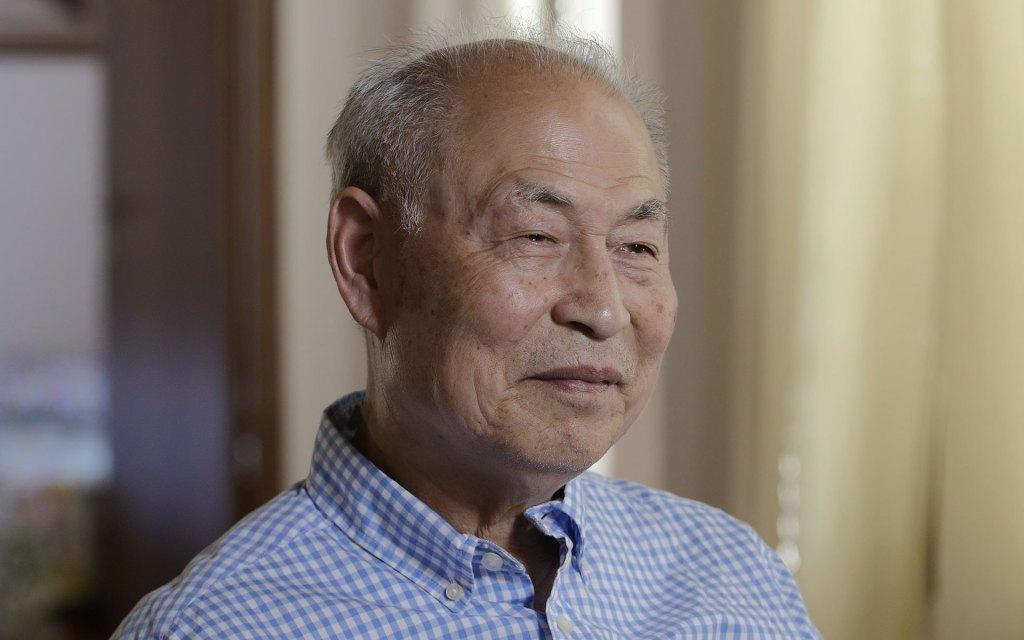

LOS ANGELES—With a filmmaker and playwright as prolific as Henry Jaglom, I have had the fortune to interview him and his leading lady and muse, Tanna Frederick, several times over the last few years. Each time, the exchange feels more like the reunion of friends than a professional meeting, engaging in intimate and truthful conversation—but then again, that is the endearing and alluring nature of Tanna and Henry, off camera or on.

Guiding our fluid conversation was the subject of their newly released film, Queen of the Lot, and the film’s themes of romance, the complex nature of actors, and their insatiable appetites for fame, affirmation, attention, and power.

Tanna Frederick plays Maggie Chase, action heroine. After her second DUI, Maggie dodges the paparazzi by fleeing to her manager’s house (Zack Norman). There she invites her bad-boy movie star boyfriend, Dov (Christopher Rydell), to join her and the entourage (Ron Vignone, Diane Salinger) before getting involved with his attentive and caring brother, writer Aaron Lambert (Noah Wyle), and the whole Lambert Hollywood power family (patriarch, Jack Heller).

Queen of the Lot is a laugh-out-loud Hollywood satire, and a sequel to Hollywood Dreams. Like Henry’s other films (Last Summer in the Hamptons, Festival in Cannes, and Venice/Venice), all explore the precarious relationship between the inner and outer life of performers, and the dubious intersection between “real life” and “the movies.”

The subjects of creativity and show biz are certainly matters about which Henry Jaglom can claim expertise, as he has worked as an actor, writer, editor, and director. And after decades in the business, the pioneering indie filmmaker has known and worked with legends—including Orson Wells, Jack Nicholson, Greta Scacchi, Dennis Hopper, and Vanessa Redgrave.

I met Tanna and Henry at their usual haunt in Santa Monica, joined by Ron Vignone, the film’s award-winning editor, who also plays Gio in Queen of the Lot.

We discussed the genesis of expression, Talmud intonation, and the paradoxical nature of some actors who feel most themselves or authentic when playing another character, and whether this is, therefore, their true authentic nature (very Talmudic).

Tanna, revealing a tender vulnerability, explained that she identified with her character Maggie, who says, “It’s not the Hollywood hype that scares me, it’s being in the kitchen and eating dinner that scares me. It’s the little things.”

The moments of her life that she recalls most vividly are the ones in which she is performing, reflects Tanna. The times she spent by herself she describes as feeling naked.

“The people I know feel more authentic on stage or in a role. They give themselves permission to express themselves through another medium … They know that character better than they know themselves,” explains Tanna, addressing the matter of actors always being “on.”

I feel like I’m floating in a strange void when I have no character to latch on to. I feel very uncomfortable with who I am,” says the woman who movie website New York Movie Guru lauds as a “sexy, charismatic, and immensely talented actress.”

