During the early years of the Han Dynasty (漢朝) (206 B.C.–A.D. 220), there was much turmoil on China’s northern border. The frequent incursions by the nomadic Xiongnu people were one of the greatest concerns of the Han emperors.

When Emperor Wu of Han ascended the throne in 141 B.C., he abandoned the defensive policies of his predecessors and launched many counter-attacks. His strong armies defeated the Xiongnu many times.

During this period, there were attempts to negotiate peace, however, each side would often detain the other’s envoys.

Although conflicts gradually diminished, the fate of the envoys remained in doubt.

Hope for Peace

In 100 B.C., the Xiongnu king, or Chanyu, made a gesture of peace toward the Han by releasing the imperial Chinese messengers his people had detained.

Emperor Wu planned to reciprocate this peacemaking effort by returning the Xiongnu detainees, along with valuable gifts, as recognition of the Chanyu’s good will.

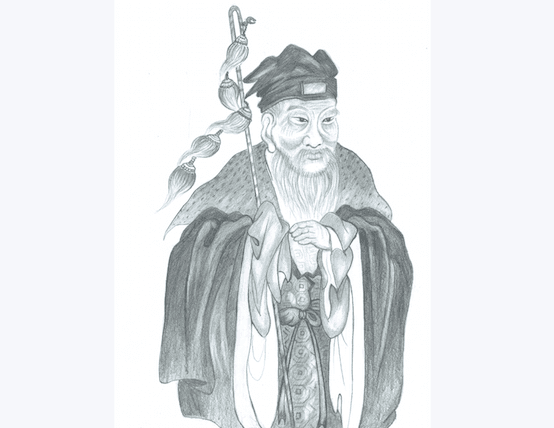

The emperor chose Su Wu (苏武) (140–60 B.C.), a high-ranking palace official,to undertake this diplomatic mission.

Su Wu’s father had been an official and, because of his father’s status, Su Wu became a palace attendant at a very young age. However, he advanced in rank in his own right, eventually becoming an official.

Su Wu led the delegation of over 100 men from the capital, Chang'an (長安) to repatriate the Xiongnu envoys. No one expected that this mission would take 19 years.

A Thwarted Mission

Su Wu’s delegation arrived at the Xiongnu stronghold and completed the detainee delivery. However, the gifts from Han were taken as a sign of weakness and the Chanyu, unimpressed by the imperial diplomats, became more arrogant instead.

Just before the group was to return to Chang'an, Su Wu and his entire staff were detained. The Chanyu was furious to discover that Su Wu’s assistant, Zhang Sheng, had been conspiring with others against him. The Chanyu pressed Su Wu to surrender.

Although he knew nothing of the plot, Su Wu knew he would be implicated. Determining that he had failed his mission and his emperor, Su Wu tried to commit suicide, stabbing himself to show his loyalty to the state.

Alarmed, Zhang Sheng and others intervened and saved his life. The Chanyu, impressed by such sincere loyalty, monitored Su Wu’s recovery.

When Su Wu recovered, the Chanyu tried again to persuade him to surrender, offering riches and a high-ranking position. However, Su Wu remained faithful to the Han emperor and his commands.

A Life in Exile

The Chanyu then tried various ways to get Su Wu to surrender, including death threats, promises of wealth and power, and torture.

Once, the Chanyu had Su Wu locked in a dark cellar for several days without food and water. In the bitter cold, Su Wu ate snow to quench his thirst and ate the leather from his clothing to relieve his hunger. Still, he did not betray his emperor and surrender.

Realizing the envoy’s steadfast loyalty, the Chanyu exiled Su Wu to a desolate location by the North Sea (Lake Baikal in modern-day Russia), to live as a lone shepherd. He told Su Wu that he would be allowed to return to the Han “when your rams give milk.”

Su Wu was unmoved. During the day, he herded the flock of rams by the lake. At night, he stayed in a tent with no company. To survive, Su Wu raided the burrows of field mice and ate plant roots.

However, whether awake or sleeping, Su Wu kept the Han imperial staff by his side, sometimes using it as a shepherd’s rod. As time passed, the decorative hairs on the staff fell away until only the bare rod was left.

During Su Wu’s exile, the Chanyu again attempted to gain the envoy’s surrender. He sent Li Ling, a former Han official who had surrendered to the Xiongnu,to try to convince Su Wu that serving the Chanyu was in his best interest.

Su Wu chastised Li Ling, saying, “My father, my brothers, and I were without merit or virtue. All we have was bestowed upon us by the emperor.

“A subject serves his lord as a filial son serves his father. If a son is to die for the sake of his father, he has no regrets. His faith does not waver. Even in the face of harsh punishment, he has no fear.”

Li Ling felt deeply ashamed upon hearing Su Wu’s words. He later sent Su Wu a gift of several dozen sheep and cattle, wishing to reduce his hardship.

Repatriation and Honor

Following the death of Emperor Wu in 87 B.C., a new emperor ascended the throne. Later, the Xiongnu also saw a new Changyu take power. In 81 B.C., seeking peace with the Han, the new Changyu released Su Wu along with nine remaining members of his delegation, the others having surrendered or died.

After 19 years in exile, Su Wu finally returned to Chang'an, now a frail, old man with white hair and beard, who still held firmly the bare rod of his imperial staff. All who saw him were moved to tears.

In order to reward Su Wu’s faithfulness and loyalty, the emperor bestowed upon him many valuable gifts and lands. However, Su Wu chose to live a simple life, giving his possessions away to others. He died around the age of 80.

The story of “Su Wu herding sheep” has been passed on from generation to generation and Chinese history regards Su Wu as the exemplar of an official’s great and unshakeable faith and loyalty.

Through temptation and torment, Su Wu remained unmoved, maintaining his integrity even in the face of death. He not only gained the admiration of the Chinese people, but the respect of the Xiongnu as well.