HONG KONG—Two key leaders in international organ transplantation have for several years been involved in an undisclosed, cooperative relationship with Chinese transplantation centers, raising questions about whether the two Australian doctors have failed to make public a potential conflict of interest, according to recently uncovered documents.

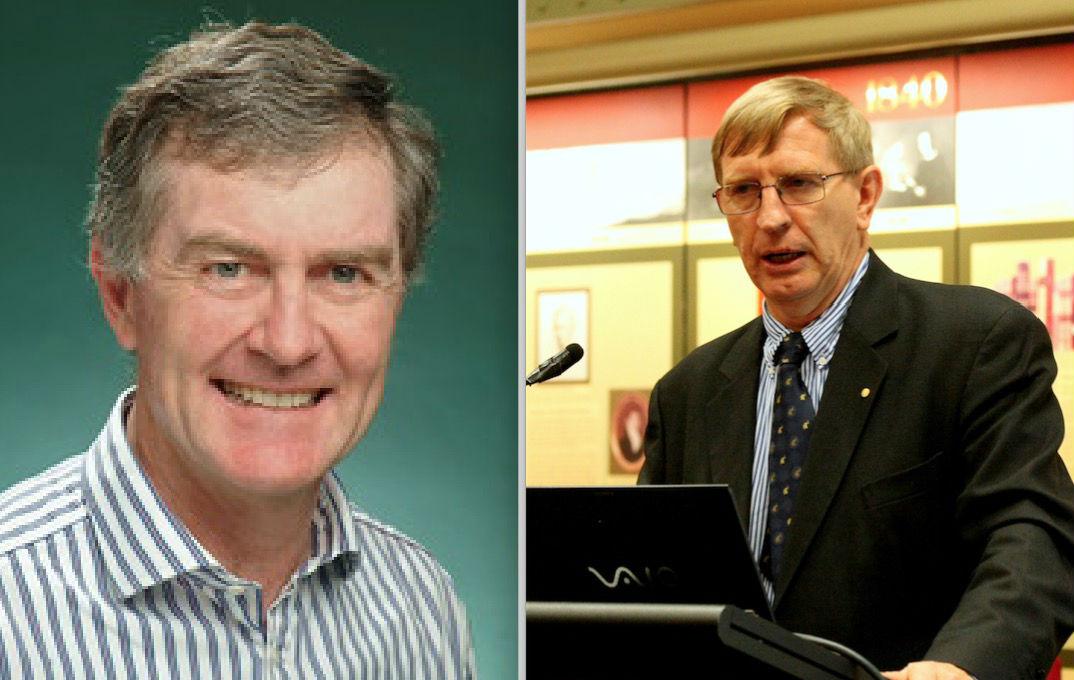

Dr. Jeremy Chapman and Dr. Philip O'Connell, both based at Westmead Hospital in Sydney, Australia, are respectively the former (2008–2010) and current (2014–present) presidents of The Transplantation Society (TTS), the international body representing the profession.

The interactions took place while the two played decisive roles in determining how the international transplantation community would respond to disturbing evidence that Chinese hospitals have been engaged in the large-scale killing of prisoners of conscience, whose organs are harvested for profit, according to independent researchers.

Chapman is also the chair of the scientific program for TTS’s major biennial conference, held this year in Hong Kong, starting on Aug. 18. The program has been criticized for including numerous doctors with histories of abusive practice in China, which critics say whitewashes China’s record.

Undisclosed Partnership

Since 2005, Westmead Hospital, a teaching hospital of Sydney Medical School, has had a relationship with The Third Xiangya Hospital, affiliated with Central South University in Changsha, Hunan, in central China. The earliest contact involved a visiting professorship for a key Westmead researcher; it continued in 2008 with a joint declaration of research standards. In 2012, Chapman and O'Connell attended a forum at The Second Xiangya Hospital, affiliated with the same Chinese university.

In November 2013, after attending a forum promoting China’s transplant system reforms, O'Connell and Chapman signed a “letter of intent” between Westmead and The Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, for both parties to “regularly conduct academic exchange conferences, engage in personnel exchange visits, and undertake advanced study and remote education in medical treatment, surgical demonstrations, and medical consultation,” according to a report on the hospital’s website.

In 2014, the relationship got closer, with O'Connell, then president of TTS, traveling to participate in a xenotransplantation conference on Oct. 16, followed by a delegation of 14 specialists from The Third Xiangya Hospital visiting Westmead from Oct. 27 to 30. Xenotransplantation refers to transplanting cells or tissues between different species, typically from animals to humans.

