NEW YORK—Anna is a prototype of a Success Academy teacher—young, positive, attractive—exactly like about a dozen other teachers and employees from this charter school network I’ve met. Just like many others, she entered the network with ideals and enthusiasm. And just like many others, she left sobered on both accounts.

We sat down in a cozy Chelsea cafe and talked about how she joined, and later quit one of Success Academy’s schools. Even though her intent was simply to share her experience, Anna insisted her real name not be used so as not to antagonize her former employer. “I don’t want to burn any bridges,” she said.

Charter schools are run by private entities, but receive public funding on a per-pupil basis. Success Academy is the largest charter school network in the city, with 23 schools and 11,000 students.

Several years ago, while finishing her bachelor’s degree in liberal arts, Anna ran across an opportunity for a summer fellowship with Success Academy. She already had experience with tutoring and day care. “I was comfortable with kids, I have been doing that for a long time,” she said. “I felt like that was something that I’d be good at.”

She went through a few weeks’ application process and was among the 19 people accepted out of some 1,000 applicants. After three weeks of training in June she received five weeks of hands-on practice as an assistant teacher at a Success Academy summer school. Late in July she accepted a job offer as a second grade assistant teacher.

Long Hours

Anna spent the entire month of August going through professional development with her new work collective. “It’s a pretty short summer for teachers at this school,” she said. Indeed, if picked to do the summer school instruction, a Success Academy teacher would end up with about one week of summer holiday.

The school year started at the end of August, several days earlier than at traditional public schools. Anna said she had to “hit the ground running.” It almost felt like the deck was stacked up against her.

“I was very on board over the summer. I was a believer,” she said. But fairly early in the school year her perception changed.

She was placed in a rather new school where a large part of the staff was just as new to the job as she was. This included the management. She ended up in the largest second grade class with 33 students. It was also the class with the most difficult students, Anna said. And to make things worse, she felt like her personality didn’t match well with the lead teacher she was assigned to.

The lead teacher possessed natural authority and had a very strong grip of the class. But Anna didn’t feel like she was given a chance to develop her leadership. “She never really gave me an authority in the classroom,” Anna said. “So when she would leave, it would be chaos.”

Success Academy schools usually have classes of about 30 students, equivalent to what would be considered an overcrowded public school class. To balance it off, each class has two teachers, one lead and one assistant. After one year the assistant teacher can become the lead.

Business Culture

The Success Academy company culture is similar to a Wall Street business environment. Although a nonprofit, the network was set up by two hedge fund managers, John Petry of Sessa Capital, and Joel Greenblatt of Gotham Funds.

“The Success model includes teachers whose intensity is a mix of Internet startup and trading desk, and a vast amount of training, maniacal attention to data, and replicable processes,” said Daniel S. Loeb, manager of hedge fund Third Point LLC, at a fundraiser for Success Academy last year, according to Bloomberg. Loeb is board chair of Success Academy.

The teachers’ lounge is called “teachers workroom” at Success schools. “You’re never lounging at Success Academy,” Anna said, laughing uncontrollably. “You’re always working.”

The problem was there was no space to vent grievances after a stressful day, definitely not the teachers workroom. “A lot of the time you had to be careful,” Anna said. If you couldn’t help yourself, chances were an email would come saying, “Someone heard you being negative in the teachers workroom. That’s not OK.”

And it didn’t stop with emails. Two weeks into the school year one of the most experienced teachers was fired over an argument with the principal. “She was universally acknowledged to be the best teacher,” Anna said. “The entire school was almost in a mutiny.” A week later the teacher was hired back. “It was a very, very weird thing to happen,” Anna said.

With such a tone being set, teachers invented “whisper sessions,” as Anna called them, sharing their problems in low voices among themselves.

Another teacher was fired later that year after her assistant teacher quit. “She was also a very good teacher,” Anna said. “It was a disagreement with the leadership.”

Apart from firing, a lot of teachers were reshuffled from class to class during the year, making it difficult to create a stable environment for the students. “You are changing classroom dynamics every time you make a staff change,” Anna said.

Out of 14 people from the fellowship that got jobs at Success along with Anna, only four still work there.

