NEW YORK CITY—While most performing arts companies struggle financially, relying on government or corporate grants to operate, Shen Yun Performing Arts has beaten the odds, running a self-sustaining business model, allowing it to grow from one performing arts company to eight now touring the world.

The company was started by practitioners of the Falun Gong spiritual discipline with a mission to revive traditional Chinese culture. Through its art, Shen Yun also raises awareness about the persecution Falun Gong faces in communist China.

Yet this artistic and financial success has drawn repeated attacks by The New York Times—at least nine articles directed against the company in less than five months, including several this week.

This time, The New York Times cast the company in a negative light for keeping cash reserves. The article also attempted to explain away Shen Yun’s success by saying some Falun Gong practitioners have volunteered time or money to host and promote Shen Yun shows.

In its opening paragraphs, The New York Times goes as far as to suggest that Shen Yun “may have” obtained some money illegally, but then leaves the allegation unsubstantiated.

The New York Times reporters also made false statements in the article and concealed from readers that they were made aware of the inaccuracies before publication, The Epoch Times has learned.

“It is also true that we have built, on our own, the fastest-growing performing arts company in American history.

“What [The New York Times] gets completely wrong is why, and, in many regards, how we did it.”

Shen Yun has become a major cultural phenomenon, putting on a new classical Chinese dance production every year that showcases “China before communism,” as its tagline reads. Its dance troupes, each accompanied by an orchestra, perform for a total global audience of about a million people each year.

Countering Religious Persecution

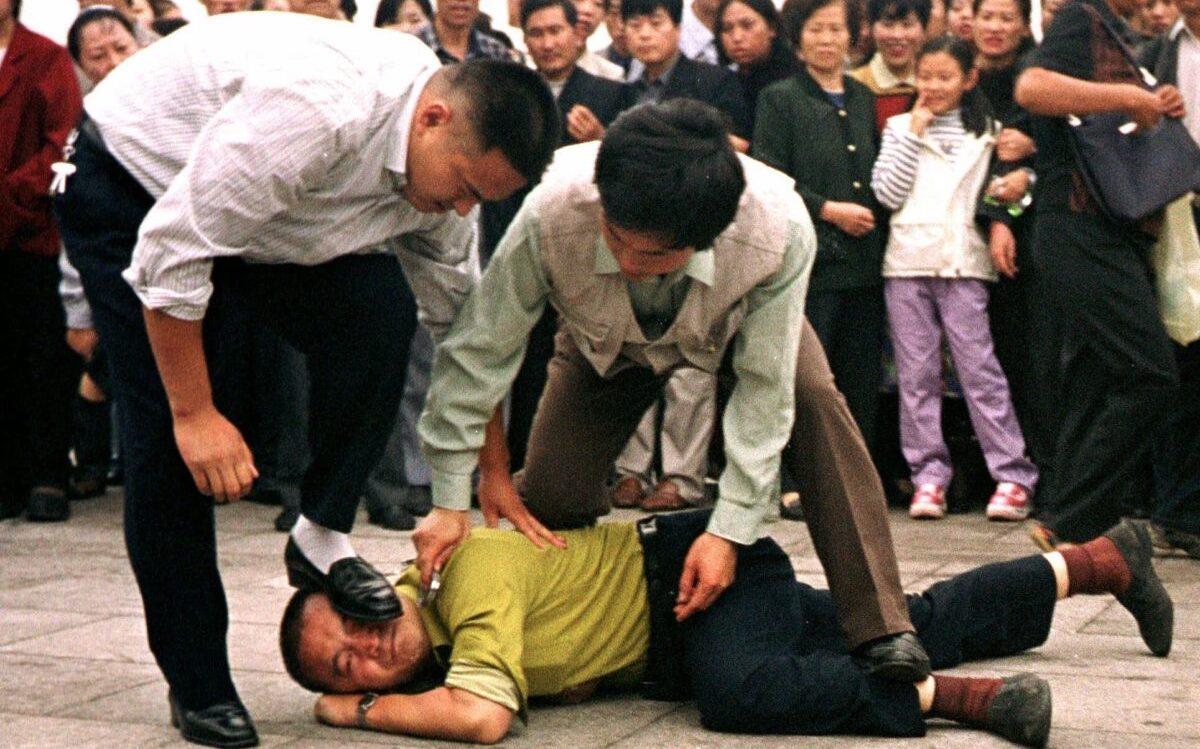

Falun Gong, a spiritual discipline consisting of meditative exercises and teachings based on the principles of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance, became immensely popular in China during the 1990s. By 1999, between 70 million and 100 million people had taken up the practice, according to official estimates at the time. That same year, the CCP’s paramount leader, Jiang Zemin, accused Falun Gong of competing with the official communist ideology and launched a repression campaign. The regime set about rounding up and sending millions of practitioners to prisons and labor camps, often to die of torture or have their organs extracted for the Chinese regime’s then-burgeoning transplant industry.A significant proportion of Falun Gong practitioners inside China and around the world have been active in raising awareness about the persecution, often on behalf of family members imprisoned or facing abuse in China. Virtually all such work has been carried out on a voluntary basis.