A meeting at Westmead included Chapman and Chen Fangping, president of Third Xiangya, signing another pact, this time a “supplementary agreement” to the 2013 letter of intent. It included “selecting a team of nurses and management staff to visit Westmead for advanced study,” and “other content” aimed at “deepening cooperation” between the parties. A photograph of Chapman shaking hands with Chen is highlighted in a report on the hospital website.

Among those who received the guests was a fellow Chinese researcher, Dr. Shounan Yi, whose presence provides a clue to the substance of the relationship between the two institutions.

Xenotransplantation

Since 2004, research on xenotransplantation has been restricted in Australia by a moratorium.

But Yi, a senior research fellow at Westmead and a protege of O'Connell, has been able by virtue of the relationship with Third Xiangya to perform research that is restricted in Australia.

The first contact between Yi Shounan and Third Xiangya took place in May 2005, when Yi took a position as a visiting professor there, according to a history of the hospital (he held the same post again in 2012). Wayne Hawthorne, an associate professor at Westmead, joined him a month later for three days of meetings.

Yi continued to research and publish on xenotransplantation over the years, including a number of joint publications with O'Connell and Hawthorne, as well as with Prof. Wang Wei, the resident xenotransplantation expert at Third Xiangya.

In 2011, during a stint there, Yi published research that it appears could not have been performed at the time in Australia due to ethics rules: the injection of pig islet cells into 22 patients with diabetes, a potentially lucrative treatment. The experimental procedure involves placing islet cells from the pancreases of pig fetuses into the host. The islets then produce insulin and regulate blood glucose.

“This is a gigantic market,” wrote Sina Finance, a major Chinese web portal, in a May 2016 story. “Even if there were 10,000 cases a year, that would mean a billion RMB in income.”

Yi is quoted in the article, commenting on recent research: “This makes us see hope for a breakthrough in the industrialization of xenotransplantation in China.”

But in Yi’s impressive list of publications, this particular study is nowhere to be found. (Yi also filed a patent application in 2010, with Wang of Third Xiangya, for a related medical technique.) Yi did not immediately respond to an email enquiring as to the reason for the omission.

The Westmead-Xiangya connection is not noted in any of O'Connell’s publications on xenotransplantation. Chapman has published four papers on transplantation issues in China (1, 2, 3, 4), some of which are broadly supportive of the official views of reform there, and the relationship with Xiangya is not disclosed.

Chapman and O'Connell did not immediately respond to an email with a series of questions about the connections between Westmead and Third Xiangya.

Conflict of Interest Concerns

The coincidence of the failure to disclose these relationships, involving potentially profitable research that could not be done in Australia, and the apathetic, sometimes hostile stance of TTS figures to evidence of widespread transplant abuse in China, has troubled observers.

The complex web of relationships, joint research projects, and grip-n-grins between Westmead and Third Xiangya doctors was pieced together by Arne Schwarz, an independent researcher based in Germany who provided the material in a dossier to a number of journalists.

Schwarz is responsible for the research behind pharmaceutical company Roche receiving a “Hall of Shame“ award in 2010 for its clinical transplant trials in China and has followed transplant abuse in China for many years.

He said that he began looking into potential conflicts of interest involving TTS leadership this June.

His curiosity was piqued by a dismissive remark made by Chapman following the publication of a nearly 700-page report on organ transplant abuse in China by independent researchers. The formidable report contained over 2,000 footnotes, over 90 percent of which are traceable back to hospital websites in China, and marshaled evidence indicating that the country’s transplant system operates at a scale far larger than previously understood.

The report now stands as the single largest collection of information on China’s transplant industry. Its researchers—David Kilgour, David Matas, and Ethan Gutmann—concluded that somewhere between 60,000 and 100,000 transplants are likely conducted in China annually; they believe that most of these organs come from practitioners of Falun Gong, a persecuted spiritual practice.

Chapman, however, in an interview with The Globe and Mail, dismissed the sources in the report as “all Falun Gong.”

When he read Chapman’s quote, “I couldn’t believe my eyes,” Schwarz said. He then became curious as to whether there was more than met the eye to Chapman’s relationship with China. So he began searching, and discovered the previously unknown set of relationships and interests.

The material was only discoverable through targeted Chinese-language queries; none of it had been reported previously in English, and it is not mentioned on Westmead’s website.

