China is in the grips of infighting among Communist Party leaders that threatens to spill into public struggles unseen in a generation.

The increasingly bitter divide between contending factions reached new levels this week when a key ally to one of the Party’s most aggressive cadres was taken back to Beijing by high-ranking officials for investigation.

That cadre, Politburo member Bo Xilai, has launched an aggressive campaign against organized crime in parallel with a campaign to reignite Maoist communist zeal.

Such campaigns, normally only launched by the Party leader, are widely seen as an effort to reverse Bo’s declining political fortunes and secure a spot on the Standing Committee of the Politburo, the nine-member elite organ that controls the Chinese Communist Party. At the 18th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party later this year, a new head of the CCP will be selected and the membership of the Standing Committee reshuffled.

But Bo’s effort looks deeply undermined after his right-hand man, Wang Lijun, 52, came under investigation for corruption by the central authorities and is widely rumored to be selling out Bo, his old boss, in efforts to save himself.

Click this tag to read The Epoch Times’ collection of articles on the Chinese Regime in Crisis. Intra-CCP politics are a challenge to make sense of, even for veteran China watchers. Here we attempt to provide readers with the necessary context to understand the situation.

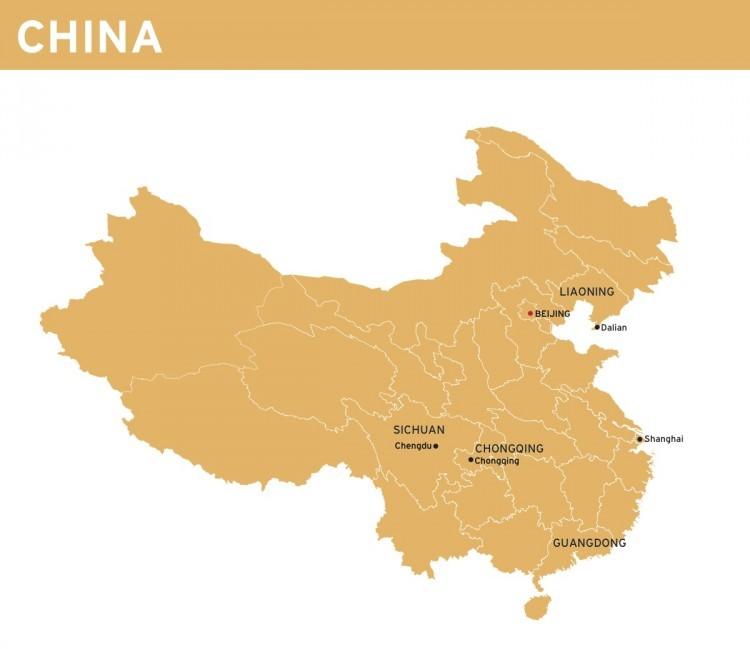

Wang Lijun was first of seven deputy mayors and top cop at the Chongqing Public Security Bureau until Feb. 2 when he was relieved of duties with the police and demoted to the seventh ranked deputy mayor responsible for education. The demotion now appears connected to his being investigated for corruption by a higher-positioned political rival.

But Wang’s fall took a dramatic turn when he fled Chongqing to Chengdu City about 170 miles away and hid out in the U.S. Consulate as some 70 police cars from Chongqing surrounded the building.

Wang later surrendered to authorities from Beijing rather than the police, raising rumors that his split from Bo had put his life in jeopardy.