“Falun Gong practitioners have tried to organize and find creative and non-violent ways to not only help their family and believers in China, but also to help Chinese people and those around the world to stop participating in the persecution and to see through the CCP’s harmful and false propaganda,” said the Falun Dafa Information Center (FDIC), a nonprofit monitoring the persecution of Falun Gong.

“This stems from a deeply held belief—common in many faiths—that good deeds are rewarded and bad deeds—especially the violent persecution and killing of innocent people—are punished, if not in this life, then after death,” the group stated in a press release.

Despite the massive scale of the persecution in China, and the grassroots efforts to expose it, news media in America were slow to pick up on the issue, with some exceptions, such as Ian Johnson’s series of articles on the topic for The Wall Street Journal that earned him the Pulitzer Prize in 2001.

At the New York Times, rather than reporting on a major human rights story, they took the opposite approach, according to an FDIC analysis released earlier this year. In the early years, the paper parroted the CCP’s anti-Falun Gong propaganda. After that, it virtually ignored the issue, even as evidence of the abuses mounted.

In recent years, the paper has turned to outright attacking the Falun Gong diaspora in the United States, particularly Shen Yun.

The FDIC questioned the timing of the latest series of articles—which coincide with whistleblower reports that the CCP has launched a new campaign to “eliminate” Falun Gong overseas, “including via media reports by outlets without visible ties to the regime,” the FDIC said in a Dec. 30 release.

“The Times’ caricature of Shen Yun passes over every bit of the real story—one of blood, sweat, and tears of brave men and women fleeing persecution in China,” the Shen Yun statement said.

Grassroots Efforts

Many Falun Gong practitioners perceive Shen Yun’s success as a breakthrough in raising awareness about the ongoing persecution, Gail Rachlin told The Epoch Times.Rachlin is a New York-based real estate broker and former executive at American Airlines, FedEx, and Hilton. She was among the earliest Falun Gong volunteers raising awareness among the American public.

“When Shen Yun came, it was like, ‘Oh my goodness, this is an incredible opportunity to tell people more about who we are,’” she said.

With her background in hosting corporate events, Rachlin immediately offered to help host the show in New York.

“Shen Yun is our best way to express what’s going on. It’s our freedom expressed,” she said.

The show received rave reviews and was praised for its uplifting message, high level of artistry, and impeccable production. Each season, Shen Yun includes one or two dance pieces depicting the persecution. Its masters of ceremonies also share with the audience that this is the reason Shen Yun cannot perform in China.

Typically, a group of Falun Gong practitioners living in an area will invite Shen Yun, usually through a local nonprofit, to perform in the top theater in their locale.

Ticket sales proceeds are used to cover the expenses of the hosting organization and the contracted performance fee paid to Shen Yun.

In some cases, local hosts promoted the show on their own dime and then reimbursed themselves once the ticket sales kicked in.

The New York Times used one such case in Indiana during the 2017/2018 season to falsely claim that the shows didn’t make enough money for the hosts to recoup their initial expenses and that they used government grants to do so years later.

The president of the hosting organization, the Indiana Falun Dafa Association, however, had informed the New York Times reporters in an emailed statement that this was false, prior to the article’s publication.

“I would really appreciate it if you can provide the ‘records’ you are using to make these false statements,” he wrote, never receiving a response.

The shows were in fact very successful, did make enough money to cover expenses the same season, and no government grant money was involved, he explained to The Epoch Times, offering a 2018 bank statement from the nonprofit as proof.

The New York Times reporters didn’t include any portion of his statement in their article.

The reporters claimed that Falun Gong practitioners help with Shen Yun shows because they view it with “religious fervor” and as a means to save people from a “coming apocalypse.”

The Epoch Times spoke to about half a dozen Falun Gong practitioners who previously helped host Shen Yun shows. They universally dismissed any talk of apocalypse.

Instead, they identified three reasons for supporting the show. They shared passion for traditional Chinese culture and believe its revival, after being decimated by the CCP, is a worthy cause.

They also view the show as spiritually uplifting for the audience.

“It brings hope and helps people to find out the softest spot in their heart, the kindness in their heart,” said Xing Chen, who has been hosting Shen Yun shows in San Antonio for the past four years.

“It benefits society, benefits humanity, and that’s a very meaningful thing to do so I’m proud I can be part of it.”

Lastly, they considered the show a potent avenue for raising awareness about the repression in China.