A number of Chapman’s colleagues were previously unaware of, and surprised by, the information. “That cooperation was never disclosed to The Transplantation Society’s Ethics Committee,” said Dr. Jacob Lavee, an outgoing member of the committee who is critical of what he considers the society’s lax stance toward transplant abuse in China.

“Present and past presidents of The Transplantation Society have significant influence on how the international transplantation community deals with the unethical transplantation system in China,” Schwarz wrote in an email.

He added: “If their judgment of the Chinese transplant practices is biased by vested interests in China, it can’t be trusted any longer.”

As Schwarz kept tugging on the ball of yarn, he found more and more that seemed questionable: the undisclosed meetings, promises of cooperation, joint research projects, and patents in potentially lucrative clinical procedures.

“Wow,” he wrote, recalling his thinking. “I understood why Chapman was so furious about the Kilgour-Gutmann-Matas report.”

In some ways, however, xenotransplantation research is only a sideshow to some of the more serious goings-on at Third Xiangya.

7 Transplants in a Day

Changsha is a relatively underdeveloped city in China, but it boasts three top grade hospitals—Xiangya, Second Xiangya, and Third Xiangya—all of them affiliated with Central South University.

Third Xiangya is a highly industrious transplant center.

In 2001—a year of “rapid development” in China’s organ transplant industry, according to Third Xiangya’s website—authorities invested 100 million RMB (about $15 million) in constructing a 150-bed transplant center there, which quickly became the best in the province.

Statistics show that the number of death row prisoners—the official source for transplantation organs—was in a decline while all this investment and development took place, indicating that organ sources should have been less, not more, abundant.

Third Xiangya quickly became a “national research base” for transplant technology and now performs large numbers of solid organ transplants (kidneys, heart, lung, liver), according to its website. According to research by the World Organization to Investigate the Persecution of Falun Gong, a nongovernmental network of researchers, the facility once performed seven transplants in a single day, when Huang Jiefu, China’s top transplant official, was visiting. This information has since been purged from the hospital’s website.

“Seven organ transplants at Third Xiangya Hospital on a special day when Huang Jiefu showed up for an anniversary ceremony!” an incredulous Schwarz declared. “How is this possible without a bank of still living donors?”

Ye Qifa, the deputy director of Third Xiangya and the executive director of China’s national organ procurement network, will be presenting at TTS’s Congress in Hong Kong on Aug. 18.

Alongside this, there are particular doctors at Xiangya who have engaged in questionable conduct, according to records online.

A Dubious Record

Perhaps the most prominent is Dr. Ming Yingzi, a transplant surgeon at Third Xiangya who is hailed as a rising star in the transplant profession by Chinese reports. According to a highly flattering 2014 biography of her on the hospital’s website, Ming’s team has performed around 1,000 solid organ transplants over the years. She “carries on her back a heavy icebox, fetching organs from everywhere,” the article says.

Given the realities of organ transplantation in China, almost all of these organs likely came from prisoners of conscience, who were killed for on-demand transplantation surgery, existing research indicates.

When she visited Taiwan in 2009, a large meeting of transplant recipients she had serviced was convened, where she was hailed as a “savior.” She’s personally performed 500 kidney transplants and 200 liver transplants, her profile says.

But she is also the subject of a lengthy prosecution in China for allegedly misappropriating 150,000 yuan ($22,000) paid by a patient for a kidney. Her lawyer in court acknowledged that she indeed received the money, that it was for a kidney, and that no receipt was produced, according to a local journalist. She says that she then gave the money to either the Red Cross, or a local organ procurement organization.

“She’s been changing her story,” said Jiang Jiasong, the lawyer for the plaintiff, in a telephone interview. “She’s never produced any evidence. ... I asked her which organ procurement organization she gave the money to, and she refused to answer.”

It is likely that none of this was clear to O‘Connell and Chapman. Ming’s biography on the Third Xiangya website provides what is almost certainly an apocryphal account of an interaction between the three. It says that when the two Australians were leaving Changsha in 2014, both of them gave her the “thumbs up” and made the remark, “Your achievements are astounding! We hope that you’ll become a leader in China’s new generation of organ transplant doctors!”

Westmead has been quiet about the relationship, brokered by Chapman and O'Connell, between it and Xiangya, and there is no mention of it on its website.

When asked for copies of the agreements between the institutions, and comment on the appropriateness of the relationship, Emma Spillett, senior corporate communications specialist at Westmead, part of the Western Sydney Local Health District, said “Thanks for your enquiry. We will get back to you ASAP.”

Three hours later she wrote back: “Western Sydney Local Health District will not be commenting on this matter.”