Nonetheless, Tanna wonders if she might not suffer from “a defective personality trait.”

Redirecting the subject, she describes Henry as “a puppy trying to stay warm, like puppies through a store window.” His films are like “a whole bunch of people trying to stay warm emotionally, through words.”

Henry, touched by the analogy, acknowledged that films were a way to create a home in a world where he didn’t quite feel he belonged.

“Home is what my movies were to me—finding home in my mind, imagination, and dreams.”

“I’m allowed fiction now. It doesn’t all have to be autobiographical now because I satisfied the other thing, I have this in real life, I don’t need to create a home,” Henry says of personal journaling and of his films. “Now I have a home,” he says as he points to Tanna across the table.

“I wanted endless traces of myself—it was the only way I could understand life,” recounts Henry of his need to write in order to feel or ensure his existence. “I only stopped keeping a journal when I met you,” he says to Tanna. “I feel seen—I feel seen and known.”

“Now I’m looking outward,” asserts Henry, adding that his most recent projects reflect “what I have learned and seen around me. I have a great vehicle to express it—Tanna.”

When I inquired about what contributed to his evolution into such a comic realm, he surmised, “A reflection of my being happy.”

Guiding our fluid conversation was the subject of their newly released film, Queen of the Lot, and the film’s themes of romance, the complex nature of actors, and their insatiable appetites for fame, affirmation, attention, and power.

Tanna Frederick plays Maggie Chase, action heroine. After her second DUI, Maggie dodges the paparazzi by fleeing to her manager’s house (Zack Norman). There she invites her bad-boy movie star boyfriend, Dov (Christopher Rydell), to join her and the entourage (Ron Vignone, Diane Salinger) before getting involved with his attentive and caring brother, writer Aaron Lambert (Noah Wyle), and the whole Lambert Hollywood power family (patriarch, Jack Heller).

Queen of the Lot is a laugh-out-loud Hollywood satire, and a sequel to Hollywood Dreams. Like Henry’s other films (Last Summer in the Hamptons, Festival in Cannes, and Venice/Venice), all explore the precarious relationship between the inner and outer life of performers, and the dubious intersection between “real life” and “the movies.”

The subjects of creativity and show biz are certainly matters about which Henry Jaglom can claim expertise, as he has worked as an actor, writer, editor, and director. And after decades in the business, the pioneering indie filmmaker has known and worked with legends—including Orson Wells, Jack Nicholson, Greta Scacchi, Dennis Hopper, and Vanessa Redgrave.

I met Tanna and Henry at their usual haunt in Santa Monica, joined by Ron Vignone, the film’s award-winning editor, who also plays Gio in Queen of the Lot.

We discussed the genesis of expression, Talmud intonation, and the paradoxical nature of some actors who feel most themselves or authentic when playing another character, and whether this is, therefore, their true authentic nature (very Talmudic).

Tanna, revealing a tender vulnerability, explained that she identified with her character Maggie, who says, “It’s not the Hollywood hype that scares me, it’s being in the kitchen and eating dinner that scares me. It’s the little things.”

The moments of her life that she recalls most vividly are the ones in which she is performing, reflects Tanna. The times she spent by herself she describes as feeling naked.

“The people I know feel more authentic on stage or in a role. They give themselves permission to express themselves through another medium … They know that character better than they know themselves,” explains Tanna, addressing the matter of actors always being “on.”

I feel like I’m floating in a strange void when I have no character to latch on to. I feel very uncomfortable with who I am,” says the woman who movie website New York Movie Guru lauds as a “sexy, charismatic, and immensely talented actress.”

Nonetheless, Tanna wonders if she might not suffer from “a defective personality trait.”

Redirecting the subject, she describes Henry as “a puppy trying to stay warm, like puppies through a store window.” His films are like “a whole bunch of people trying to stay warm emotionally, through words.”

Henry, touched by the analogy, acknowledged that films were a way to create a home in a world where he didn’t quite feel he belonged.

“Home is what my movies were to me—finding home in my mind, imagination, and dreams.”

“I’m allowed fiction now. It doesn’t all have to be autobiographical now because I satisfied the other thing, I have this in real life, I don’t need to create a home,” Henry says of personal journaling and of his films. “Now I have a home,” he says as he points to Tanna across the table.

“I wanted endless traces of myself—it was the only way I could understand life,” recounts Henry of his need to write in order to feel or ensure his existence. “I only stopped keeping a journal when I met you,” he says to Tanna. “I feel seen—I feel seen and known.”

“Now I’m looking outward,” asserts Henry, adding that his most recent projects reflect “what I have learned and seen around me. I have a great vehicle to express it—Tanna.”

When I inquired about what contributed to his evolution into such a comic realm, he surmised, “A reflection of my being happy.”