“That’s the reason we’re supporting it,” Rachlin said. “Not because of some ‘doomsday.’”

Portraying Falun Gong as a doomsday belief is an old propaganda trope used by the CCP in the early years of the persecution. It has been repeatedly debunked.

“It is … disturbing to see that some of the themes in the article mirror, with shocking similarity, the CCP’s propaganda against Shen Yun and Falun Gong,” Shen Yun said in its statement.

“Twenty-five years ago, such narratives were formulated by Beijing to strip us of our freedoms, dehumanize and silence us, and turn people against us in order to facilitate a nationwide campaign of violence and killing,” the company said.

“The reemergence of these exact same themes on the pages of the Times should foster grave concern within the Times organization, and certainly among its readers.”

The New York Times reporters further alleged that one Shen Yun staff member used all her savings to pay for equipment and some luxury items for Shen Yun and its staff and then died of cancer, lacking funds to cover treatment.

The company said the staffer “was urged by Shen Yun colleagues to curb her unnecessary and sometimes lavish spending” and her “failure to care for her health was also the subject of concern from those around her.”

“After repeatedly refusing care, a Shen Yun staff member finally demanded she be taken to the hospital and took her there themselves,” it said.

Running a Performing Arts Nonprofit

The New York Times tries to portray Shen Yun as making money through donations, grants, and cost savings. But a review of its financials reveals a much different picture—less than 18 percent of its revenue came from grants and contributions in 2023.It owes its financial success overwhelmingly to strong ticket sales, the documents show.

“Like many start-ups, we relied on personal heroics at the beginning, including an all-volunteer team working mostly nights and weekends to build our dream … As we continued to grow, we increased salaries and services for our staff,” the company said.

It describes the costs to run its operations as a “sizable responsibility given the all-inclusive approach we offer our people.”

The company said it offers many staff members free room and board.

“We also help fund the Fei Tian schools that share our campus, which provide full scholarships for all students which include room and board and are valued at about $50,000 a year.”

As the company expanded and its shows garnered popularity, its revenue also increased, reaching about $50 million in 2023.

The New York Times questioned why Shen Yun saves its money in a bank, without spending or investing it. But the publication didn’t explain why it would be nefarious for the company to keep cash reserves. It didn’t allege the cash reserves were being misused in any way.

“We want to ensure a high level of financial preparedness,” Shen Yun said in its statement.

“In fact, we were able to keep all of our people through the COVID-19 pandemic, even while not performing for a year and a half and have every intention of being able to do that again if needed.”

The company emphasized that it needs to manage its finances with a long-term perspective.

“[The New York] Times’ fixation upon our company cash reserves seems misplaced, perhaps stemming partially from an ignorance of what it takes to actually run an organization like Shen Yun,” the company said.

“Unlike a vast majority of performing arts companies in the world, we have no corporate sponsors, no regular government support, and no active member donation program. We survive the old-fashioned way: by the value our product brings to consumers.”

The article accused Shen Yun of “skirting rules” to obtain a bigger chunk of COVID-19 pandemic relief funding for the two seasons that government-imposed lockdowns and restrictions prevented it from performing.

Shen Yun called the accusations “very misleading.”

Portraying Shen Yun as primarily a money-making machine seemed irrational to Rachlin.

“If you want to make money, there’s a lot of other ways to make money,” she noted.

Shen Yun launched in 2006 facing daunting odds. It had no name recognition, no home stage, no government support, and no corporate donors or philanthropic patrons lined up.

The company also adopted an extremely complex production strategy, with custom-made costumes, an animated backdrop, and a live orchestra. In addition, it chose to create brand new choreography, costumes, backdrop designs, and musical compositions every season. And it started on New York’s oversaturated performing arts scene.

Chen found it bizarre that The New York Times would cast a shadow on Shen Yun because people like her volunteered for it.

“People now are just living for money, huh?” she told The Epoch Times. “We have our spiritual side, and we pursue something above and beyond the daily life, something intangible.”

The New York Times repeatedly tried to insinuate, without evidence, that Falun Gong founder Mr. Li Hongzhi has financially benefited from Shen Yun.

Mr. Li, who is usually addressed by Falun Gong practitioners as Shifu—meaning Teacher or Master—introduced Falun Gong to the public in 1992 through a series of seminars across China. Mr. Li’s main teachings were then published as a book, “Zhuan Falun.” The book became a national best-seller in China, before being banned by the CCP, which confiscated the books and even held public burnings.

Mr. Li has on occasion given talks at conferences hosted by Falun Gong practitioners, mainly in North America. Several collections of those have been published as books as well.

“All Falun Gong books and instructional videos are also available online for free in over 40 languages and all Falun Gong conferences are free of charge to attend. It is clear that financial gain has never been his motivation.”