Burnout

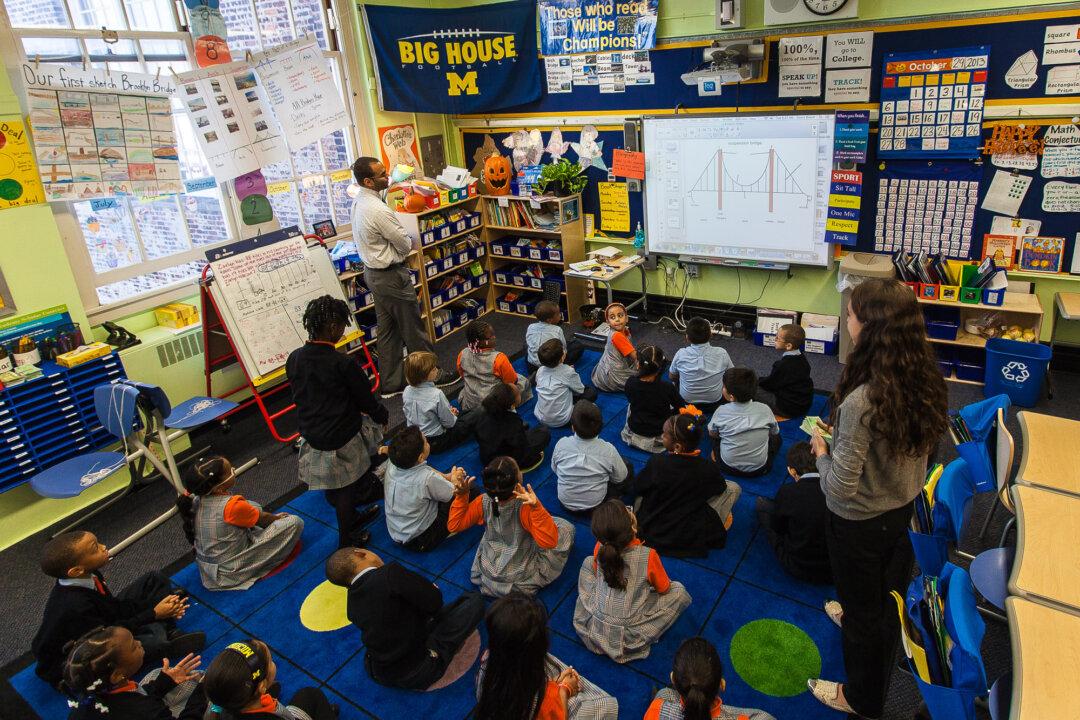

Success Academy boasts that its students and teachers work extremely hard. “We can’t have a teacher who’s not working at 110 percent, when we’re asking the kids to get 110 percent,” said Abigail Johnson, principal of the Success Academy Williamsburg during an Oct. 29, 2013, school tour.

The school day is 7:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. for children, translating to 6:30 a.m. to 6 p.m. for teachers. The workload is intense too. Meetings cut into lesson preparation time and the lessons themselves are fast-paced, planned down to the minute, sometimes to the second.

“I felt exhausted,” Anna said. After coming home, sometimes she would just eat something and collapse on her bed at 9 p.m. Soon enough, it started to take a toll on her health. “I was sick all the time,” she said. Having a class of children sneezing in her mouth, as she put it, didn’t help either.

But taking a day off is almost a taboo. Success Academy boasts of maximizing the efficient use of teachers’ time. Even a principal would chip in to help with reading instruction, and substitute teachers do not exist. Anna said she would feel guilty about staying home, as it would mean one of the other already overwhelmed assistant teachers would have to take over her class.

She ended up in such a position herself many times, when she would learn at 7 a.m. she was to teach someone else’s class by herself. Thus, calling in sick was like a betrayal to the collective, and even to the management. “There was often a feeling like ‘Oh, you’re sick? Are you able to stand up? Why aren’t you there?’” Anna said.

Test Prep

Success Academy shows some of the best results in the state on standardized tests. Over 80 percent of students pass math, and over 50 percent pass English, compared to a 30 percent city average.

Since the state mandated testing starts at third grade, Anna was spared the direct pressure. Yet, once January hit, the whole school was permeated with a push for high scores. “How can we support third-, fourth-graders” would become a common theme of the principal’s weekly memos. Test prep would take over the classes for the next four to five months, until May, when the tests were over. Teachers from lower grades were expected to help with the test prep too.

The focus on the teachers from tested grades would sometimes turn ridiculous, such as when they would have special food ordered for them. If you had friends among them, you could get yourself a burrito, Anna said laughing.

Even after the school day ended at 4:30 p.m., weaker students would stay to get more test tutoring.

Routines

Success Academy is known for drilling children in a set of routines, to give students tight structure and help teachers manage the classes. For example, when the teacher gives out a task, the students will wait for the teacher to flick their fingers before starting to work.

Other routines include repeating what the teacher said in unison, or repeating specific chants. Anna said the goal is to create a “camp-like group fun mentality.”

Anna said the routines work “to varying degrees,” depending on the teacher. “I saw classrooms where the routines work almost perfectly, like 95 percent of the time. I saw other classrooms where they would work for a bit, but only if the class wasn’t too riled up. In my case, I would say the routines worked for me about 60 percent of the time,” she said.

In the first weeks of the school year, teachers were expected to focus solely on the routines. If one student fails to follow, the whole class would repeat the task.

“That’s a great idea in theory,” Anna said. “Sometimes in practice, when you’re getting 33 kids to take a pencil out again, and again, and again, that’s a waste of time.”

Later in the year children were expected to follow the routines flawlessly. But that was not always the case. “At the end of the day these are kids, they’re not machines,” Anna said.

Sometimes she would be put in impossible positions, being criticized both for not repeating routines until correct, and being late for the next class due to repeating routines.

She thinks the overreliance on the routines had a lot to do with a lack of experience. “When you’re starting out, you hold on to the routine for your dear life,” she said laughing, conspicuously talking about herself.

Anna noted a lot of the problems at the school were probably connected to over half of the staff being new to their jobs. “I’m sure everyone is better now than they were,” she said.

Based on the experiences of her friends from the fellowship at other schools in the network, if she was assigned to a different school, she may have never quit, Anna said. “There were schools that were really working in our network when I was there, and there were schools that weren’t working.”